When upgrading a camera, one of the biggest choices you have to make is whether to invest in prime or zoom lenses. Primes are sometimes thought of as being more appealing to enthusiasts, but zoom lenses have their place too. You just need to know what you're getting, and where their strengths and weaknesses lie.

Here's everything you need to know about DSLR zoom lenses.

What Is a DSLR Zoom Lens?

A zoom lens is a camera lens with a variable focal length. You can zoom smoothly from the widest angle to the longest angle, stopping at any point in between. In short, it lets you zoom in and out (though not all zoom lenses let you zoom way in -- it just means that they can change focal lengths). You get the focal lengths of several prime lenses without ever having to switch.

Anatomy of a Zoom Lens

Zoom lenses may differ in small ways, but they all share a similar design and layout.

The biggest difference across models is the aperture ring. Most cameras adjust the aperture through an on-body dial rather than a ring on the lens. Fuji is the main exception to this.

For manual focus, most consumer zooms use a focus-by-wire system. When you move the focus ring the lens sends a message to the camera body telling it to adjust focus. Turning the ring doesn't move the lens elements directly.

How to Read the Specs of a DSLR Zoom Lens

Lenses don't have friendly brand names. They're known by the specs alone. Most often you'll see them referred to in a simplified form, like an 18–55mm f3.5-5.6, but the actual name can be as unwieldy as Fujifilm 55-200mm f/3.5–4.8 R LM OIS XF Fujinon Lens.

This tells you almost everything you need to know about the lens, as long as you understand what all the terms indicate.

The typical things you'll see in a lens name are:

- manufacturer (e.g. Nikon) -- Showing whether it is a first- or third-party lens.

- focal length (e.g. 18–55mm) -- The maximum and minimum focal length, measured in mm.

- aperture (e.g. f/2.8–4) -- The maximum aperture at the ends of the zoom range.

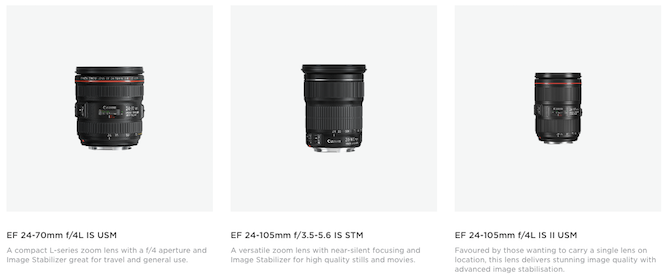

- series (e.g. L, XF) -- Often used to separate a manufacturer's entry-level and premium ranges.

- features (e.g. OIS, WR) -- Other features of the lens, from image stabilization and weather sealing to lens coating and glass design.

- compatibility (e.g. Canon fit, DX) -- The camera and mount the lens is designed for.

Extra Features

The various extra features you'll get vary from one zoom lens and manufacturer to another.

Weather sealing is a welcome addition if you shoot outdoors, and you tend to pay a small premium for it. Weather sealing is best interpreted as "rainproof" -- definitely not the same thing as "waterproof" -- but it only works if your camera body is also weather sealed.

Optical image stabilization is also worth having, especially on long lenses. Some cameras have it integrated into the body, so it's not needed in the lens. Confusingly, stabilization is given a different name by different manufacturers:

- IS (Canon)

- VR (Nikon)

- OIS (Fuji, Panasonic)

- OSS (Sony)

The other features vary between manufacturers, and are often technical details that you won't need to consider when shopping for a lens. For example, you might see "USM" listed on Canon lenses. This stands for Ultrasonic Motor, and is a type of autofocus motor.

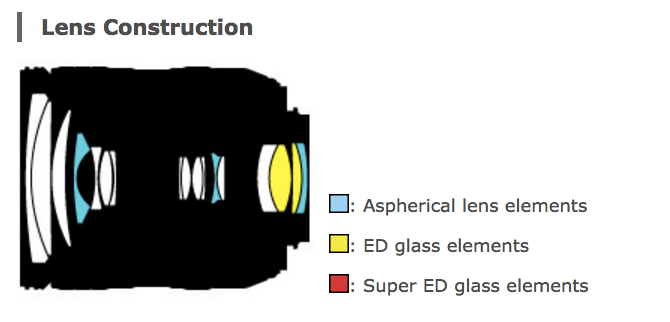

One other thing you'll often see listed on a specs sheet is the number of elements and groups in the lens. Elements refers to the number of individual pieces of glass inside the lens, and groups is how many groups they are split into (some of the elements may be fixed together). It's all very complex -- more often means better, but this is not a fixed rule.

Range and Focal Length

The range of a zoom lens is indicated by two numbers measured in millimeters, such as "18–55mm." The first number shows the focal length with the lens zoomed out, and the second number with the lens zoomed in.

