Ransomware is a type of malware that prevents the normal access to a system or files, unless the victim pays a ransom. Most people are familiar with the crypto-ransomware variants, where files are encased in uncrackable encryption, but the paradigm is actually much older than that.

In fact, ransomware dates back almost ten years. Like many computer security threats, it originated from Russia and bordering countries. Since its first discovery, Ransomware has evolved to become an increasingly potent threat, capable of extracting ever larger ransoms.

Early Ransomware: From Russia with Hate

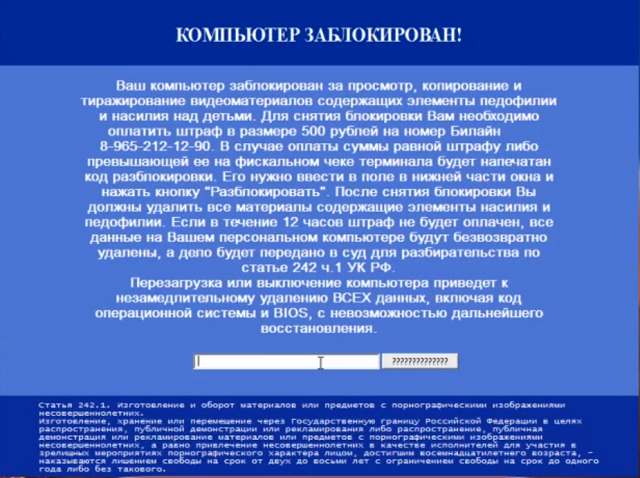

The first ransomware specimens were discovered in Russia between 2005 and 2006. These were created by Russian organized criminals, and aimed largely at Russian victims, as well as those living in the nominally-Russophone neighboring countries like Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan.

One of these ransomware variants was called TROJ_CRYZIP.A. This was discovered in 2006, long before the term was coined. It largely affected machines running Windows 98, ME, NT, 2000, XP, and Server 2003. Once downloaded and executed, it would identify files with a certain file-type, and move them to a password-protected ZIP folder, having deleted the originals. For the victim to recover their files, they would have to transfer $300 to an E-Gold account.

E-Gold can be described as a spiritual predecessor to BitCoin. An anonymous, gold-based digital currency that was managed by a company based in Florida, but registered in Saint Kitts and Nevis, it offered relative anonymity, but quickly became favored by organized criminals as a method to launder dirty money. This lead the US government to suspend it in 2009, and the company folded not long after.

Later ransomware variants would use anonymous crypto-currencies like Bitcoin, prepaid debit cards, and even premium-rate phone numbers as a payment method.

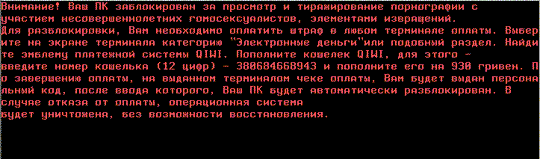

TROJ_RANSOM.AQB is another ransomware variant identified by Trend Micro in 2012. Its method of infection was to replace the Master Boot Record (MBR) of Windows with its own malicious code. When the computer booted up, the user would see a ransom message written in Russian, which demanded that the victim pay 920 Ukrainian Hryvnia via QIWI -- a Cyprus-based, Russian-owned payments system. When paid, the victim would get a code, which would allow them to restore their computer to normal.

With many of the identified ransomware operators being identified as from Russia, it could be argued that the experience gained in targeting the domestic market has made them better able to target international users.

Stop, Police!

Towards the end of the 2000s and the start of the 2010s, ransomware was increasingly being recognized as a threat to international users. But there was still a long way to go before it homogenized into the potent, crypto-ransomware variant we see today.

