Have you decided that you want to use Linux? Great! You're joining a community of people who value sharing software and empowering others to get the most out of their computers. But as with any transition, some parts of your experience will require making an adjustment.

I don't believe Linux is any harder to use than Windows, but you do have to unlearn some behaviors in order to embrace new ones. Here are some things I've learned from years of using Linux that would have been great to know from the beginning.

1. Don't Install Linux on a Brand New Computer

If you have a new computer running Windows or macOS, you may want to wait a year or two before trying to install Linux. Trying to install Linux on brand new hardware is often more trouble than it's worth.

Most PC manufacturers don't bother checking to see if Linux runs on their machines. They're not selling the computers with Linux, and the overwhelming majority of their customers don't care. This often means they don't provide drivers for components that the Linux kernel doesn't yet support, and it's up to someone else to reverse engineer a solution. This takes time.

In some cases, you can't install Linux at all. In others, you may be able to install Linux only to later discover that the Wi-Fi doesn't work or the sound card isn't sending any audio through your speakers. Good luck trying to return a PC that you've wiped the original operating system from.

To play it safe, buy a PC that has been around for a few years. Check the Ubuntu certified hardware list if you want a glimpse at hardware guaranteed to work (if it works with Ubuntu, it likely works with other versions of Linux too). If you absolutely must have a new computer, buy one that comes with Linux pre-installed. You likely won't find these in retail stores, but there are plenty of options online.

2. Avoid Software From Outside Sources

On Windows, you typically head to a website and download an installer when you want new software. For the most part, Linux doesn't work this way.

There are too many versions of Linux for a developer to know which one to provide an installer for. Instead, users head to a Linux app store (filled with free software) or package manager to download what they want.

But there comes a time when the app you want isn't something your chosen Linux distribution provides. At that point, your only way to get that app is to install it from an outside source. Many Linux guides recommend you do this and walk you through the process.

Installing software from outside sources can lead to future problems. Sometimes an app requires a different version of a system component than the one your desktop provides. In order to work, the app comes with the newer version. Unfortunately, other programs on your machine may not yet be ready or compatible, leading to glitches or other hang-ups. Then you're left wondering why Linux is so buggy and are ready to switch to another operating system entirely.

This isn't guaranteed to happen. You can install quite a few apps from outside sources without incident, such as Google Chrome and Steam. But if things do start to get jittery, it can be very hard to figure out which install introduced problems. Even if you do detect the source, undoing the changes can be a challenge. Having software from a bunch of different sources can also block updates or cause an upgrade from one version of Linux to another to go horribly wrong.

A safer option is keep software from outside sources to an absolute minimum and try to stick to the software your distribution provides.

3. Use Software Made Specifically for Linux

If you're coming from Windows, you may not have given much thought to which operating systems a program is designed for. It may not have even occurred to you that a particular program can't run on every computer. Given that most desktop PCs run Windows, most applications are made with Microsoft's operating system in mind, even if they also support other options such as macOS and Linux.

When you first switch to Linux, you may want to stick to what you know. That means downloading the Linux versions of what you used to use on your old system. Unfortunately, companies often pour fewer resources into developing the Linux version. Skype, for example, until recently provided a Linux client that was years behind the Windows version.

It's not just a matter of missing features or bugs. Many people would say that Google Chrome is the best web browser available on Linux, but that doesn't mean it will integrate with the rest of your Linux desktop all that well. Mozilla Firefox is a free and open-source browser, yet it too looks more at home on Windows than Linux (at least initially). Fortunately, the situation with these two browsers is improving.

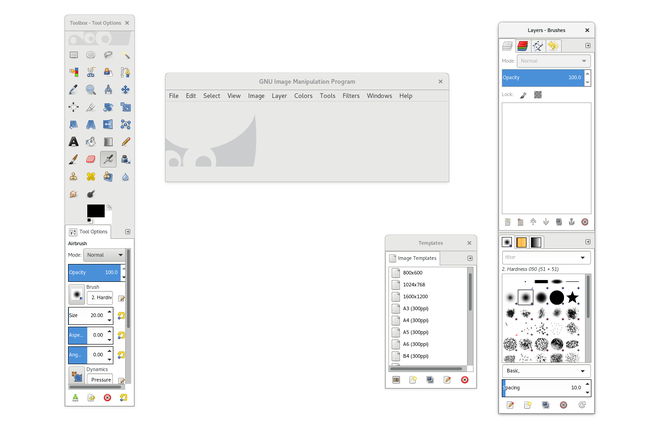

It's not that cross-platform software can't prioritize Linux or that going cross-platform is inherently bad. VLC is as great on Linux as it is elsewhere. Many free tools started on Linux before going to other platforms, such as GIMP and Pidgin. Software only on Linux isn't necessarily going to be good either.

But software made for Linux is likely to provide better experience than apps from developers who view Linux as an afterthought.

4. Be Open to New Experiences

Many Linux apps aren't the same as what you would encounter on Windows or macOS. They may perform a similar overall function, but they approach the task from a different way. If you insist on having a program that works exactly as the one you left behind, that can stop you from experiencing all that Linux has to offer.

The GNOME desktop environment is what you're likely to encounter on many of the most popular Linux distributions, and it's not quite like any other interface. I love the experience, which emphasizes searching for apps and content. Many GNOME apps also place a heavy emphasis on search, such as GNOME Music and GNOME Photos. Both are relatively simple apps, but they present your songs and images in an interesting way.

KDE software can seem complex at first, but if you dig around the settings, you can tweak them to look however you want. You may get so accustomed to having this level of control that using any other interface, on Linux or any other operating system, feels too restrictive! But you won't find this out if you don't first take the time to explore.

5. What You See May Be All You Ever Get

In the commercial software world, applications often undergo continuous iteration up until the point when a developer loses interest, and then the program goes away. With free software, changes often come more slowly.

Since there usually isn't as much money behind a project, developers can only devote so much time. People work when they can, and the contributors may change as different people gain or lose interest. Even when no one's interested, the code doesn't go away. Apps available from your Linux distribution can linger around for years without receiving an update.

This means that the app you've just discovered for the first time may not go through many changes in the foreseeable future. This is great if you love the interface exactly as it is and the program does everything you need it to. This is not so good if you run into a bug.

This situation isn't merely an issue of financial resources. The Linux ecosystem is relatively democratic compared to other computing environments. Teams have to build consensus to take things in a new direction, and since the code is open source, developers and users who aren't happy with a change can typically choose to keep things as they were. App developers have many desktop environments to support, and causing an app to integrate better with one can cause it to feel worse in another. Leaving things as they are may please the maximum number of people.

That's not to say that Linux software doesn't change. The GNOME desktop environment today looks and feels drastically different than it did ten years ago. Elementary OS and the curated software in its app store didn't even exist then. There's always something new coming. But if you're waiting for GIMP, Inkscape, or AbiWord to undergo a complete redesign, there's no guarantee that day will ever come.

Should You Still Use Linux?

Only you can answer that question. As for me, none of the issues above are deal breakers. I've adjusted my workflow to utilize apps only available for Linux, and I like knowing that I can install whatever I need from GNOME Software. Now that I bring in income working from my computer, I have even come to appreciate that many of the tools I use don't undergo regular changes.

When I need to perform a task, certain tools are consistent and dependable as ever. And when I want to try my hand at something different, there's always new software and themes to keep things fresh.

Are you a new Linux user? What are some of the surprises you've encountered? If you're a long-time user, what are some of the things you've learned that you wished you knew when you were first getting started?