It's 2015, and space is cool again.

SpaceX has rejuvenated public interest in space, and is already plotting a Mars mission. Forbes is doing profiles on asteroid mining startups. A coalition of private companies are building a spaceport in New Mexico. It's the most exciting period for space exploration since the last moon mission in 1972.

During that mission, astronaut Eugene Cernan ended humanity's last moonwalk with these words:

"As I take man's last steps from the surface [...] I'd like to just list what I believe history will record: that America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus Littrow, we leave as we come and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17."

In the 43 years since he spoke those words, a lot has happened. The Soviet Union fell. Computer technology exploded. The Concorde came and went. But, we never did go back to the moon. In fact, humans haven't been out of Low Earth Orbit since Apollo 17 returned.

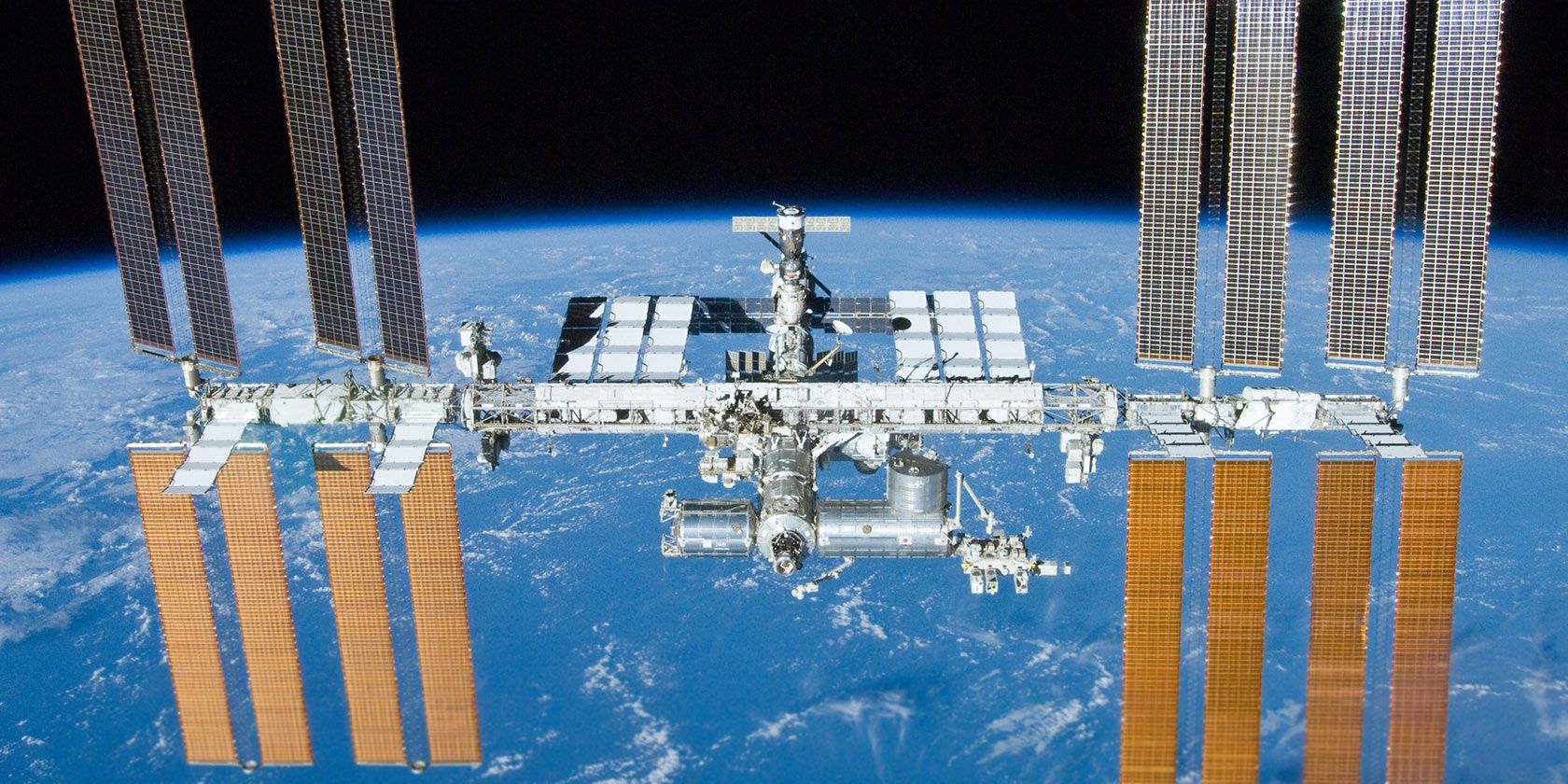

We've sent some probes, and landed robots on Mars. We built the shuttle and the ISS. None of that is ground-breaking. The first rocket to achieve Low Earth Orbit did so in 1961. The first "successful" Mars probe would touch down a decade later in 1971. The first space station went up in 1971. The lack of innovation smothered public interest in space, and killed the space opera as a genre.

What went wrong? What happened to NASA? And what's changing now? Let's wind the clock back.

Destination: Stagnation

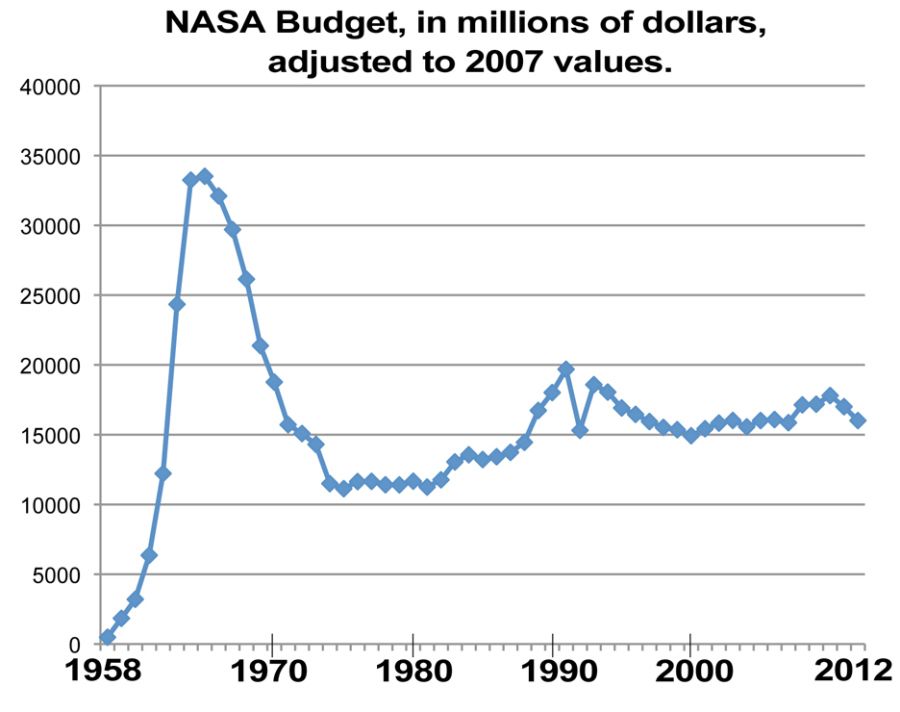