Compact and bridge cameras refer to their zoom range as a multiplier, like "3x zoom" or "10x zoom." DSLR and mirrorless zooms don't. If you want to work it out in this way, just divide the two focal lengths together to get the answer. For example: 55/18=3.05, therefore a kit lens has a 3x zoom.

Types of Zoom

Zoom lens can be grouped into four main types, from general purpose to specific. These focal lengths are given for a crop sensor.

- Standard zoom (18–55mm) -- Most commonly seen on kit lenses, it goes from medium-wide to medium telephoto, and is a solid all-rounder.

- Super zoom (18–200mm) -- From medium-wide to telephoto, a super zoom replaces the need for multiple lenses and is good for travel.

- Wide zoom (10–20mm) -- A wide-angle zoom goes from ultra-wide to medium-wide, and is good for architecture and landscapes.

- Telephoto zoom (100–400mm) -- A long lens can be good for portraits as well as wildlife and sports photography.

Field of View and Crop Factor

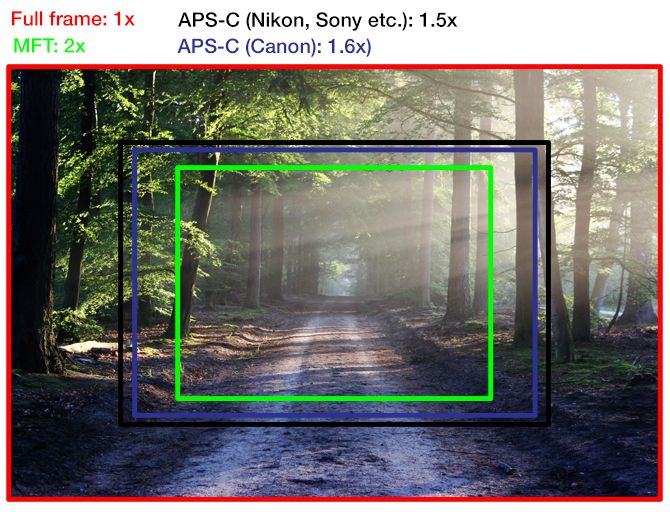

The focal length of a lens is relative to the lens itself, so 18mm is always 18mm no matter what body you mount your lens on.

However, a lens's field of view is not fixed. It depends on the size of the camera's sensor, and this is referred to as the crop factor.

A full-frame digital sensor is the same size as the old 35mm film. Crop sensors, like APS-C or micro four-thirds, are cropped to a smaller size. The more the sensor is cropped (the smaller it is), the narrower the field of view.

The result is that a lens will appear more zoomed in when used with a crop sensor, and you need a wider lens to achieve an equivalent wide angle.

The crop factor for APS-C is 1.5x, or 1.6x for Canon. For micro four-thirds (MFT) it's 2x. Therefore, an 18–55mm kit zoom on APS-C has the same field of view as a 14–42mm on MFT.

Perspective

Using a DSLR zoom lens enables you to experiment with the perspective changes that come with different focal lengths. These are effects you don't get by "zooming with your feet" with a prime lens or by simply cropping an image to zoom in.

Keep the foreground object in roughly the same part of the frame and you'll see that using a wider angle pushes the background further back, while zooming in compresses the image and pulls the foreground forward.

Aperture

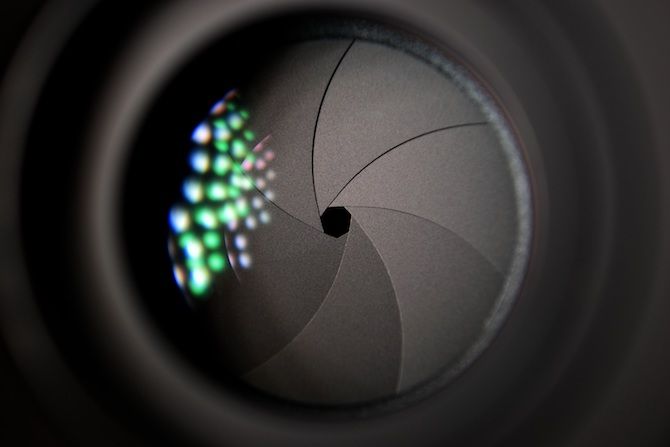

Aperture refers to the opening at the back of the lens that controls how much light is let in. It's measured in f-stops, and is displayed as, say, "f/2.8" on the spec sheet. F-numbers are somewhat counter-intuitive, insofar as a smaller f-number indicates a wider aperture and that the lens lets in more light. You can read more on it here.

Most zoom lenses in the consumer and enthusiast brackets have a variable maximum aperture. This is shown as an aperture range: the first f-number represents the maximum aperture when the lens is zoomed out, and the second number the maximum when it is fully extended.

Take for example a typical consumer DSLR kit lens, an 18–55mm, f/3.5–5.6. The maximum aperture is f/3.5 at 18mm and f/5.6 at 55mm. At the various focal lengths in between, the aperture is also somewhere in between.

