The past few years have seen an explosion in the number of health and fitness apps -- from apps that track the number of steps you take in a day to ones that log the calories you eat to others that help you monitor specific medical conditions. Which means that there's a lot of health data now being collected by our devices.

Data that, along with much of the other information you generate, is being sold.

Your Health Data Is Valuable

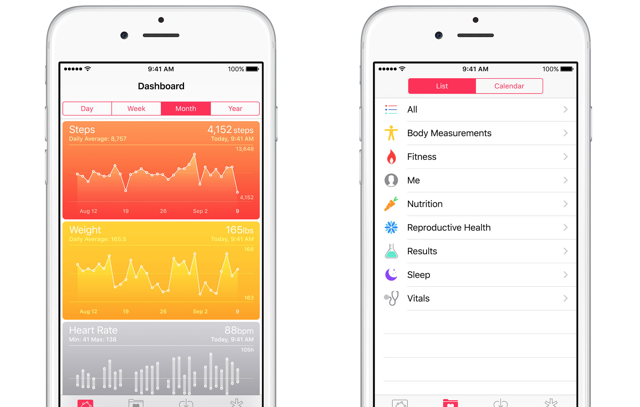

"Health data" is, of course, a wide-ranging term. What, exactly, qualifies as health data? It depends who you ask. For the sake of simplicity in this article, though, I'm going to use a very broad definition: everything from blood pressure measurements logged into Apple's Health app to the number of miles you biked and logged in MapMyFitness. The diet information you include in LoseIt! and the information you enter into Glow's fertility app fall under this category, too.

You'd be forgiven for thinking that all of this information is private and, for the most part, not that valuable. But like any other type of data, a lot of companies out there are selling it to make money. Marketing companies can make use of health data just like they can any other data -- to better target ads.

Let's say you were using LoseIt! on a regular basis in an effort to lose weight. A marketer could use that information to target you with ads about weight-loss products. Or you used MapMyFitness to log a hike in the mountains; you might start to see ads about outdoor clothing. If your next workout was logged as a bike ride, you could see cycling equipment advertised.

What about data for which you have a reasonable expectation of privacy? Like using a smartphone-based glucose monitor to keep track of your blood sugar? A marketer would pay a lot to find out that you're diabetic, as that puts you in a rather small market where you can be targeted very specifically.

It's not hard to imagine a lot of other situations in which your health data would be valuable to marketers. There's virtually no limit to the extent of ad targeting that ad networks will attempt.

Buying and Selling Your Health Data

Health data privacy and security are big issues -- it's something that the government is concerned about, and something that both state and private organizations keep a close eye on. Leaked private health data can have very serious consequences for people, and it's regulated with a proportional degree of oversight.

But the explosion of health apps has created a new opportunity for developers, marketers, and some members of the healthcare business, and they're not about to let that opportunity slip away. Before we get into that, though, there's a particular piece of legislation that's of importance to this discussion.

A Quick Note about HIPAA

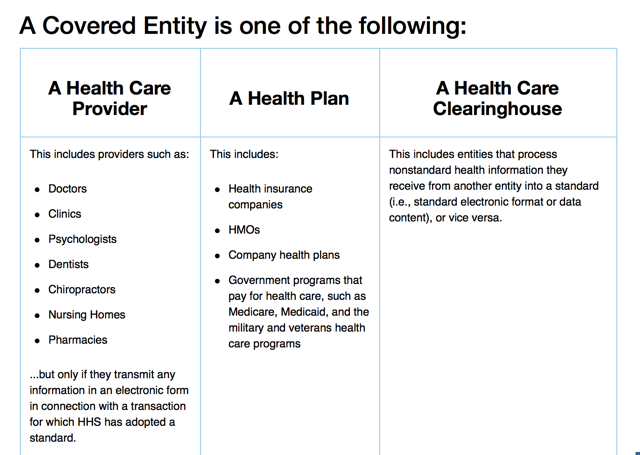

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is a complex piece of legislation that regulates the sharing of confidential health data -- you've probably signed a lot of HIPAA forms in your visits to the doctor's and dentist's office. The privacy rules set down in HIPAA govern the use and disclosure of data by "covered entities," which are healthcare providers, health insurers, and healthcare clearinghouses.

