The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing governments to investigate citizens like never before. A confirmed COVID-19 case can transmit the coronavirus onto countless other people. Tracing any individual that encounters the deadly coronavirus could help stop further transmission, isolating the spread, and potentially assisting with the lifting of lockdown measures.

As you might expect, there is some opposition to an app that traces and matches your location. Even if it has a net positive effect, is tracing your location a breach of privacy?

So, how do COVID-19 contact tracing apps work? And can a contact tracing app protect your privacy?

What Is a COVID-19 Contact Tracing App?

A COVID-19 contact tracing app is a tool that governments and healthcare professionals can use to trace the movements of an individual who has coronavirus.

A contact tracing app will capture the locations a person has visited during the time they are suspected of having the coronavirus. After establishing a list of locations, the contact tracing app can trace any other smartphones that were in the vicinity of the individual during that period.

An app can send out messages to affected citizens automatically, inform those in high-risk groups to seek medical advice, and more. The sooner a person knows they were in contact with someone carrying COVID-19, the quicker they can begin to mediate their behavior, be that self-isolating or seeking treatment.

COVID-19 contact tracing app development is, understandably, in overdrive. There are various projects around the world attempting to create a contact tracing solution. The difficulty is balancing the need to locate, trace, and inform, versus the very real issue of protecting the privacy of the individual.

How Does a COVID-19 Contact Tracing App Work?

There are multiple coronavirus contact tracing apps in development. At the time of writing, at least 30 countries are developing or already implementing COVID-19 contact tracing apps. The apps use several different approaches and privacy frameworks.

There are two main approaches to coronavirus contact tracing.

- Centralized Contact Tracing: A centralized approach to COVID-19 contact tracing uses the network location of a smartphone, rather than an individual app. The centralized approach eliminates the need to download an app, decreasing the number of citizens that would avoid contact tracing apps. Centralizing contact tracing through network location creates a significant privacy issue, however.

- Decentralized/Privacy-Focused Contact Tracing: Privacy-focused contact tracing methods (also known as privacy-preserving contact tracing) do exist. These apps use a different range of smartphone technologies for monitoring and tracing. Several privacy-focused contact tracing frameworks use Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) connections to approximate a user's location and proximity to other smartphones. Furthermore, Apple and Google are working in partnership to develop a contact tracing project (more on this below).

It isn't just privacy advocates sounding their concerns regarding coronavirus contact tracing apps. The scale of contact tracing is forcing everyone to consider how such apps will protect user privacy.

Furthermore, the decentralized, privacy-focused options are not without fault. One idea mooted had support from hundreds of respected academics, privacy advocates, and security researchers. Yet, once the project published its project, many pulled their support, citing a lack of oversight and that the project would not protect privacy as first indicated.

How Can a Contact Tracing App Protect Privacy and Remain Effective?

That is the question each contact tracing protocol development team is attempting to solve. At the time of writing, five privacy-preserving contact tracing (PPCT) protocols are in development. Three PPCT protocols are garnering more interest than other options---though not all for the right reasons.

Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT)

PEPP-PT was one of the first privacy-preserving contact tracing apps to begin picking up development speed.

PEPP-PT uses BLE to track and log users in close proximity to a user. The protocol then sends the data to a centralized server for contact processing, where potentially infected users are contacted. If a user is a confirmed coronavirus case, they receive a request to upload their contact log for analysis.

Although PEPP-PT claims strong privacy credentials, the project received criticism regarding transparency on the functionality of the protocol, as well as why the PEPP-PT had released no open-source code for scrutiny.

When PEPP-PT did publish in-depth details of how the protocol works, including the use of centralized servers, researchers and academics associated with the project began switching support to the DP-3T project (see below). Over 300 academics and researchers removed their support from the project on April 20, 2020.

"Such apps can otherwise be repurposed to enable unwarranted discrimination and surveillance," said a joint letter signed by academics in over 26 countries. "It is crucial that citizens trust the applications in order to produce sufficient uptake to make a difference in tackling the crisis. It is vital that, in coming out of the current crisis, we do not create a tool that enables large-scale data collection on the population, either now or at a later time."

Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T)

Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing is an open-source contact tracing project that uses BLE to track and log users. Like PEPP-PT, the contact and location information uploads to a server.

However, DP-3T uses an "ephemeral, pseudo-random ID" to represent the user. It also uses the same pseudo-random ID to document any interaction with another user. The DP-3T app broadcasts the temporary random ID to other smartphones. Any smartphones in the same proximity also receive a temporary random ID.

If the user becomes a COVID-19 patient, they can upload their local app location data. The users remains anonymized through the pseudo-random ID. The app detects the potential for contact with other users and sends a message accordingly (also using the pseudo-random ID of the other users).

Although the DP-3T protocol still uses a central server, it has several integrated privacy protection features. For instance, the app shares no information with any healthcare service until the user uploads their location data. This prevents the abuse of personal data as no single entity receives a tranche of data, especially data not meant for a specific organization or otherwise.

The server itself cannot uncover an individual identity on the network, because each user keeps their data local until the point of upload.

Finally, the DP-3T project has confirmed that it will dismantle the app at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, any "data on the server is removed after 14 days."

