Have you ever wished there was an "Undo" button for everything you do?

I certainly have. In fact, sometimes I catch myself trying to press Ctrl+Z while writing on paper.

Reverting your operating system to a previous state without consequences sounds almost like magic. You can quickly return to your work as if nothing happened, even when you don't know what caused the problem. That's why the System Restore feature is among the top things ex-Windows users want from Linux. Some go as far as proclaiming that Linux will never be as good as Windows because it lacks System Restore.

Those users should read the manual, or even better, this article, because today we'll present the tools that bring System Restore functionality to Linux. True, they're not always available by default, but neither is System Restore in Windows 10. You could also argue that they don't behave exactly the same as their Windows counterpart, but then again, the way System Restore works changed between Windows versions.

How Does System Restore Work in Windows?

The original System Restore feature dates back to 2000 and Windows ME (Millennium Edition). It could only restore system files and the registry, and it wasn't particularly reliable. Improvements arrived later, in Windows XP and Vista. Since then, System Restore relies on a system service called Volume Snapshot Service that can automatically create snapshots ("shadow copies") of the system -- including files that are currently in use -- and turn them into recoverable "restore points".

While this new approach offered more customization (users could allocate disk space for snapshots, and choose which directories should be monitored), it also brought limitations. System Restore snapshots work only with NTFS partitions, and in versions prior to Windows 8, they can't be permanent.

Each new Windows version introduced further confusion, because "Home" editions of Vista lacked the interface for restoring previous snapshots, and Windows 8 made it impossible to recover previous versions of a file from Explorer's Properties dialog. Finally, Windows 10 disabled System Restore altogether, leaving it to users to enable it manually. Most likely, this decision was intended to direct them towards Refresh and Restore.

But enough about Windows. Let's see how we can make this work on Linux.

How Does System Restore Work on Linux?

It doesn't -- at least not under that name. You won't find the feature called "System Restore" in your distro's menus. You'll have to find an approach that suits you and install the necessary applications. Most of them are based on the same principle as System Restore on Windows. They create snapshots of your system at specified intervals and let you roll back to a selected point in time.

Before diving into the apps, let's briefly explain what system snapshots are.

What's the Difference Between System Snapshots and Backups?

Semantics may vary, but generally speaking, backups are copies of files kept in a location separate from the files themselves. Backups rarely include everything on a disk; when they do, they're called disk images or disk clones. This type of backup "mirrors" the entire disk, including user data, the operating system, boot sectors, and more. Disk images can be used in the bare metal restore process, where you copy the contents of a hard disk onto a computer without an OS.

Snapshots, on the other hand, are saved states of a filesystem created at specific points in time and kept on the same storage device as the filesystem. They usually include all directories and files of a filesystem, or at the very least, the files required by the OS.

Keeping the snapshot in the same place as the filesystem makes it possible to perform a rollback, but it also saves disk space. In this setup, each new snapshot doesn't have to save the entire filesystem state. Instead, snapshots act like incremental backups and save only changes that were made since the last snapshot. This means that every snapshot depends on the previous one to fully restore the system. Conversely, a full backup or a disk image is independent of other backups, and can restore the system on its own.

The problem with snapshots is they're vulnerable to disk failures -- if your disk suffers severe mechanical damage, you'll likely lose the snapshots along with the entire filesystem. To prevent this, it's recommended to make a snapshot right after you install and set up your Linux distribution, and copy it to a separate storage device.

There are quite a few apps for Linux that can help you maintain system snapshots. Most of them are beginner-friendly and don't require advanced Linux skills. Take a look at our selection and pick the app that's best for your workflow.