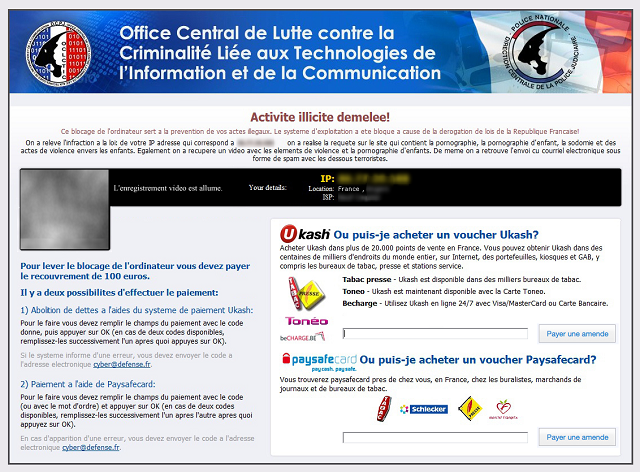

Around this time, it became common for ransomware to impersonate law enforcement in order to extract ransoms. They would accuse the victim of being involved with a crime -- ranging from mere copyright infringement, to illicit pornography -- and say that their computer is under investigation, and has been locked.

Then, they would give the victim a choice. The victim could choose to pay a "fine". This would drop the (non-existent) charges, and return access to the computer. If the victim delayed, the fine would double. If the victim refused to pay entirely, the ransomware would threaten them with arrest, trial, and potential imprisonment.

The most widely recognized variant of police ransomware was Reveton. What made Reveton so effective was that it used localization to appear more legitimate. It would work out where the user was based, and then impersonate the relevant local law enforcement.

So, if the victim was based in the United States, the ransom note would appear to be from the Department of Justice. If the user was Italian, it would adopt the styling of the Guardia di Finanza. British users would see a message from the London Metropolitan Police or Strathclyde Police.

The makers of Reveton covered all their bases. It was localized for virtually every European country, as well as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. But it had a flaw. Since it did not encrypt the user's files, it could be removed without any adverse effects. This could be accomplished with an antivirus live-CD, or by booting into safe mode.

CryptoLocker: The First Big Crypto-Ransomware

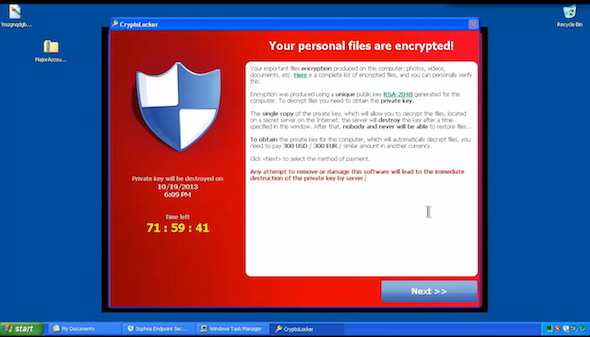

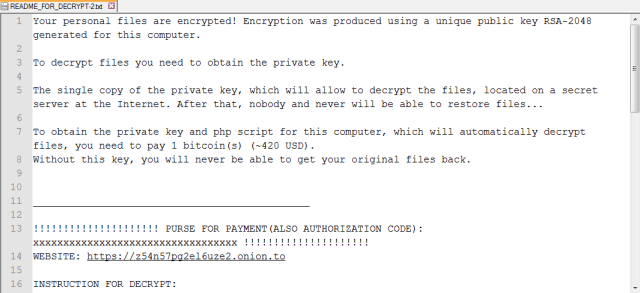

Crypto-ransomware has no such flaw. It uses near-unbreakable encryption to entomb the user's files. Even if the malware was removed, the files remain locked. This puts an immense pressure on the victim to pay up.

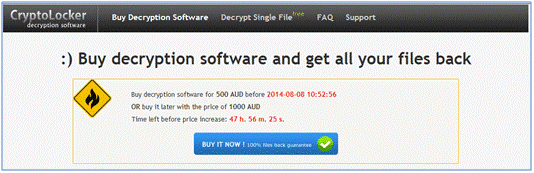

CryptoLocker was the first widely-recognizable crypto-ransomware, and appeared towards the end of 2013. It's hard to estimate the scale of infected users with any degree of accuracy. ZDNet, a highly-respected technology journal, traced four bitcoin addresses used by the malware, and discovered that they received about $27 million in payments.

