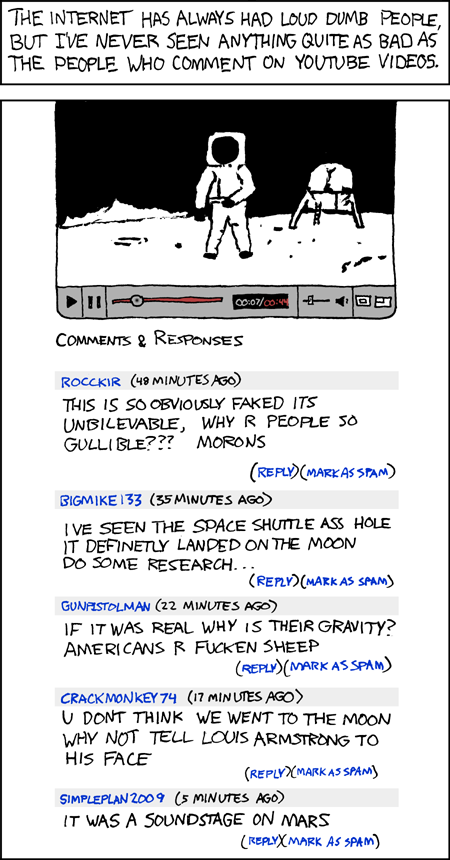

Comments can be bad for science. That's what Popular Science argued when it announced it was shutting down its comment section back in September.

"A politically motivated, decades-long war on expertise has eroded the popular consensus on a wide variety of scientifically validated topics," wrote online editor Suzanne LaBarre. "Everything, from evolution to the origins of climate change, is mistakenly up for grabs again."

This is undemocratic. It reduces the power of the reader. It's contrary to everything the Internet believes to be sacred.

And it just might be exactly the right thing for Popular Science to do.

Medium Matters

It's a phrase every intro-level media class teaches students: "The medium is the message". First uttered by Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, it points to how the way you experience information is part of the message you get from it.

On a really basic level this isn't so hard to understand. To binge on Breaking Bad using Netflix is a completely different experience than watching it week-to-week on TV. The former medium allows you to watch episodes closely together, meaning you'll notice a lot about the ongoing story arch – experiencing the show as a really, really long movie. Watch week to week, however, and you'll have more time to reflect on individual episodes as self-contained units – possibly noticing things you wouldn't while binging. Neither approach is right or wrong, but the way you experience Breaking Bad will change how you think of it.

In Frozen Music, a particularly brilliant episode of the always-awesome 99% Invisible podcast, host Roman Mars makes a similar point about music recordings:

I once bought vinyl albums and cassette tapes, where there were two first songs per album, Side A and Side B. The energy of a first song makes it stand apart, at least in my head it does. Then the CD came along and eliminated Side B and there was only first song, and the actual number of a track (that you see prominently on the UI) became my index for sorting songs. Then MP3s jumbled my sense of track order, and albums began to feel more like a loose grouping of individual pieces rather than a conceptual whole.

Mars is pointing out how the tools used to listen to music alters the way he experiences it. You can probably think of other examples, such as how conversation over SMS is different than over phone, or how reading an ebook on a tablet is different than reading a paper book. It's the different experiences that changes how you perceive information in subtle ways.

This is all my extremely simplified version of McLuhan's idea, but it's sufficient for what I'm trying to get across here: that the medium you use to consume information affects the way you perceive it. The Internet is the defining medium of our age, and we're still working out its message.

Comments as a Medium

"But what does this have to do with comments?" you're asking. Well, almost as long as newspapers and magazines have been on the web they've allowed comments. These almost always show up at the end of articles, and it's not hard to understand why: they give readers a reason to stay on a page longer without a lot of extra work on the part of site owners.

But what's the message of Internet comments, as a medium? You could say it's that all ideas are equally valid. The author states her view, sure, but then readers can state theirs. Everyone decides what's true based on what they find convincing.

Think about it: comments are staggeringly democratic. You, after reading (or not reading) an article have the ability to supplement it with your own views. This could be a thank you to the writer, or it could be an attempt to undermine the writer's credibility. It could be a supplemental point, or it could also be a completely unprompted appeal to support Ron Paul's 2016 bid for the presidency.