There's no way to tell this story without giving a starring role to NASA's budget (or, rather, lack thereof). Here's a graph of NASA's budget since the Apollo era.

Clearly, there have been some cutbacks. As the Cold War ebbed by the early 70's, it became clear that fears of Communist technological superiority had been overblown. The space race narrative fell apart, and so did public support for the expensive Apollo program. With the Vietnam war already going badly, Nixon chose to quietly cancel the last few missions and end Apollo. In some ways, this had been the plan from the beginning.

In 1968, George Trimble, Deputy Director of NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) sent a memo requesting that the Apollo program have a finite length, and a well-defined end-point.

"[...] that the accomplishment of the first lunar landing and safe return of the crew be defined as the end of the Apollo Program. This will give a crisp ending that everyone can understand and will be the minimum cost program. The Lunar Exploration Program, or whatever name is selected, will have a definable whole [sic] and can be planned and defended as a unit. This will avoid the Apollo Program dragging on to an ill-defined termination. . ."

It was assumed that the Apollo program would be followed up with a journey to Mars, or a long-term moon base. Instead, after the funding cuts, a decision was made to transition to orbital space exploration, including the construction of a large space station. Plenty of observers have laid the blame for the current space stagnation at the feet of short-sighted, penny-pinching regulators. This is a narrative I'd like to challenge.

