Unless you're out there taking photos with a camera the size of a pickup truck, chances are that the pictures you take of your subject are much smaller than the real thing.

Magnification in photography determines the relationship between the true size of your subject and the photos that we take to remember them. Fully-grown adults are now the size of Barbie dolls. Expansive landscapes are reduced to a form that fits right in our pockets. The world becomes something small enough to carry away with us, remembered forever.

What Is an Image in Photography?

The ratio between the true size of the subject and the image of them that hits our camera's sensor boils down to something called magnification. But what is magnification? Before we can tackle this one, we first need to establish a solid definition for the word "image."

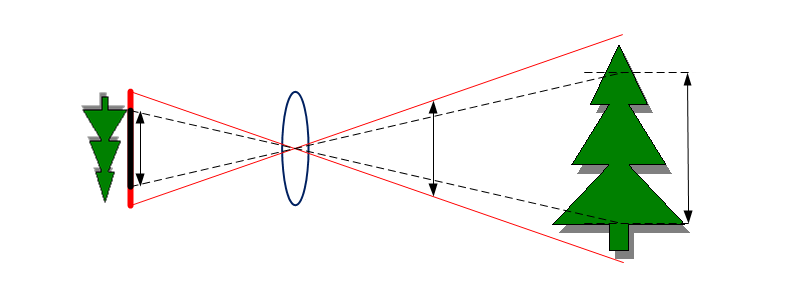

An image is more than just the final photo. In order to get the photo "inside" of the camera, the light that the subject and the surrounding area conveys must be organized and cast against the plane of photography, a slide of film or a digital camera sensor.

As weird as it is to think about, this "part" of the photo is just as real as the actual picture that we can hold or save to our computer. Like a movie coming out of an old-school projector, this representation of the subject exists in its own right. It's just as important as the final photo itself.

What Is Magnification?

To put it simply, magnification in photography is the size of the image projected against the sensor compared to the size of the subject in reality. A photo of a face boasting a one-to-one ratio of magnification would require more than a printer that can reproduce the photo at the same scale as the original face. Instead, what you would need is a camera sensor that is at least as large as the face itself.