However, these in-between stages don't progress linearly. The only way to find the maximum aperture of this lens at, say, 35mm would be to check reviews or get feedback from existing users.

Zooms can also have a constant maximum aperture throughout the zoom range. These lenses are almost always larger and more expensive, and tend to be aimed at pros.

Minimum aperture is less important, as you'll rarely use it. But it is constant on all zooms, and usually somewhere between f/16 and f/22.

Bokeh With a Zoom Lens

Because of the physical and technical difficulties in building zoom lenses with large apertures, most consumer zooms can be fairly described as slow, and they get slower the further you zoom in.

This means that you need to use a slower shutter speed than you would with a wider aperture lens, and that you'll get a bokeh effect: the background of the image will be out of focus. For shooting portraits, or for shooting in low light conditions, you may be better off with a fast (wide aperture) prime lens.

You can use a DOF simulator to see the effect of different apertures on depth of field and bokeh at various focal lengths.

Quality and Distortion

Zoom lenses are remarkably complex pieces of engineering. Each one contains multiple pieces of glass, or lens elements, that move closer together or further apart in order to change the magnification and maintain focus.

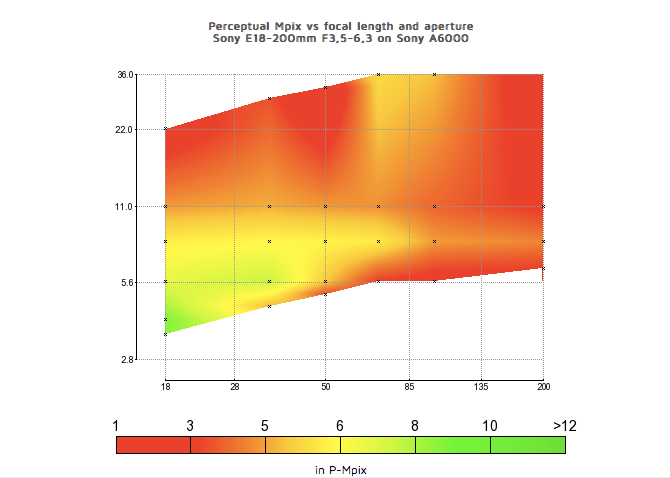

A basic compact kit lens might have eight or nine elements, while a bigger, more advanced lens could have 20 or 30. Getting a lens to remain sharp and distortion-free across the entire frame at every focal length and every aperture is a massive challenge, and most lenses have weaknesses.

The Sweet Spot

Every lens has a sweet spot where it is at its sharpest at either a specific focal length or aperture. For aperture, it's often 2–3 stops down from the maximum, so an f/2.8 lens would be sharpest at f/5.6–f/8. For focal length, the rule of thumb is that a lens is most likely to be softest at the extreme ends of the zoom range.

Zooms can also be prone to other issues. Barrel distortion can be apparent at the wide end, and pincushion distortion at the long end. The effect of both is that straight lines appear slightly curved. However, they will normally be fixed in camera if you shoot in JPEG format, and you can fix distortion in Lightroom if you're shooting RAW.

Distortion and quality issues are often related to the price and complexity of a lens. A cheap kit lens will be lower quality than something much more expensive. Zooms covering a very long range might also suffer due to the complexity of their design. The reviews at DxOMark tests all lenses for sharpness and distortion at all apertures and focal lengths so you check can how yours performs.

When Should You Use a Zoom?

The biggest arguments in favor of using DSLR zoom lenses are convenience and price. They allow you to shoot at several focal lengths without having to carry extra lenses, or constantly swap them. Buying one lens is also much cheaper than buying lots of separate ones (although a single prime will be cheaper than a zoom of the same quality).

Take a classic three-prime-lens setup, for example. In 35mm equivalent terms, you might have a 28mm, 50mm, and 85mm lens. A single kit lens covers all three of these focal lengths. Switch to a superzoom lens and you might be replacing five primes.

The convenience and price factors can also be important if you shoot a lot of video, as you're likely to want to switch focal lengths more often.

Zoom lenses are less suitable if you want to maximize your creative options. Even a budget prime lens will be two or three stops faster than most zooms at the equivalent focal length. They'd be a better choice if you want to shoot in low light or to soften the background of your images. Similarly, macro photography is better served by a prime lens.

You Need a Zoom Lens

Zoom lenses offer a level of flexibility that you cannot get with anything else. It reduces the chance that you'll ever miss a shot because you've got the wrong lens mounted at the wrong time. Or -- worse -- because you left your telephoto lens at home, thinking you wouldn't need it.

There may be compromises along the way. But so long as you understand their limitations, it's essential for every photographer to have at least one zoom in their bag.

Do you shoot with zoom lenses? Which ones do you recommend? Or are you primes all the way? Join the discussion in the comments below.

Image Credit: pisaphotography via Shutterstock.com