The hideous thing lurches at you from the crypt, slicing frantically at your stomach. You can almost feel the sword go through you. You scream girlishly, spraying fire from your fingertips as the lich crumples like a dying moth. You let yourself relax for a moment before noticing that the monster's sword is still stuck in your groin. You turn around. The knight is laughing at you. Even your girlfriend, the druid, is hiding a smile. You pull it out with as much dignity as possible. They aren't really here, you remind yourself, and none of this is really happening.

This isn't real life: this is the Metaverse.

People have been talking about Virtual Reality for a long time. Snow Crash came out in 1992, twenty-two years ago, and introduced the now-popular idea of the Metaverse - a persistent, globe-spanning virtual world in which billions of people shop, socialize, and relax.

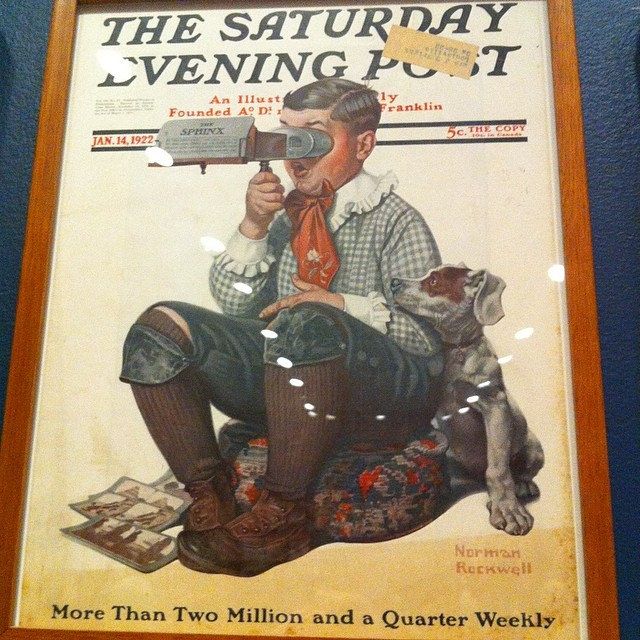

The book was profoundly forward-looking, but the idea of the Metaverse is showing its age, and it's not hard to see why. This is what the state of the art in computer graphics looked like in 1992, running on the best PC hardware available at the time.

When John Carmack and Michael Abrash made the world's first online multiplayer shooter Quake, they were trying, in a small way, to fulfill the vision of the Metaverse they'd read about in Snow Crash. The point here is that 1992 was a long, long time ago. There are kids born that year who graduated from college a few months ago.

At the time, dreamers like Jaron Lanier talked up this vision of the Metaverse, using it to sell the hopelessly primitive VR technology of the time. This led to the spectacular flop that poisoned public goodwill against the technology for years.

Now, more than two decades later, the technology is finally starting to arrive to fulfill some of those virtual reality promises. The Oculus Rift is on track to bring VR to the masses before the end of next year, and the technology is showing every sign of being a growth area as big as smartphones were in 2007. A lot of people are looking forward to their dreams of the Metaverse finally coming true. It's a very exciting time to be alive.

However, I would like to take a step back from the dream of the Metaverse, and take a critical look at it. It's not 1992 anymore, and we have the benefit of experience that was not available when people first began talking about these issues.

The first graphical MMO, Neverwinter Nights, went online in 1991, and may have contributed to the inspiration for Snow Crash. The first 3D MMO, Meridian 59, didn't launch until 1995. If we re-evaluate these ideas with the benefit of hindsight and a greater understanding of what virtual reality technology is actually going to look like, we may find that what everyone really wants is not the same as what we all thought we wanted in 1992.

So what's wrong with the good-old-fashioned Metaverse?

5. You Don't Actually Want Everyone Sharing One World

MMOs, in all their success, have run into their share of surprises. Way back in the day, when the sizes of worlds we could sustain were growing exponentially, it seemed obvious that the long-term goal was to have everyone present together in one world at the same time, just like the real world. However, developers quickly discovered that this was undesirable.