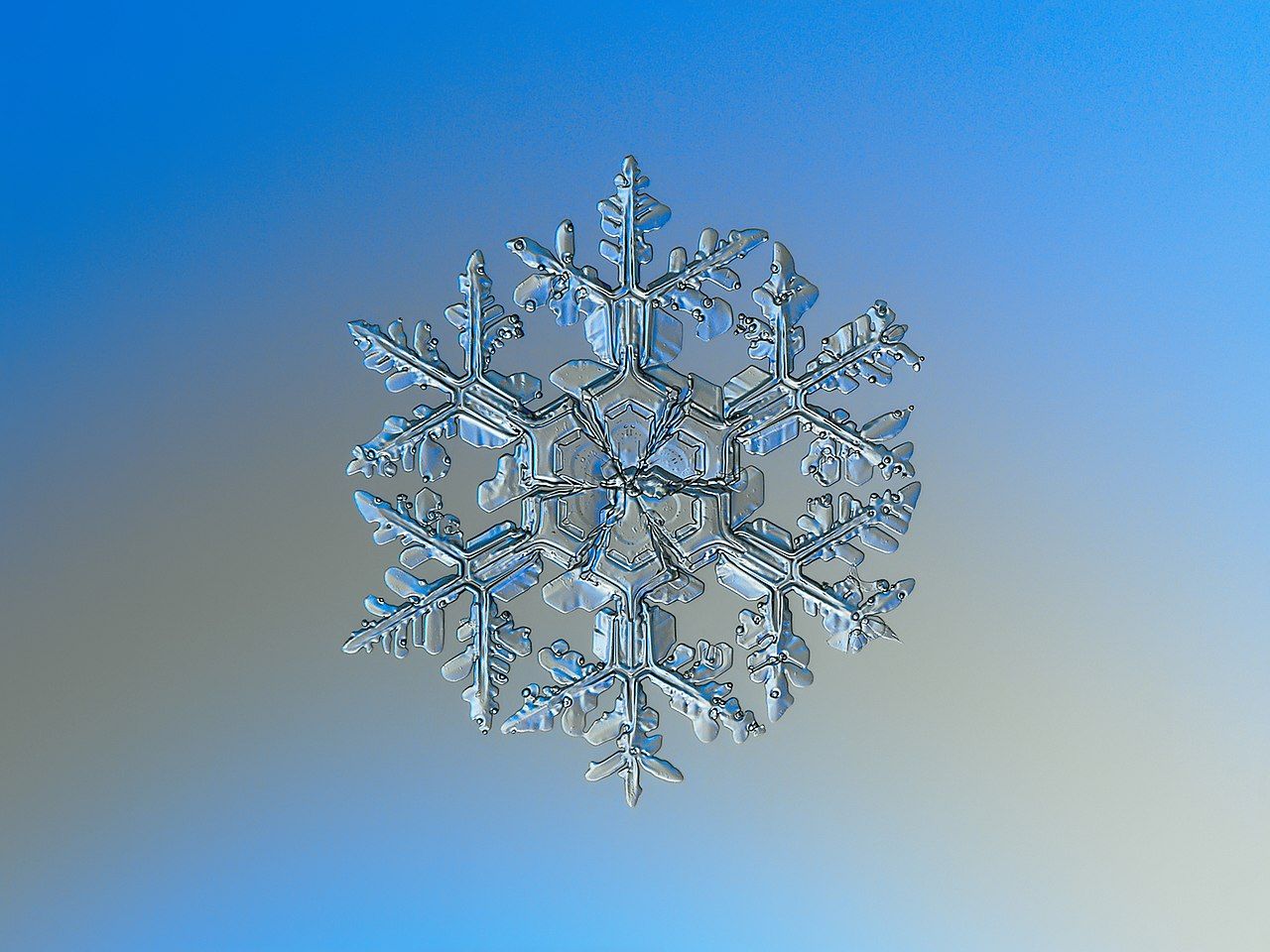

For most, equipment at this level delivers diminishing returns; we mention this example only to illustrate the concept at its core. Unless you're shooting insects exclusively, the images that you capture will usually end up being much smaller than the subject as it stands in real life.

There are many configurations that can yield what amounts to essentially the same result. Using an average, mid-length lens at a reasonable distance is one way to take a photo. A telephoto lens from further away can achieve a similar outcome when shooting the same subject with the same camera.

Balancing all of these different factors gives you some sense of control over the scale of the portrait that you're able to take, no matter what you happen to be working with. The numbers don't have to be neat and tidy; in fact, you really don't need to worry about them at all in many cases. Instead, you should focus more on what you want to accomplish, and how the tools at hand can be used to meet this goal.

How Does Magnification Work in Photography?

The difference between each combination of contributing factors has a lot to do with the relationship between the size of the photosensitive plane of photography and the scale at which the lens projects the incoming light against it.

Specialty lenses, like macro lenses and telephoto lenses, increase the size of the projected image that the incoming light culminates into, relative to the area of the camera sensor or slide of film. An expanded version of the image projection takes up more space on the camera sensor, the physical size of which never changes.

We end up seeing "more" of the subject, which means more detail at a larger scale, at the cost of the periphery of what would have been the original photo. The rest of the original image still exists. It's just spilling out over the perimeter of the photosensitive plane because it has been magnified beyond this limiting factor.

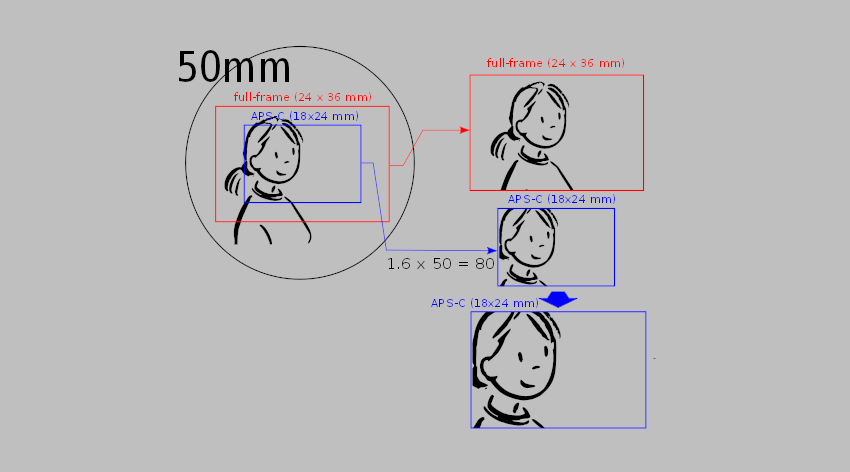

Two identical lenses will produce two different images when used alongside two camera sensors of different sizes. It's the reason why the cropped sensor of a Canon 7D produces a different image than the full, 35mm-equivalent sensor of a Canon 5D.

Your field of view is effectively reduced, but this is only because the projected image covers more of the sensor than the same image would if it were not being magnified. When both images are scaled to the same resolution, the difference in magnification becomes obvious.

Make Magnification Work for You

Is bigger always better? It depends on who you ask. Understanding your own needs well will lead you to the appropriate way to proceed.

The good news: no matter how big or small your subject of choice happens to be, there will always be a way to make the photo work out for you in the end. All that you have to do is give it a shot, no pun intended.