While the NASA budget cutback was a factor in the decline of American space exploration, it's far from the whole story. Much of the blame lies with NASA itself. It lost focus and become embroiled in expensive technological dead-ends.

Consider this: Since the Apollo era, NASA's budget has fallen by about 50% -- but that's not shocking.

The basic R&D efforts on the rockets absorbed much of the extra money. After that R&D was done for the Saturn V, each moon launch cost a mere $375 million in 1970 (about $2.5 billion in 2015 dollars). NASA's modern budget of roughly $15 billion is plenty to sustain regular moon missions, if that were a priority.

Contrary to the popular belief -- the limiting factor is not financial.

If a moon mission doesn't excite you, what about Mars Direct? The meticulously budgeted bare-bones architecture for a manned mission to Mars and back would cost about $50 billion. If NASA devoted five years to the prospect, it's far from out of reach.

So, now that we see what we could have bought... what did we do with the money instead?

Stations and Shuttles

Let's talk about the ISS.

The ISS was subsidized by spreading it out among many countries, all of whom would benefit from the PR and research generated by it. The breakdown of costs are enlightening.

The USA spent $72.4 billion to construct its pieces of the station, and $50.4 billion more to lift it into orbit, for a grand total expense of $120.8 billion. The investments of Russia, Japan, the EU, and Canada add up to just $24 billion combined. So much for 'spreading the cost'

How efficient is the ISS compared to past space stations?

The ISS is a sharp departure from past space stations. It is built out of smaller modules in a more complex configuration than previous "single-room" stations. This is interesting technology, but expensive.

Launched immediately after the end of the Apollo program, our first station ("Skylab") cost $10 billion in modern dollars to build. It had an internal volume of about 360 meters cubed. The ISS cost about $150 billion with a volume of 907 cubic meters. The US could have spent $30 billion and launched three Sky-lab sized modules and built a station larger than the ISS for less than a fourth of the cost. The leftover $90 billion could have paid for a trip to Mars and twenty moon missions.

Consider the space shuttle itself -- the most visible form of space exploration since the Apollo program. NASA believed that by building a reusable space plane, it would be possible to reduce the cost of moving people and cargo to Low Earth Orbit.

Space planes have been a colossal failure in terms of reducing launch cost -- the added mass and complexity more than wipe out any benefits from reusability. Old-style disposable vehicles like the Russian Proton cost about $2300 per pound of cargo. The shuttle costs about $8000 per pound, more than triple the costs.

Worse, the complex heat shield and the need for secondary boosters made the shuttle dangerous as space vehicles. Of the five shuttles, two exploded, and 1.5% of missions ended in fatalities.

The failure of the Shuttle as a cost-saving measure must have been clear early in the design process, but NASA plowed on, running the shuttle program from 1981 to 2011. That's three decades of horrific waste. The shuttle program cost $209 billion. The money saved just by using vehicles we already had would be more than $100 billion by now. That's enough to go to Mars and back twice, putting boots on the ground on the red planet to answer fundamental questions about the origins of life.

NASA has come around to the notion that the shuttle program was a mistake. In 2005, NASA-chief Michael Griffin told USA Today

"It is now commonly accepted that was not the right path [...] We are now trying to change the path while doing as little damage as we can."

What would have been possible without the shuttle program?

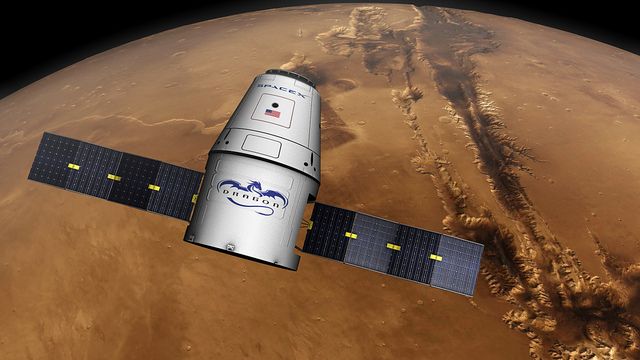

Consider SpaceX's Dragon vehicle, a modernization of the more traditional rocket designs. The Dragon V1 can carry 13,228 pounds of cargo, at a net cost about $13 million, or a little under $1000 per pound -- eight times less than the shuttle, and less than half the cost of the old Proton. This is a vehicle that's only been in development for a few years, and was created on a tiny fraction of NASA's budget. The next iteration, the Dragon V2, which will be reusable, is expected to drop the price much further (perhaps down to under $500 per pound).