Very few games (with the notable exception of EVE Online) have combat mechanics that even make sense when you're talking about interacting with hundreds of other players, much less the tens of thousands you sometimes get in one place if you put all the players in the same instance of the virtual world.

As far as social interactions go, anyone who's ever gone to a rowdy party knows that it really isn't practical to interact with more than about thirty people at the same time. Having a whole bunch of people in one place rapidly devolves into a mess of bodies and speech that you don't get much value from. We don't even like crowds in real life!

The solution, in the case of almost every MMO, is server instancing: you split the crowd into manageable numbers, and give them each a separate copy of the part of the area they're in. The Metaverse, as traditionally imagined, would be the ultimate default subreddit: an unfiltered firehose of humanity, full of sound and fury but not much of any actual significance.

The Metaverse that people are actually trying to build would be, in a meaningful sense, a social network. Most of its value is bringing people together socially, and letting them communicate with their friends and make new ones. Putting everyone together into the same chaotic chatroom has less value than intelligently providing spaces where friends can hang out, as web-based social networks have proven.

In the case of a Facebook Metaverse that knows your friends and interests, server instancing could be made very intelligent: the software running behind the scenes could ensure that people always wind up in the same instance as their friends, or, if they don't have any in that space, with the group of people they're most likely to get along with. This option becomes more attractive in VR, where performance issues are hugely magnified and running servers with potentially thousands of extraneous animated characters (and their associated network load) may simply not be feasible.

4. You Won't Want to Do Everything In It

Not every activity you could possibly undertake makes sense in Virtual Reality. Most people may not ever go to work in the Metaverse. Virtual concerts probably don't make much sense, nor VR record stores. There's a reason we prefer Amazon and Spotify to actually trudging around physical stores, even when we live right next door to them. Virtual Reality is strictly worse for shopping than the regular old internet, most of the time.

The Metaverse is the ultimate candy for the architecture astronaut. 'It's a whole new world, man, we can do anything we want' and I fear that very much, because it's easy to make very, very bad decisions like that. [...] I don't think there's anything like a consensus on what people even want.

-John Carmack

That's not to say that these ideas have no value. Some virtual goods probably make sense to sell through VR. I've spent way too many hours making Isaac Clark walk the catwalk in his new armor in Dead Space 2 to believe that people won't enjoy playing dress-up in VR, and the sheer scale of the TF2 hat economy leads me to believe that people will pay money for the privilege.

Clothes can be sold this way, and maybe other virtual goods like vehicles and homes as well. I can also believe that people will pay to see movies in super-Imax in a private virtual theater with their friends, or to go explore meticulously designed online scenarios.

3. It's the Platform, Stupid

A big advantage of a Metaverse is its ability to reduce the barrier to entry to producing good VR content.

The Metaverse software can provide all the basics, and sell them to developers as a platform. Developers, rather than building stand-alone VR games, launched from the desktop, could buy or rent spaces in the Metaverse and build their VR content there as a service to users, monetized like an amusement park or a paintball course.

In order to support that, you'd have to provide the kind of tools that developers expect from game engines like Unity, and ensure that it all integrates nicely into the elements that make up the Metaverse backbone. Then, if you're a developer, you can build Metaverse content and take a bunch of things for granted. You can just assume that users will have avatars that they're comfortable in, and that the social mechanics work well. You can also assume that the VR implementation is high quality, and the engine is well-optimized. This removes a huge burden from the developer's shoulders, and that's a good thing. It also means that people can have faith that Metaverse content will have a certain standard of quality, and won't make them sick for unpredictable reasons.

A lot of the time that people spend in a Metaverse is going to be spent doing the kinds of things they do in online worlds today: playing competitive or cooperative multiplayer games. The value of the platform may be social, but most people, given a choice, will elect to do something interesting with their friends, rather than just sitting around. It's likely that a lot of the time that people spend in the Metaverse is going to look a lot like the time they spend in regular video games today: the Metaverse will just provide a deep social aspect to those experiences, and provide a platform for finding and using those games from within VR.