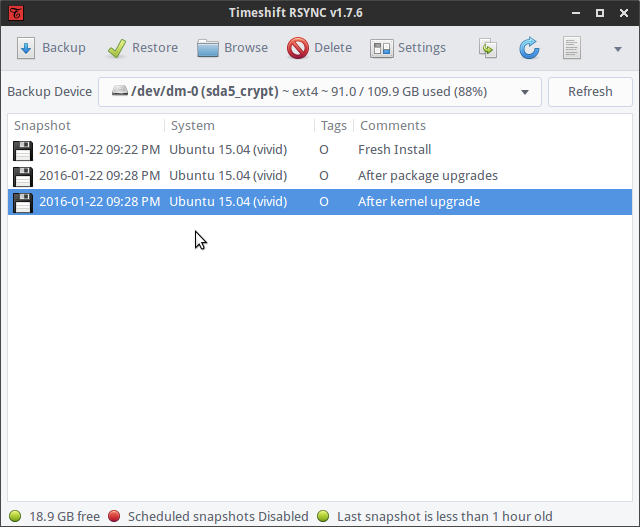

TimeShift

TimeShift has a simple graphical interface, and you can also use it from the terminal. By default, it doesn't include a user's personal files, but you can add custom directories to your snapshots. On Ubuntu and derivatives you can get TimeShift from the developer's PPA:

sudo apt-add-repository ppa:teejee2008/ppa

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install timeshift

while users of other distros can download the installer file and run it in the terminal:

./timeshift-latest-amd.64.run

There's also a version for BTRFS filesystems that supports the native BTRFS snapshots feature.

How it Works

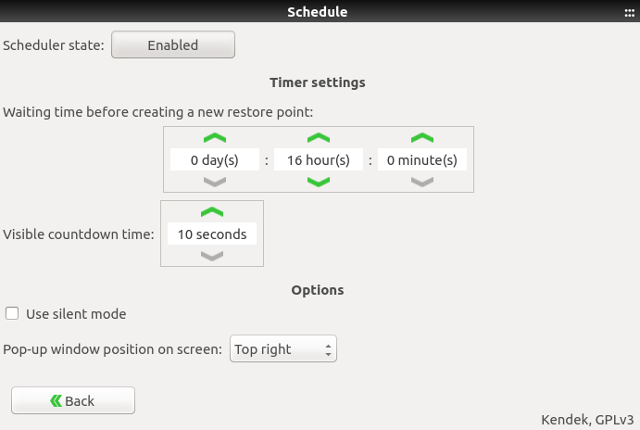

TimeShift lets you take snapshots whenever you want, or you can set it up to create them automatically. You can schedule hourly, daily, weekly, and monthly snapshots, and configure how often TimeShift should remove them. There is a special option called Boot Snapshots that creates one new snapshot after every reboot.

Restoring a snapshot with TimeShift is a straightforward process: you select a snapshot and choose the location to which it should be restored. TimeShift offers the option to restore snapshots to external devices, and the Clone feature can directly copy the current system state to another device. This is helpful for migrating your OS to a new computer without having to set up everything from scratch.

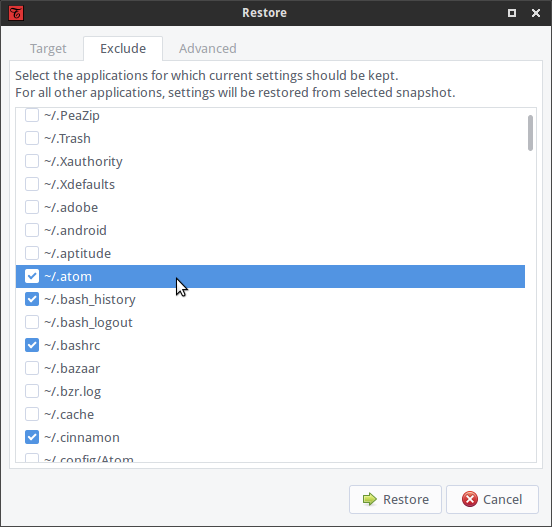

Before restoring a snapshot, TimeShift will ask if you want to preserve application settings, and let you choose which ones to keep. Remember that TimeShift requires GRUB 2 to boot into a restored snapshot.