It was distributed through infected email attachments, which were propagated via vast spam networks, as well as through the Gameover ZeuS botnet. Once it had compromised a system, it would then systematically encrypt document and media files with strong RSA public-key cryptography.

The victim would then have a short amount of time to pay a ransom of $400 USD or €400 EUR, either through Bitcoin, or through GreenDot MoneyPak -- a pre-paid voucher system favored by cyber criminals. If the victim failed to pay within 72 hours, the operators threatened that they would delete the private key, rendering decryption impossible.

In June 2014, the CryptoLocker distribution servers were taken down a coalition of academics, security vendors, and law enforcement agencies in Operation Tovar. Two vendors -- FireEye and Fox-IT -- were able to access a database of private keys used by CryptoLocker. They then released a service which allowed victims to decrypt their files for free.

Although CryptoLocker was short-lived, it definitively proved that the crypto-ransomware model could be a lucrative one, and resulted in a quasi digital arms race. While security vendors prepared mitigation, criminals released ever-sophisticated ransomware variants.

TorrentLocker and CryptoWall: Ransomware Gets Smarter

One of these enhanced ransomware variants was TorrentLocker, which emerged shortly after the fall of CryptoLocker.

This is a rather pedestrian form of crypto-ransomware. Like most forms of crypto-ransomware, its attack vector is malicious email attachments, especially Word documents with malicious macros. Once a machine is infected, it will encrypt the usual assortment of media and office files using AES encryption.

The biggest difference was in the ransom notes displayed. TorrentLocker would display the ransom required in the victim's local currency. So, if the machine infected was based in Australia, TorrentLocker would display the price in Australian dollars, payable in BitCoin. It would even list local BitCoin exchanges.

There have even been innovations in the infection and obfuscation process. Take CryptoWall 4.0, for example, the latest strain in the feared family of crypto-ransomware.

This has changed the way it infects systems, and now renames all infected files, thus preventing the user from determining what has been encrypted, and making it harder to restore from a backup.

Ransomware Now Targets Niche Platforms

Overwhelmingly, ransomware targets computers running Windows, and to a lesser extent smartphones running Android. The reason why can mostly be attributed to market share. Far more people use Windows than Linux. This makes Windows a more attractive target for malware developers.

But over the past year, this trend has started to reverse -- albeit slowly -- and we are starting to see crypto-ransomware being targeted towards Mac and Linux users.

Linux.Encoder.1 was discovered in November, 2015 by Dr.Web -- a major Russian cyber-security firm. It is remotely executed by a flaw in the Magento CMS, and will encrypt a number of file-types (office and media files, as well as file-types associated with web applications) using AES and RSA public key cryptography. In order to decrypt the files, the victim will have to pay a ransom of one bitcoin.

Earlier this year, we saw the arrival of the KeRanger ransomware, which targeted Mac users. This had an unusual attack vector, as it entered systems by infiltrating the software updates of Transmission - a popular and legitimate BitTorrent client.

While the threat of ransomware to these platforms is small, it is undeniably growing and cannot be ignored.

The Future of Ransomware: Destruction as a Service

So, what does the future of ransomware look like? If I had to put it into words: brands, and franchises.

First, let's talk about franchises. An interesting trend has emerged in the past few years, in the respect that the development of ransomware has become incredibly commoditized. Today, if you get infected with ransomware, it's entirely plausible that the person who distributed it, is not the person who created it.

Then there's branding. While many ransomware strains have earned name-recognition for the destructive power they possess, some manufacturers are aiming to make their products as anonymous and generic as possible.

The value of a white-label ransomware is that it can be rebranded. From one main ransomware strain, hundreds more can emerge. It's perhaps this reason why in the first quarter of 2015, over 725,000 ransomware samples were collected by McAfee Labs. This represents a quarterly increase of almost 165%.

It seems extremely unlikely that law enforcement and the security industry will be able to hold back this surging tide.

Have you been hit by ransomware? Did you pay up, lose your data, or manage to overcome the problem some other way (perhaps a backup)? Tell us about it in the comments!

Image Credits:privacy and security by Nicescene via Shutterstock