The Internet of Things holds a huge amount of promise. Every device we interact with networked in some capability, bringing cheap smart home technology to everyone. This is only one of the possibilities. Well, unfortunately, as exciting as a fully networked world sounds, the Internet of Things is consistently and woefully insecure.

A group of Princeton University security researchers contend that the Internet of Things is so woefully insecure that even encrypted network traffic is easily recognizable.

Is there substance to their claim, or is it another "standard" IoT hit-piece? Let's take a look.

Baked In

The problem is that individual devices have individual security profiles. And some security settings come baked into the device. This means end-users are unable to change security settings.

Settings that are the same for thousand of matching products.

You can see the massive security issue this is.

Combined with a general misunderstanding (or is it sheer ignorance?) as to how easy it is to appropriate an IoT device for nefarious activities, and there is a real, global issue on hand.

For instance, a security researcher, when talking to Brian Krebs, relayed that they had witnessed ill-secured internet routers used as SOCKS proxies, advertised openly. They speculated that it would easy to use internet-based webcams and other IoT devices for the same, and myriad other purposes.

And they were right.

The end of 2016 saw a massive DDoS attack. "Massive," you say? Yes: 650 Gbps (that's about 81 GB/s). The security researchers from Imperva that spotted the attack noted through payload analysis that the majority of power came from compromised IoT devices. Dubbed "Leet" after a character string in the payload, it is the first IoT botnet to rival Mirai (the enormous botnet that targeted renowned security researcher and journalist, Brian Krebs).

IoT Sniffing

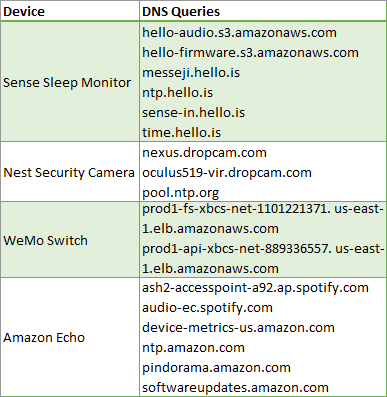

The Princeton research paper, titled A Smart Home is No Castle [PDF], explores the idea that "passive network observers, such as internet service providers, could potentially analyze IoT network traffic to infer sensitive details about users." Researchers Noah Apthorpe, Dillon Reisman, and Nick Feamster look at "a Sense sleep monitor, a Nest Cam Indoor security camera, a WeMo switch, and an Amazon Echo."

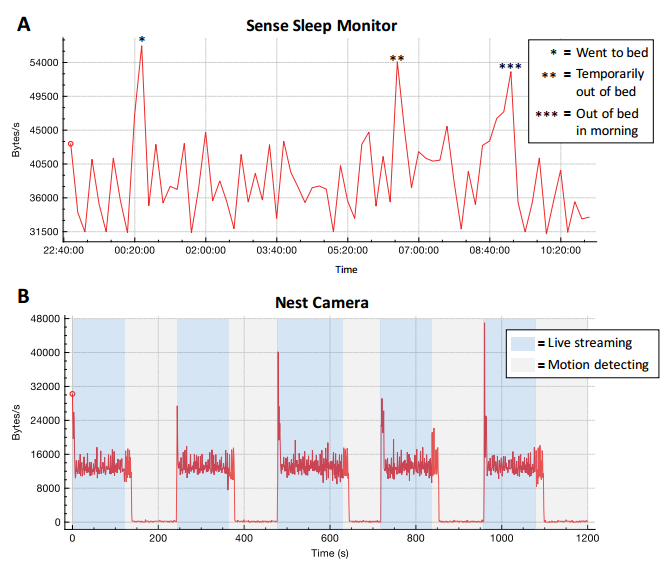

Their conclusion? Traffic fingerprints from each of the devices are recognizable, even when encrypted.

- Nest Cam -- Observer can infer when a user is actively monitoring a feed, or when a camera detects motion in its field of vision.

- Sense -- Observer can infer user sleeping patterns.

- WeMo -- Observer can detect when a physical appliance in a smart home switched on or off.

- Echo -- Observer can detect when a user is interacting with an intelligent personal assistant.

Access the Packets

The Princeton paper assumes an attacker sniffing (intercepting) packets (data) directly from an ISP. Their analysis comes directly from packet metadata: IP packet headers, TCP packet headers, and send/receive rates. Regardless of the interception point, if you can access packets in transition, you can attempt to interpret data.

The researchers used a three-step strategy to identify IoT devices connected to their makeshift network:

- Separate traffic into packet streams.

- Label streams by type of device.

- Examine traffic rates.

This strategy revealed that even if a device communicates with multiple services a potential attacker "typically only need to identify a single stream that encodes the device state." For instance, the below table illustrates DNS queries associated with each stream, mapped to a particular device.

The research results rely on several assumptions, some device specific. Data for the Sense sleep monitor assumes that users "only stop using their devices immediately prior to sleeping, that everyone in the home sleeps at the same time and does not share their devices, and that users do not leave their other devices running to perform network-intensive tasks or updates while they sleep."

Encryption and Conclusions

BII estimates that by 2020 there will be 24 billion IoT devices online. The Open Web Application Security Project's (OWASP) list of Top IoT Vulnerabilites [Broken URL Removed] is as follows:

- Insecure web interface.

- Insufficient authentication/authorization.

- Insecure network services.

- Lack of transport encryption.

- Privacy concerns.

- Insecure cloud interface.

- Insecure mobile interface.

- Insufficient security configurability.

- Insecure software/firmware.

- Poor physical security.

OWASP issued that list in 2014 -- and it hasn't seen an update since because the vulnerabilites remain the same. And, as the Princeton researchers report, it is surprising how easy a passive network observer could infer encrypted smart home traffic.

The challenge is deploying integrated IoT VPN solutions, or even convincing IoT device manufacturers that more security is worthwhile (as opposed to a necessity).

An important step would be drawing a distinction between device types. Some IoT devices are inherently more privacy sensitive, such as an integrated medical device versus an Amazon Echo. The analysis used only send/receive rates of encrypted traffic to identify user behavior -- no deep packet inspection is necessary. And while additional integrated security features may negatively impact IoT device performance, the responsibility lies with manufacturers to provide some semblance of security to end-users.

IoT devices are increasingly pervasive. Answers for privacy relation questions are not readily forthcoming, and research like this perfectly illustrates those concerns.

Have you welcomed smart home and IoT devices into your life? Do you have concerns about your privacy having seen this research? What security do you think manufacturers should be obliged to install in each device? Let us know your thoughts below!