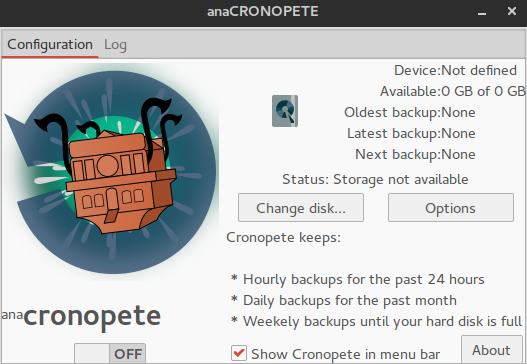

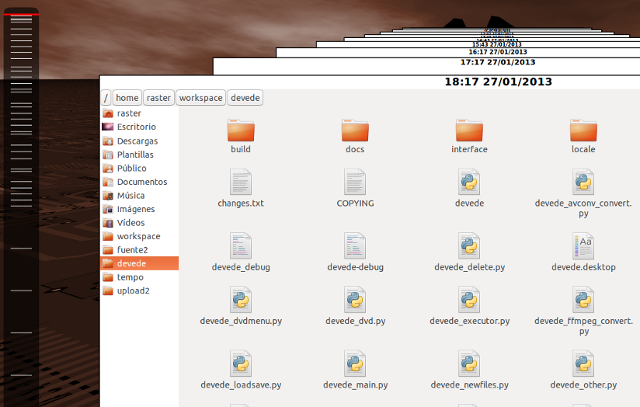

Cronopete

If TimeShift is simple, Cronopete is even simpler, at least in terms of appearance. It calls itself a clone of Time Machine for OS X, and works a bit differently than TimeShift. Cronopete offers packages for Ubuntu, Debian, and Fedora, while Arch Linux users can find it in the AUR.

How it Works

Unlike other apps on this list, Cronopete combines the backup and snapshot paradigms and forces you to keep snapshots on an external device. By default, it checks your files for changes every hour, but you can change the interval in the configuration dialog. If a file has not changed, Cronopete will only hard-link to it instead of copying the file, which helps save disk space.

Restoring files is probably the coolest thing about Cronopete. It lets you "scroll through time"; that is, visually browse all saved versions of your files and folders. To restore files, simply select them and click Restore. They will be copied from the external disk onto your current system. As you can probably deduce, Cronopete is not very practical for a full system restore, but it's a great choice if you want to keep multiple versions of individual files.

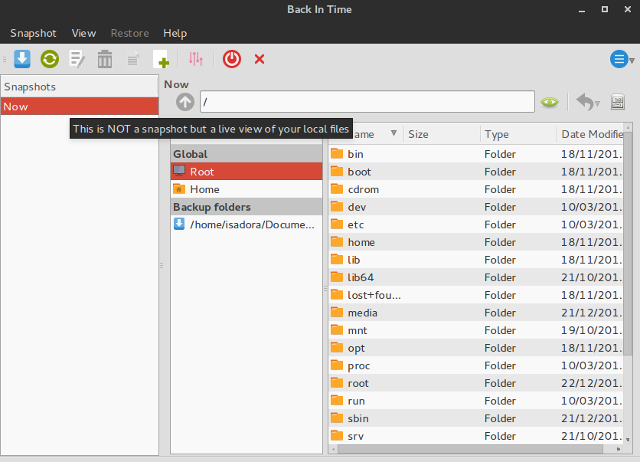

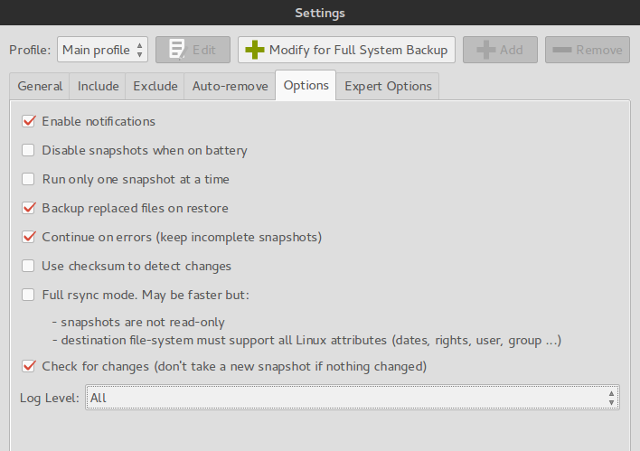

Back In Time

Back In Time looks user-friendly enough to attract Linux beginners, while its Settings dialog offers fine-grained control. The interface acts like a regular file manager, and you can preview all your snapshots, browse files in each of them, and restore selected files and folders.