Neil Stephenson himself, in a retrospective interview, put it this way:

[T]he virtual reality that we all talked about and that we all imagined 20 years ago didn’t happen in the way that we predicted. It happened instead in the form of video games. And so what we have now is Warcraft guilds, instead of people going to bars on the street in Snow Crash... It’s just inherently more interesting to enter into an art-directed alternate world, where you can go on adventures and get into fights and engage with the world that way, than it is to enter a world where all you can do is kind of stand around and chat.

2. User Created Content is Important

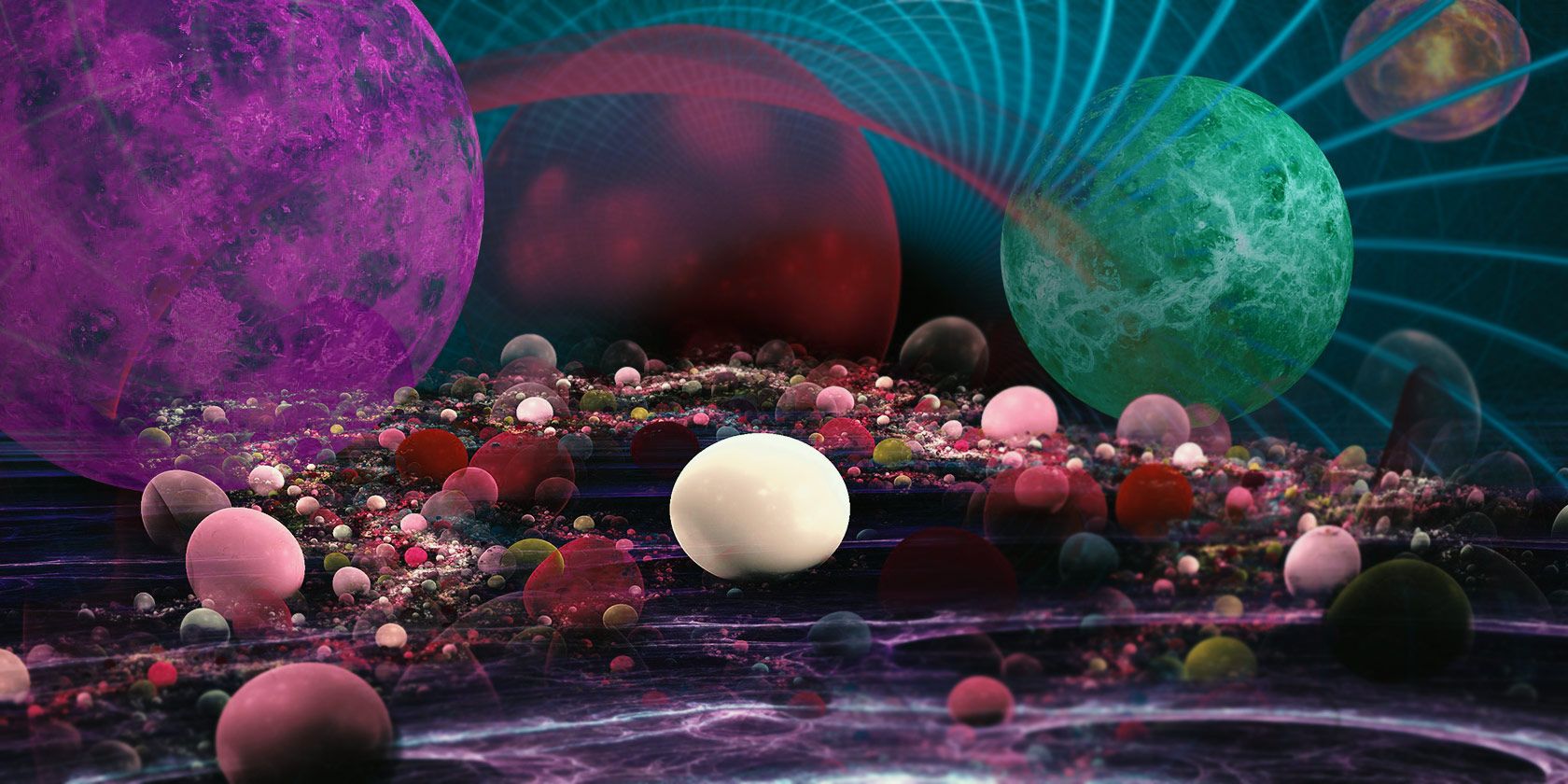

You may have heard the saying that you can't make more real-estate. In Virtual Reality, that simply isn't true. Virtual land is cheap, and there's no reason that space has to be consistent or even Euclidean.

You can teleport people at will and fit a planet into a shoebox, so there's no reason not to give users plenty of play space to make their own content. This can be done by providing gamified content creation tools like Minecraft or Spore or Little Big Planet, to make that content from inside VR in a user-friendly way. Those tools don't have to be as sophisticated as the ones you give to developers, but they should be easy to use. If creative multiplayer games and the Source modding community have taught the world anything, it should be that if you give people basic creative tools and turn them loose in an infinite space, they'll try their hardest to fill it.

Right now, one of the coolest experiences for Virtual Reality is called Minecrift. It's a user-created Minecraft mod that allows players to experience Minecraft content in VR, and it's great. The interface is re-thought to work in VR, the monsters are genuinely scary, and many of the spaces you'll explore are downright awe-inspiring.

The most compelling part, though, is being able to build big structures inside VR and then feel a sense of ownership over them as physical things. Virtual reality places and objects mean more, and if you can tap into that, it's a powerful way to tie users to your world and get them invested in their role in it. It also ensures that there will always be something fun to do in the Metaverse.

1. It Has to Be a Game First