To put the unfiltered thoughts of anyone with the inclination to do so below articles is to give these thoughts value. And for a site like ours, which acts as a collaborative way for people to find cool web sites and apps, that can be awesome. Readers frequently point out amazing alternatives to the tools we profile, helping readers find more cool stuff and us to find the next tools we're going to profile.

So a potential message of comments may be that your view is just as valid as that of the authors. And again, I would argue that message makes sense on a site like ours – we see ourselves simply as regular people who love technology enough to write about it. But does that message have a place below articles outlining the latest scientific news?

Maybe. Maybe not.

Science Doesn't Care What You Believe

"Even a fractious minority wields enough power to skew a reader's perception of a story, recent research suggests," said Popular Science's article about their decision to stop allowing comments. They're pointing to research done where the presence of online comments criticizing a study's conclusion skews people's perception of that study.

To Popular Science, giving comments so prominent a placement as directly below an article helps perpetuate fundamentally unscientific ways of thinking.

"But isn't this undemocratic?", you might be asking. "Shouldn't we allow everyone to state their viewpoint and arrive at their own conclusion?"

Well, science isn't democracy: it's a process. And science, as a process, does not care what the majority of people believe. It's about proposing a theory, then using observation and data to try to prove that theory wrong.

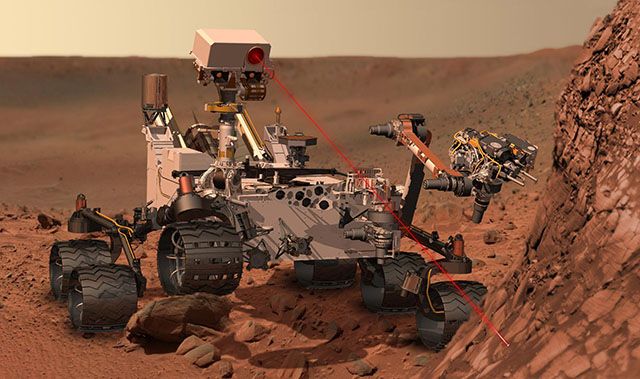

You might not like some of the conclusions that process leads to, but you have it to thank for everything from modern health care to robots on Mars to the device you're reading this article on right now. It's important people understand this, and Popular Science believes comments composed in mere seconds could undermine research in the public mind.

So science, as a method, is arguably incompatible with comments, as a medium.

Questioning Comments

Two more ideas. First: it's worth noting that the vast majority of web users don't leave comments. For example: the typical MakeUseOf article is seen by thousands of people the day it's posted, but it's extremely rare for an article to get more than 100 comments. You could argue, then, that comments represent not popular opinion but that of a small minority of readers. Should that minority be given so much power to influence the way people process scientific information?

Second: comments below an article are far from the only tool Internet users have for communicating with writers. Social networks offer a direct line of contact, not to mention a powerful platform for discussion. Disabling comments doesn't shut down conversation: it moves it elsewhere. So why should Popular Science allow potentially inaccurate statements on their own site to skew the public perception of scientific research?

Should You Turn Comments Off?

Wondering what the web would be like without comments? Shut up for Chrome allows you to turn off comments for most popular sites. You'll be amazed how much less time you waste on the Web, and how little actual information you miss out in the process (MakeUseOf aside: our commentors are awesome).

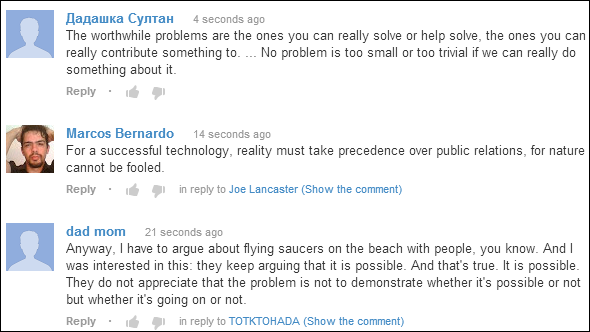

Oh, and there are also ways to improve comments on YouTube, most of which replace the text with quotes people like Feynman and Nietzsche.

Are you wondering whether you should allow comments on your own blog? Nancy outlined the pros and cons of comments, so check that out if you're on the fence.

Of course, there's nothing vaguely scientific about this article: it's opinion through and through. As such, I'm thrilled to hear your thoughts. Do comments undermine science? You already know my viewpoint, so let's talk below.

Image Credit: YouTube Comment comic courtesy XKCD; Mars Rover (NASA)