Back In Time can be installed from a PPA if you're on Ubuntu:

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:bit-team/stable

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install backintime-qt4

Several distributions offer it in their repositories, and if yours doesn't have it, you can always download the source.

How it Works

Back In Time creates snapshots that include folders of your choice, but it can only restore those to which you have write access. Your snapshots can be encrypted and stored on a network device, an external disk, or your local filesystem. Back In Time updates only the files that have changed, and the Settings > Options tab lets you disable snapshots when no changes are required.

Snapshots can be scheduled (daily, weekly, monthly, several times per day, or only upon reboot) or you can create them manually by clicking the button in the main toolbar. The Settings > Auto-remove tab lets you define when Back In Time should remove old snapshots, and you can protect snapshots from deletion by giving them a name and selecting "Don't remove named snapshots".

Similar to Cronopete, Back In Time is more suitable for folder- or file-based rollbacks, but if you want to revert the entire filesystem, that's also possible. Restoring a snapshot is as easy as selecting it and deciding whether you want to restore just a few folders or the whole shebang.

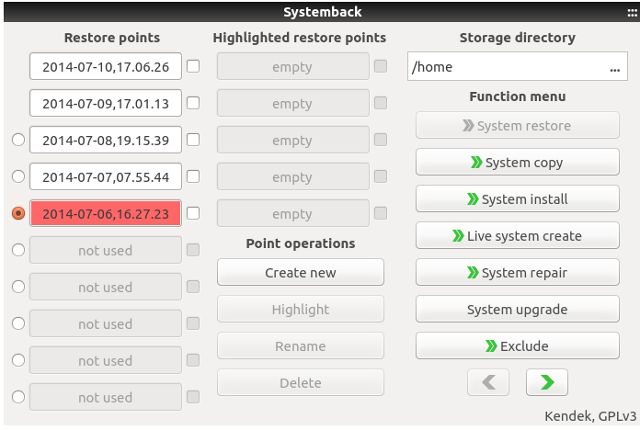

Systemback

Systemback packs an impressive amount of features in a tiny interface. Unfortunately, only users of Debian, Ubuntu, and its derivatives can play with Systemback for now, because there are no installation files for other distributions. The developer provides a PPA:

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:nemh/systemback

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install systemback

How it Works

Systemback isn't just another snapshot tool. It can turn your current system into a live CD or DVD that you can boot on another computer. It can fix or reinstall the GRUB 2 bootloader, and repair the fstab file. Still, you'll probably use it primarily for system snapshots.

Systemback limits the total amount of snapshots to ten, trusting you with the task of removing them. Snapshots can be incremental (only changed files are copied; the rest are represented by hard links), but you can disable this in the Settings dialog. When restoring files, you can perform a full restore or just copy the essential system files. Your personal data, such as pictures and documents, won't be included in the snapshots, but you can transfer them to a live CD with the Live system create > Include user data option.

Systemback lets you customize the snapshot schedule, but you're free to turn this off and create restore points manually. It's important to remember that Systemback doesn't support the NTFS filesystem, so you won't be able to restore a snapshot to or from a partition formatted as NTFS.

Snapper

Snapper is closely tied to openSUSE, where it was introduced in version 12.1. It's possible to install it on other distributions, but it's not guaranteed to work. The easiest way to set up Snapper is to install openSUSE on a BTRFS partition; in that case, Snapper gets automatically installed and configured. You can use Snapper as a command-line tool or through YaST, and there's an alternative called snapper-GUI.

