The Golden Age of Animation brought us a treasure trove of cherished classics, many at the hands of Disney’s Nine Old Men.

How did this collective of artists revolutionize an entire industry? Many will tell you that it all started with a mouse, but we know better. Their real secret was a creative manifesto outlining the 12 ingredients that make great animation.

These 12 timeless principles are just as relevant today as they were at the time of their conception.

1. Squash and Stretch

Animators have no way of conveying the physical properties of a character or object other than through visual, on-screen cues. Many animators will tell you that good animation has less to do with the design and mannerisms of your characters, and more to do with how reactive their personalities and appearances are to what's going on around them.

Squash and stretch both tie into the tendency for animation to "cartoonify" reality. The "natural" motion of the ball bouncing off of the ground is exaggerated by the ball's "overreaction" to the barrier.

2. Anticipation

You're animating a scene that takes place at a public swimming pool. Your protagonist, a meek middle-schooler, is about to jump off of the high-dive for the first time. Chances are, this shy kid isn't about to just take a dunk without preparing himself emotionally first. All of these anticipatory considerations add a distinct richness to your world.

Your characters are now, suddenly, much more than generic automatons populating the scene. They know things. They feel things. They avoid pain and they gravitate toward that which delights them.

This prinicple, in many ways, has much more to do with the animator's ability as a storyteller than anything else. The key to anticipation is really in how the action is written.

3. Staging

Mise-en-scène is a term in the world of live-action film. It refers to the orchestration of on-screen elements and the way that the auteur uses this space to get his or her point across. The same consideration carries on spiritually here.

Crafting the geography of the frame with purpose allows you to guide the eye of the viewer, keeping their attention exactly where you want it. Everything needs to be expressed clearly, deliberately, and in a manner that they will be able to retain for later.

4. Pose to Pose vs. Straight Ahead Animation

Choosing between straight ahead and pose to pose animation will be one of the first technical decisions that you will need to make before beginning to figure things out. This dichotomy represents two distinct schools of thought.

The artist either charts out his or her course in advance, destination by destination, or simply starts from square one, exploring the action that he or she wishes to put down on paper without restraint.

Pose to Pose Animation

Let's say you're animating a woman hanging laundry on a clothesline, for example. In reality, there are no neat and tidy delineations that break this sequence down into portions.

An animator applying a pose to pose approach may start with one frame of the woman crouching down to pick up a shirt. The next pose may be her standing with the shirt held out in front of her.

Poses are added until all of the laundry has been taken care of, and she has retired for the afternoon. You have drawn only five or six frames, but the scene has already been authored to some extent.

Pose to pose animation is a great way to work if you're somebody who likes knowing what's ahead before setting out. These first few frames are known as keyframes. Traditionally, these frames would be drawn by the most experienced members of an animation team.

Once the entire production had been mapped out, junior-level assistants would fill in the blanks between each keyframe to link these landmarks together with action.

Straight Ahead Animation

Getting your character from point A to point B straight ahead-style will sometimes give you new, unexpected ideas. As you draw, sparks of creativity can revitalize action that may feel canned or mechanical if drawn pose to pose.

You're free to improvise and take a novel turn or two as you progress; you never need to worry about meeting something specific 20 or 30 frames down the line. If you're animating to music, you can mark each frame that the beat of the song falls on in order to coordinate the animation and give it rhythmic structure.