The Dragon V2 will use a simple and robust gum-drop shaped re-entry capsule of the kind used by everything from the Gemini program to the Soyuz. The innovation is the use of small rockets to allow the capsule to make a controlled landing instead of a splashdown, a feature they pioneered with the "grasshopper" prototype. This is much simpler than attempting to build a space plane, and likely far cheaper.

The common theme here might be called "false progress". NASA has wasted an astonishing amount of money pursuing technical "advancements" that were not improvements. Space planes and modular space habitats are not good ideas in the real world.

Perhaps one problem is that NASA doesn't have the correcting influence of market pressures. Market forces tend to eliminate this kind of waste, as competitors with better, cheaper technology win out. In a thriving space exploration market, space planes would remain a forgotten footnote, the Nintendo Virtual Boy of launch vehicles.

NASA is also vulnerable to political pressures of the shortsighted kind. Space planes look like the future if you're a politician who's never taken an engineering class. Maybe they can imagine their grandkids climbing aboard one at an airport one day, so they push the program over the complaints of engineers. Building a space station in cooperation with four other nations sounds like a great idea, provided you're a politician who's more interested in headlines than science. The NASA of the last forty years is a vivid example of what happens when you let politics take the place of scientific prudence.

Who Killed the Space Opera?

People react emotionally to criticism of NASA. Let me clarify that this critique isn't coming from a hatred of space exploration. I'm not upset about the tax burden imposed by NASA, which is minimal. I'm upset that we aren't getting nearly as much space exploration as we could be for the money we're spending. Some beautiful and fascinating stuff has come out of the ISS and shuttle programs. It's just sad to think of what might have been.

The recent explosion of space progress is coming, not from NASA, but from a handful of small, private companies with a strong profit motive to reduce costs, and an ideological devotion to the cause of affordable space exploration.

SpaceX stripped of all the PR glitz is exciting. Its founder and owner, Elon Musk, views it as a heroic effort to safeguard humanity against extinction.

"It's funny, not everyone loves humanity. Either explicitly or implicitly, some people seem to think that humans are a blight on the Earth's surface. They say things like, "Nature is so wonderful; things are always better in the countryside where there are no people around." They imply that humanity and civilisation are less good than their absence. But I'm not in that school. I think we have a duty to maintain the light of consciousness, to make sure it continues into the future."

Musk is only the most recent bearer of this philosophy of space exploration. Scientists have seen space exploration as a moral imperative for hundreds of years. In 1610, Kepler wrote to Galileo about the possibility of human travel to the recently discovered other planets of the solar system.

"Let us create vessels and sails adjusted to the heavenly ether, and there will be plenty of people unafraid of the empty wastes. In the meantime, we shall prepare, for the brave sky-travellers, maps of the celestial bodies."

That's the dream that drove Galileo, Werner Von Braun, and Elon Musk -- and it's a dream that is, finally, starting to come true. Today, private space companies are stretching the limits of what is possible. Public interest in space clearly exists, and as the boom proves -- so does the money. What's necessary is the political and institutional will to take big risks without losing sight of practicality. This will involve abandoning some less ambitious projects already in motion, which will be controversial.

It will also be worthwhile. There's a lot at stake here: if we allow the new space boom to fizzle out, we're in for more decades of retarded science, vanity projects, wasted money, and squandered ambitions.

I can't imagine anything more depressing.

Image Credits: NASA Space Shuttle Endeavor, by Andrew Adams, Soviet Space Shuttle Diagram, Steve Jurvetson, CATS Installed on ISS, by GSFC, US Eastern Seaboard At Night From ISS, NASA's Earth Observatory, Moon Shadow by James Jordan, Apollo 11 East Crater Panorama by GSFC, Red Dragon by SpaceX, SpaceX Dragon by Kevin Gill