How it Works

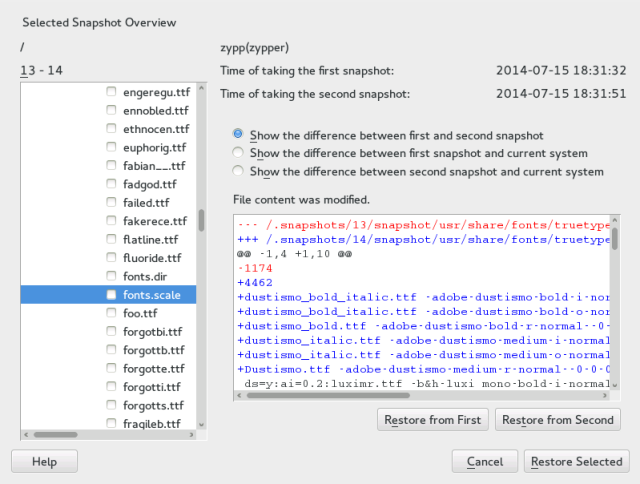

Snapper makes several different types of snapshots. Pre and post snapshots are made before and after installing new packages with zypper or YaST, and when you modify the system through YaST modules. That way you can compare snapshots and revert to the old state if the changes cause trouble. Timeline snapshots are created automatically every hour, unless you disable them. All other snapshots are called single, including those you create manually. Snapshots reside on the same partition for which they are created, and they grow in size, so keep that in mind when organizing your disk space.

By default, Snapper creates snapshots only for the root partition. To include other partitions and BTRFS subvolumes, you have to create a configuration file for each of them. This has to be done from the terminal. Make sure to run the command as root:

snapper -c CONFIGNAME create-config /PATH

Here -c stands for "configure", CONFIGNAME is the name you choose for the configuration, and /PATH is the location of the partition or subvolume. For example:

snapper -c home create-config /home

You can check currently active configurations with:

snapper list-configs

All configuration files are saved in

/etc/snapper/configs

, and you can modify them in a regular text editor. For example, you can disable hourly snapshots, toggle automatic snapshot removal, and tell Snapper how many old snapshots to keep.

The YaST Snapper module lets you create and compare snapshots. You can also roll back to a previous snapshot, as well as restore a previous version of a single file or a number of selected files.

An additional rollback method is provided by the package

grub2-snapper-plugin

for openSUSE. This lets Snapper boot into a snapshot and restore the system directly from the bootloader menu. If it's configured properly, there should be an option in GRUB 2 called "Start bootloader from a read-only snapshot". On other distributions you can try grub-btrfs to get similar results. Note that you can only boot snapshots created for the root partition.

How to Backup and Restore Installed Applications

Instead of reverting the entire OS, sometimes you'll just want to restore the software you installed. This is often the case with distro-hopping, reinstalling your current distribution, or upgrading it. Luckily, we can rely on these handy tools that simplify the app migration process.

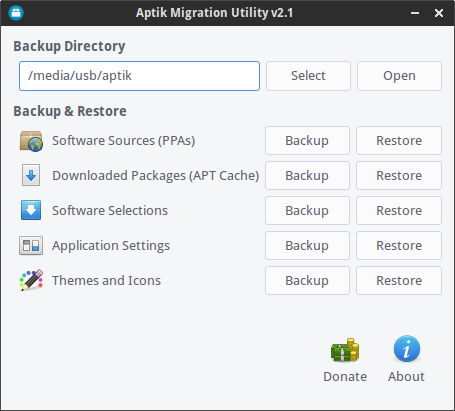

The first mention goes to Aptik, an application backup utility created by the developer of TimeShift.