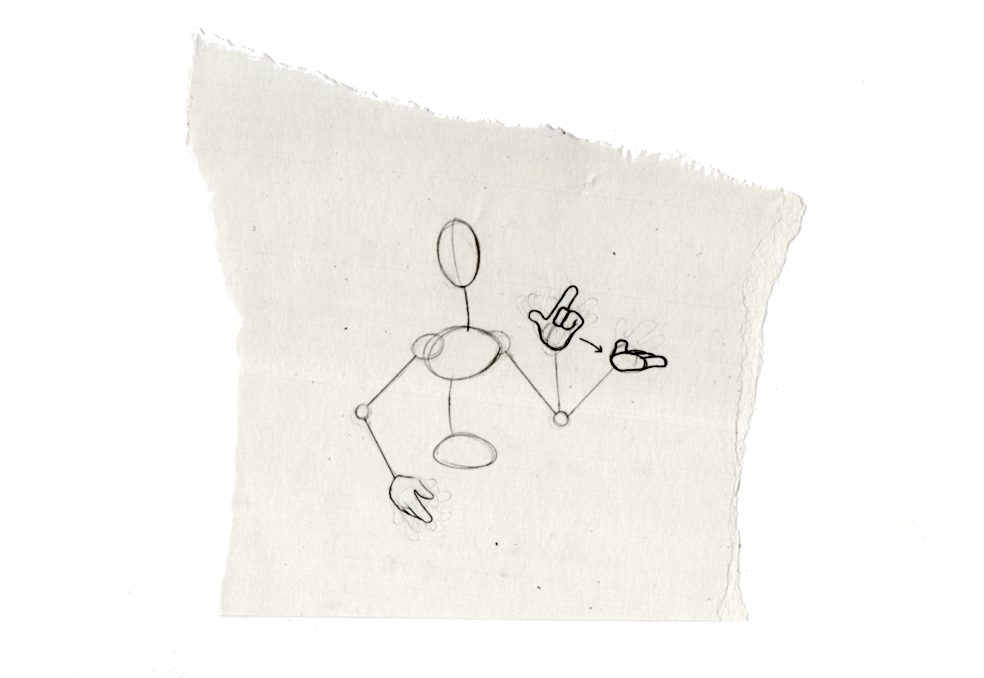

5. Overlapping Action and Following Action Through

When people move naturally, the weight of their limbs and how loosely they are associated with the trunk of their body will both be readily apparent. Mimicking this effect has less to do with creating action, and more to do with the way that your subject reacts physically after the action has transpired.

Without these added flourishes, the objects or characters that you draw may appear rigid and lifeless. If a beautiful woman's hair is lighter than air, it should float around her as she moves instead of hanging like wet spaghetti. Or, worse: not moving at all as she careens elegantly across the room.

6. Timing

As a storyteller, developing a sense of effective timing will not only make your work look and feel better—it will make your story more coherent, more impactful, and likely much easier for your audience to digest.

This category can be interpreted broadly. The physical attributes of each on-screen element should be characterized by the timing of its movement.

Also important to consider is how attuned your sense of dramatic or comedic timing is. You cannot give your audience more than they can chew on at once. Conversely, you also want to avoid boring them into submission with a lackluster frame or dead air. Balance is key. Engage them without overwhelming or confusing them.

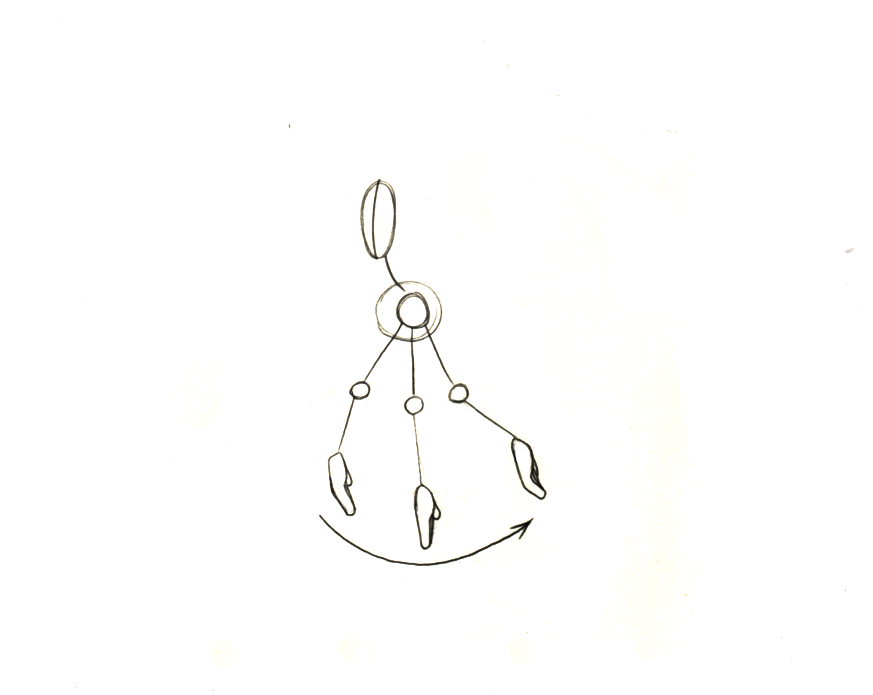

7. Arcing

Picture a kid throwing a ball straight up into the air. As the ball falls back down, it falls forward, according to the direction in which it was thrown.

After the ball has landed, stepping back and tracing its path through the air will reveal an upside-down curve. Objects bound by gravity travel in arcs like these whenever their movement challenges the laws of nature. Keeping this tendency in mind will enable you to plan patterns of movement that sell.

8. Secondary Action

The animator's lexicon is one riddled with subtle subconscious cues. When shooting in a live-action context, your leading lady's dress swings about her calves as she moves. This secondary action is exciting to the viewer. It keeps things moving.

Secondary action may also include emotional cues. Your character fiddles with their thumbs while trying to explain an unusual situation to a friend. They emote as they speak; each piece of secondary action should be an indicator of the character's internal state.