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, healthcare clearinghouses are defined as

entities that process nonstandard health information they receive from another entity into a standard (i.e., standard electronic format or data content), or vice versa.

The definition is rather nebulous, and could be interpreted in a number of ways, which leads to the ambiguity of health apps, the data they collect, and what they can do with it. And as data changes hands multiple times, it gets harder to keep track of how HIPAA might affect it.

Back to the idea of selling your health data.

Because app developers (as long as they're not affiliated with a covered entity) and marketing companies aren't covered under HIPAA, they can trade your health information without much fear of reprisal. So your health data is going to continue being sold to marketers, and there's not much you can do about it.

Can Insurers Buy This Data?

However, the issue that has a lot of people worried is health insurance providers. If your health data is out on the market, can health insurance providers buy it and use it to adjust your premium? It's no secret that insurers are mining massive amounts of data from a number of sources to try to make predictions about your risk level, and it certainly makes intuitive sense that they'd try to capitalize on the data generated by health apps, too.

Back in 2013, a study commissioned by the Financial Times found that the top 20 fitness apps, including MapMyFitness, WebMD, and iPeriod, were transmitting information to up to 70 different third-party companies, and stated that there was a chance that this information could end up in the hands of pharmaceutical and insurance companies.

Of course, "could" is an important word in that sentence. HIPAA may make that process difficult or impossible, depending on whether or not the information generated by these apps is considered protected health information or not. Information about "health status" is considered to be protected, but exactly what does that entail? Does your three-mile walk count as health-status-related information? It's hard to know.

With improvements in data analysis, it may not matter for long. There are all sorts of information that aren't protected by HIPAA, but could be extrapolated using algorithms to be useful to health insurance companies. If you post a lot on Facebook about partying, for example, a health insurance company could place you in a higher risk bracket because you're likely to consume more alcohol than average (much like credit companies are doing already).

Some commentators have brought up other sorts of issues that you should be aware of if you're using apps to store your health data. For example, if an insurance company buys an app developer, all of that data now begins to the insurer. Exactly how HIPAA would cover this is unclear, but it's a safe bet that a lot of that data would be put into their system.

An Evolving Issue

Because health apps are a relatively recent arrival on the app scene (at least at their current scale), the issue of how your health data is handled is one that continues to evolve. Who can buy and sell this data, what they can do with it, and what expectations you can have of your privacy are difficult to pin down at any given time, but what's clear is that your data is being sold -- definitely to data brokers and marketers, and possibly to insurers.

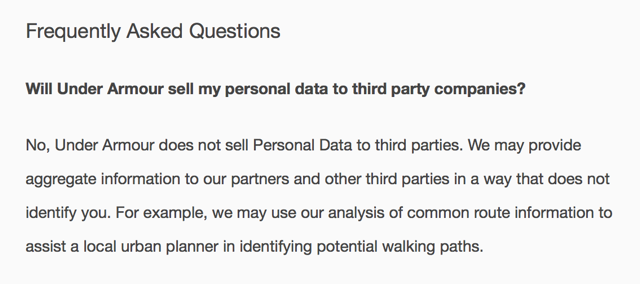

And don't be fooled by the "we won't sell your information" clauses in the privacy policy of those fitness apps. That often doesn't hold up, as transferring information between partners, trading assets, and other actions don't fall under the category of selling.

So we're currently in a strange sort of limbo -- a lot of this selling is going on, but we're not entirely sure who's doing the buying. We have a fairly reasonable expectation of privacy on this data, but we're also complicit because most users generally don't do much to look into the privacy policies (or permissions requests) of their apps. Might it be time to give up on these types of app and service in favor of old fashioned maps and math?

This issue isn't yet a hot-button one, but it's possible that we'll be seeing a lot about this in the near future as more people become savvy to the kinds of transactions that are being completed with information about their lives as the currency.

What do you think about health apps selling your data? Are you worried that companies could be getting more of your information that you're comfortable with? Or do you not care? Have you given up on trying to protect your personal data? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Image credit: Georgejmclittle via Shutterstock.