It's only for Ubuntu-based distributions, and you can install it from the developer's PPA:

sudo apt-add-repository ppa:teejee2008/ppa

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install aptik

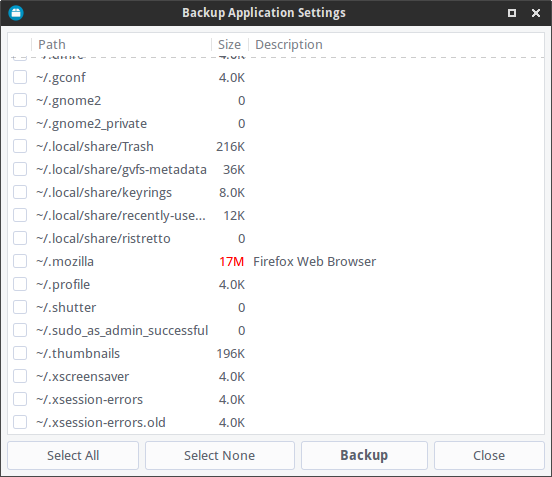

Aptik can export the list of currently installed packages along with the list of repositories you use and the downloaded packages themselves. There are also options for exporting application settings, desktop themes, and icon sets. Aptik categorizes the packages by installation type (preinstalled with the OS, installed by the user, installed automatically as dependencies, and installed from .deb files). It lets you drag-and-drop downloaded .deb files into the list to include them in the backup. You can keep the backup anywhere you want, and extract it to a freshly installed distribution by installing Aptik first and selecting Restore in the main application window.

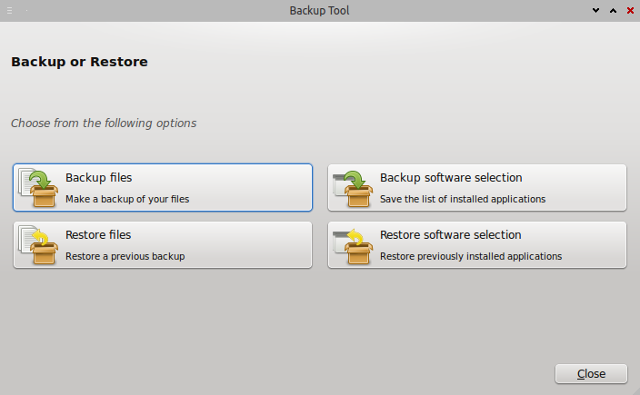

Linux Mint users can try Mint Backup Tool, which functions almost exactly the same as Aptik. Apart from restoring installed applications, this tool can perform a quick backup of a selected folder and its permissions.

Those who run Arch Linux can turn to Backpac. It creates lists of manually installed packages (both from the official repositories and the AUR) and can backup individual files of your choice. Restoring the system state with Backpac boils down to installing the exported packages, removing the ones that were not included in the snapshot, and overwriting the system files with their previously exported version.

Of course, there's a way to do all this without a third-party app, using only the tools provided by your package management system. On dpkg-based systems, you can export a list of installed apps with:

dpkg --get-selections > /home/yourusername/apps.txt

then copy that file along with repository information from

/etc/apt/sources.d/

and

/etc/apt/sources.list

to the new system. Provide the correct path to the apps.txt file, and migrate the apps to the new system with:

dpkg --set-selections < /path/to/apps.txt

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get dselect-upgrade

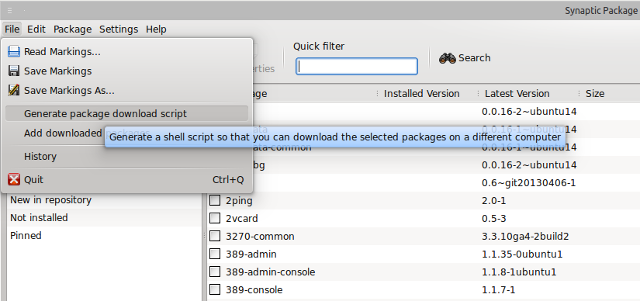

Some graphical package managers (Synaptic, for instance) can export and import lists of installed applications, so you don't have to do that from the terminal.

Advanced System Rollback Solutions

Perhaps the applications we've suggested so far simply don't cut it for you. The good news is that other solutions are available. Calling them "advanced" doesn't mean they're overly complicated; just that they might not be suitable for a beginner's first choice.