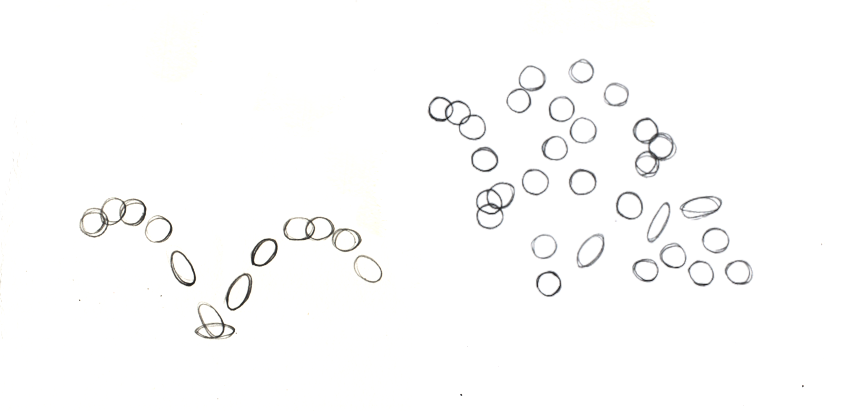

9. Slow In and Slow Out

This principle refers to the historical tendency for animators to "rally" their work around each pre-drawn keyframe, if utilizing such an approach. In essence, more frames are drawn around these keyframes than there are drawn further in between, which does two things for the audience.

First, it emphasizes each keyframe visually, as more time is spent transitioning in and out of these key poses than it is spent transitioning between them. Second, it reduces the time that the audience is left waiting between these much more narratively significant moments in time.

What people really want to see are all of the weird things that punctuate these brief lulls spent traveling from scene to scene.

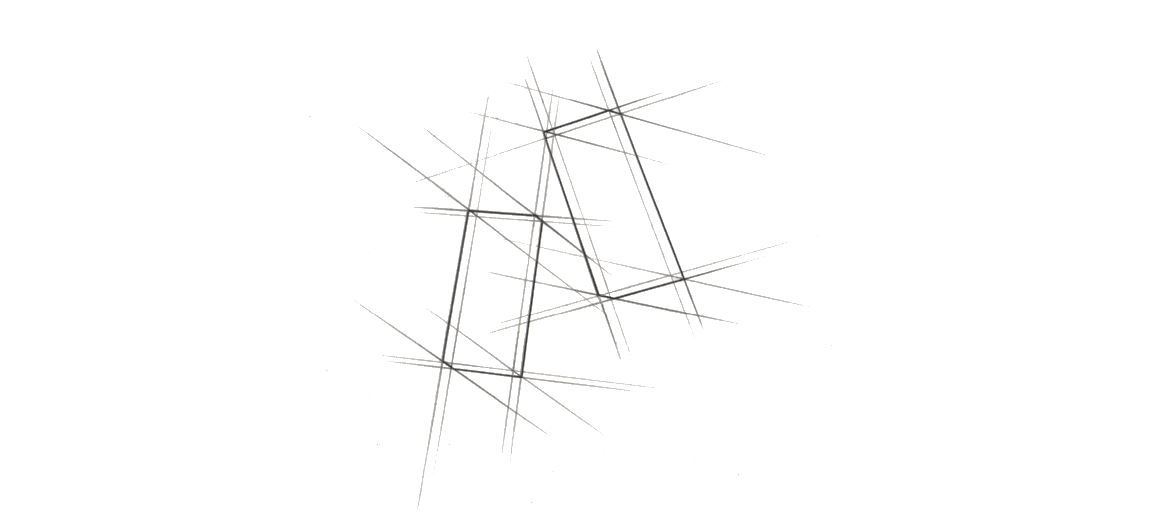

10. Solid Drawing

This will be hard for the avant-garde among us to hear, but your technical ability as an artist will play a significant role in how effectively you are able to convey action on-screen.

Beefing up on perspective, foreshortening, and even the principles of basic geometry keep each diegetic body rock-solid and completely consistent frame to frame (when your characters aren't too busy squashing and stretching, of course).

11. Exaggeration

Why do people like cartoons? What makes the medium more suited to some types of stories than, say, live-action or even a stage performance?

We turn to the world of animation when our vision goes beyond what can be done physically. When we have to draw everything in the scene from the bottom up, we end up with a lot of authority over how everything ends up looking, feeling, and playing out.

12. Appeal

As die-hard devotees of the Andrew Loomis School of Thought, we truly do believe that this part comes from you. Your skill level, your personal experience, and your passions in life will all play a vital role in how the loaf comes out of the oven, so to speak.

Appeal can be difficult to quantify; some claim that it's nothing that you can plan for. Most of us just throw ourselves at the wall until something starts to stick; there is no shame in the process.

Your art will surprise and delight you after you've been drawing for some time. All that you have to do is try.

Animation for Beginners: Where Do We Go From Here?

They say that every artist creates 10,000 terrible drawings before they really start doing their best work. Our philosophy: the sooner that you start, the better off that you're going to end up.

The 12 preceding points are all an awesome place for a beginner to start. The only way to become a truly great artist, however, is to practice earnestly and whole-heartedly every single day.

A doodle in the morning? A sketch session after school or work? Once you get the hang of it, it can be sort of difficult to put the pencil back down.