Several countries are implementing DP-3T contact tracing apps to assist with stopping the spread of COVID-19.

Google/Apple PPCT Project

Google and Apple are working on a coronavirus contact tracing app that would utilize their smartphone operating systems (Android and iOS, respectively). As the two companies control the smartphone operating system market, the tech giants hold a unique place in the battle against COVID-19.

The "Gapple" PPCT project uses a similar system to DP-3T, using BLE interactions to trace users. The log uses randomized identifiers to protect the privacy of all parties. The identifiers change every 15 minutes to anonymize the data further.

Data is held locally for 14 days. If the user doesn't receive a contact tracing message during that time, the app deletes the data, including any identifiers.

Issues with Using Bluetooth Low Energy for COVID-19 Contact Tracing

As you have seen, each solution proposes using Bluetooth Low Energy for coronavirus contact tracing apps.

Bluetooth and its successor, Bluetooth Low Energy, are ubiquitous throughout most countries around the world. However, an estimated 2 billion mobile phones around the world do not use BLE. A further 1.5 billion use legacy phones that do not run a modern mobile operating system.

Exacerbating the issue is the fact that most of the people in that bracket are more vulnerable to COVID-19, be that due to age, location, or income demographic.

Another BLE issue is the technology itself. Bluetooth Low Energy can transmit over distances of 10 to 30 meters, depending on the device. The commonly accepted social distancing advice is to remain 2 meters apart from each other. But if your phone can ping someone up to 30 meters away, there will be false positives.

Due to the way the contact tracing apps work, a single false positive could cause a cascade of false-positive messages through the alleged connections of that user.

Furthermore, coverage is key to the efficacy of any privacy-preserving contact tracing app, BLE, or not.

In the UK, researchers from the University of Oxford estimate that at least 80 percent of the smartphone owning population must install the contact tracing app to reach a reasonable level of coverage. The figure equates to around 56 percent of the UK population.

Which leads to another issue. If someone doesn't want to use a COVID-19 contact tracing app, they just won't download it. A similar system developed in Singapore had an uptake of just 12 percent. That's not nearly enough to create an effective contact tracing system.

Will Contact Tracing Help Stop COVID-19?

There are issues regarding the implementation of coronavirus contact tracing apps. However, a slow consensus is building, recognizing that some form of social distancing management is going to have to be in place in order to return to "real life."

The onus is on building contact tracing apps that protect the privacy of the users. As you might expect, if there is a hiccup with a contact tracing app, it can expose private user data.

For example, an early iteration of a contact tracing app in South Korea broadcast the personal data of coronavirus cases while alerting those who may have come into contact. The developers quickly patched the flaw from the contact tracing app. Still, those fears surrounding privacy remain strong, especially in countries yet to begin widespread contact tracing testing.

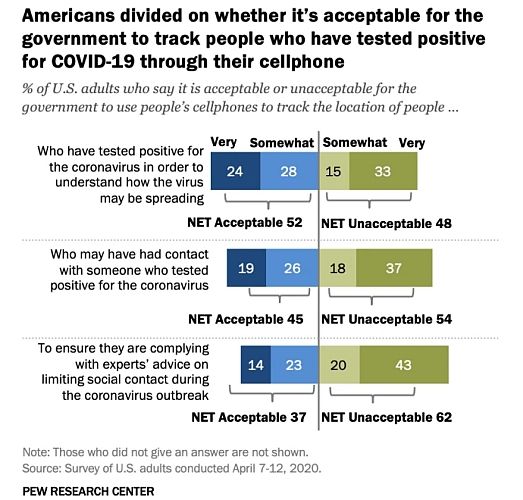

In the US, there is a strong indifference to COVID-19 contact tracing apps, with many respondents to a recent Pew Research study indicating little faith in the system.

The delicate balance between preserving privacy and working to protect public health is fraught with potential pitfalls. In Israel, the government proposes to use counterterrorism laws to instigate network-level tracking of all devices. That's beyond the pale and a level of intrusion that most citizens will never accept.

But if it means society and the economy can begin functioning as normal, some form of contact tracing is inevitable, at least in the short term.

Will Coronavirus Contact Tracing Destroy Privacy?

The idea of supporting another smartphone tracing method goes against our inbuilt desire for privacy. On the Joe Rogan Experience podcast, Edward Snowden explains in great detail how your smartphone is already the number one tracking tool in the world.

A series of protocols that extend tracking to every phone in your vicinity is another surveillance step.

On the other hand, COVID-19 is affecting millions of people around the world. The implementation of DP-3T stores data locally to stop any other party engaging with your location information until you catch the coronavirus.

If the government wanted to track you, they would already be doing it. An app that could save lives is a worthwhile endeavor in the short term, especially as many countries begin to relax lockdown regulations and begin to wonder what a 2nd COVID-19 peak might entail.

Part of the difficulty healthcare professionals face is misinformation regarding COVID-19. Check out these sites for trustworthy up to date coronavirus news. Another issue facing everyone is the surge in coronavirus-related phishing attacks. Here's how to spot a COVID-19 phishing attempt and how to stay safe.