Rsnapshot [No Longer Available]

If you're looking for a quick way to take snapshots from the terminal, give rsnapshot a try. You can find it in the repositories of most Linux distributions. Rsnapshot keeps all its settings in

/etc/rsnapshot.conf

, and it's here you'll define the snapshot schedule, when to remove old snapshots, as well as which files and folders to actually include. Once you're happy with the configuration, test rsnapshot with:

rsnapshot configtest

rsnapshot -t hourly

to ensure everything runs smoothly. Remember that rsnapshot's configuration file requires tabs between options, not spaces, so don't move the parameters around by pressing the spacebar. There is no automatic restore feature, though, so you will just have to copy the files manually from a selected snapshot.

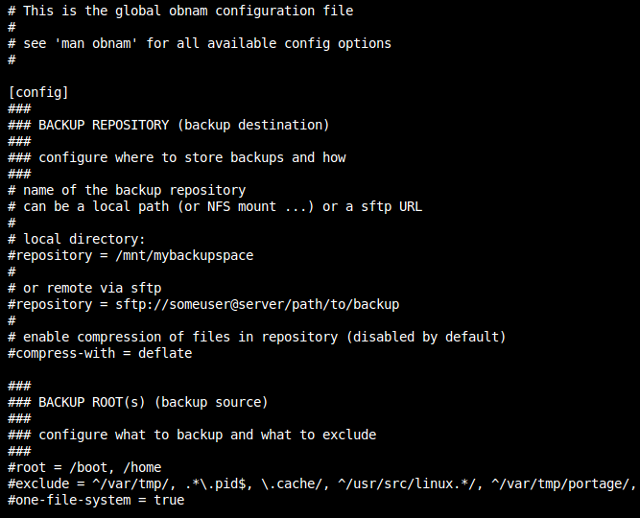

Obnam

Obnam is similar to rsnapshot, with some additional interesting features. First it creates a full backup of your system, then builds incremental snapshots containing only new and/or changed files. Your snapshots can be encrypted, and Obnam handles decryption automatically. The same applies to restoring your snapshots: there's a command for that, and Obnam lets you choose where to restore them.

You can include and exclude custom paths, and store your snapshots on a server or other remote location. Naturally, there's a way to remove aged snapshots, and the official user manual is a great piece of documentation that explains everything.

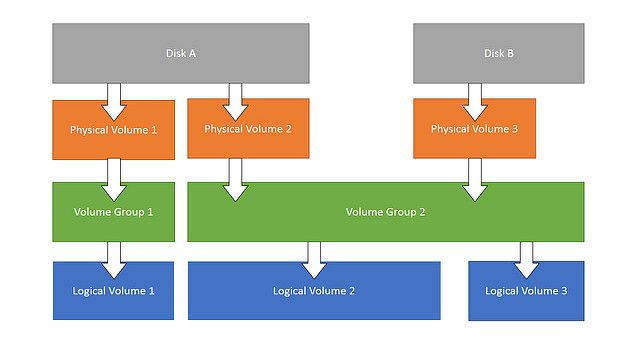

LVM Snapshots

When it comes to preserving precious data, it's always a good idea to think about it in advance. If you're just setting up your Linux system, it's worth considering LVM (Logical Volume Manager) as a way to organize your hard disks.

Why? Although it's not exactly an app, the LVM implementation in the Linux kernel comes with an in-built snapshot feature. You can mount the snapshots and browse them as any other disk or partition, merge several snapshots, and restore them to resolve system problems. Alternatively, you can use dattobd, a Linux kernel module that supports incremental snapshots of a live, running system without having to unmount partitions or reboot the computer.

As you have seen, you have many options to get the System Restore functionality on Linux, yet they're all technically very similar. Is there a better way to replace System Restore on Linux? Maybe it will be revealed in the future as these apps continue to develop, or maybe it hides in a combination of already existing tools.

What do you think? Have you used any of these apps? Would you agree that Linux needs something like System Restore? Join the discussion and share your advice in the comments.

Image Credits: An undo key from an old computer keyboard by stockmedia.cc, LVM Hierarchy by Linux Screenshots via Flickr.