One of the big problems that people run into when they try to build Metaverses is that they reach too far: they get too caught up in the dream, and fail to make sure that the product is actually fun and coherent. At its best, Second Life is a beautiful mess. Most of the time, it's just a mess. When you log on, the control scheme is a nightmare, the art looks like someone cramming a Dali print down your throat, and it's not at all clear what you should actually be doing, if anything. Then, you get yelled at by furries.

If the Metaverse is going to work, there has to be something fun to do even before other people start building their own worlds inside of it. The first user to log into the Metaverse should be able to have fun with high-quality, first party content, immediately understand what they're doing and how to do it, and then migrate smoothly to enjoying third party content as it's built. If nothing else, the Metaverse should do this so that third party developers have an example of what good game mechanics look like on the platform.

If you can't make good content for your platform, nobody else can either: eating your own dog food is mandatory.

In a lecture John Carmack gave on the Metaverse, he described the issue like this:

There's the danger of over-generality. You have projects like Second Life, which is in theory so interesting, and in practice, I tried it three times, to go and do something in Second Life, and I just can't make myself enjoy it. Whereas in games, they take it as their job to entertain you. [...] I think the better path is to identify the important, tactical things that you want to happen immediately, build the architecture around that, and hope that other things are going to be able to take advantage of that, rather than saying 'What about?' [...] Too many things fail that way.

Clearly, there's something to the idea of the Metaverse - it still catches peoples' imaginations after all these years, because, the bottom line is that it's offering people something that they really want. People want a world in which fantastic things are possible. People want to connect to each other without getting bogged down in details of geography. People want to be able to escape material realities and embrace the extraordinary.

The Metaverse is coming. It just might not look exactly like it does on TV. What do you think it'll look like? Share your thoughts in the comments section below!

Image credits: "Oculus Rift circa 1922", by Tony Buser, "Bonne Chance" by Cosette Panequem, "home sweet home" by Wyatt Wellman, "Winifred Holtby with Tweendykes - Orangery CGI" by BSFinHull, "Winifred Holtby with Tweendykes - Classroom CGI", "World of Warcraft" by SobControllers