In the wake of the horrific terrorist attacks in Paris, there's been a great deal of discussion in the United States and around the world about data surveillance programs, their merits, and whether or not the public's greater awareness of these programs over the past two years enabled terrorists to fly under the radar in Europe leading up the attacks.

There's a lot of confusing information out there, and a lot of rhetoric flying back and forth from all sides, so let's talk through the issues to get everything straight.

What Did We Know Before the Attacks?

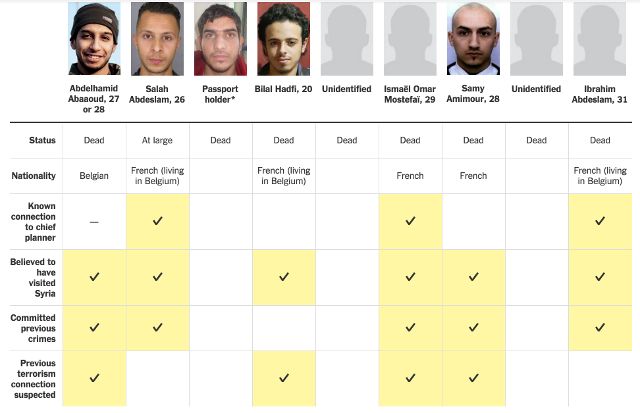

Because the attacks are still very recent, and some suspects are still at large, intelligence agencies haven't discussed in detail what was known before the attacks. However, according to a New York Times article, five of the nine men wanted in connection to the attacks had previously committed crimes, and four of them likely had connections to previous terrorist activities.

At least three of the attackers also have connections to Molenbeek, a well-known haven for extremists in Belgium, further suggesting that anti-terrorist organizations in Europe may have known who they were and that they could potentially be a threat.

In addition to this, there are reports that the French and German governments met a month prior to the attacks in response to reports that terrorists could be targeting France in the near future. It's also been reported that a car was stopped in Germany, the driver was arrested, and weapons were confiscated—both were likely related to the Paris attacks.

What does all this have to do with Edward Snowden? Let's jump to this week, and you'll see.

"A Lot of Hand-Wringing"

John Brennan, the current director of the CIA, has stated that the "hand-wringing" that took place in the wake of Snowden's revelations about mass surveillance led to international authorities missing important signs that the Paris attacks were being planned:

"In the past several years, because of a number of unauthorized disclosures and a lot of hand-wringing over the government’s role in the effort to try to uncover these terrorists, there have been some policy and legal and other actions that make our ability, collectively, internationally, to find these terrorists much more challenging."

James Woolsley, the former director of the CIA, says that Snowden has "blood on his hands" after Paris.

Jeb Bush, a Republican presidential candidate, thinks "we need to restore the metadata program," the NSA's collection of vast amounts of data on US citizens that is stored on government servers (the program is still active, though the data will be stored on phone companies' servers and accessible only by warrant starting later this month). Marco Rubio stated that "[T]he weakening of our intelligence gathering capabilities leaves America vulnerable."

Multiple Republican candidates have stated that they would increase surveillance in areas with Muslim populations within the United States. We haven't had time to see how mass surveillance comes up in the rhetoric of many of the candidates (especially the Democrats), but they're almost certainly scrambling to come up with new policy stances that will soothe the public's fear of terrorism on American soil.

A Closer Look

People are scared. And that's totally understandable. ISIS has proven that anyone can be a target, anywhere in the world, at any time. And that's really frightening. But we need to be very careful about how we respond to this threat. There are a lot of different ideas that people are throwing around about surveillance, and we'll go through them one at a time.

To get started, let's break down the idea that more mass surveillance will help prevent future attacks like this.

First of all, mass surveillance means that an organization will be collecting data on a huge number of people at all times. People that aren't currently suspects or under suspicion of being connected to terrorist cells. People like your neighbor, your mom, your kids' teacher. Is that where you want governmental resources to be spent?

Or should it be spent on people who are already under suspicion of being connected to terrorist organizations? The people who were involved in the Paris attacks were already in the government's top-secret S files, and the French authorities still didn't see the attack coming. Monitoring the cell phone metadata of the rest of their citizens wouldn't have helped.

This is the kind of monitoring that many Republicans in the United States are currently calling for. And while I have no problem with careful monitoring of terror suspects, I'm confident in saying that increased mass surveillance isn't going to help. In fact, it could hinder our attempts in trying to identify potential terrorists.

According to Glenn Greenwald, the NSA is collecting so much data that it doesn't even know what it has in its archives. Should our analysts be sorting through billions of points of data on all of our citizens or just focusing on those who have ties to terrorist organizations?

Second, the idea that encryption is what kept authorities from discovering the attack plans. This hasn't been specifically stated, but it's likely to be implied in the coming months during discussions of how we can prevent another attack like this.

Some politicians have already come out saying that they'd like to ban or restrict the use of encryption, and their voices are generally joined by others after events like the Paris attacks. But when you hear someone using this line of reasoning, remember that terrorists don't just encrypt their data and instantly become invisible to intelligence agencies. There's a lot more to it.

Also, remember that metadata collection works whether communication is encrypted or not. So if a politician talks about using programs like the NSA's metadata collection to combat terrorists' use of encryption—as they undoubtedly will—don't be fooled by their conflation of the issues. Metadata is good for creating models of communications networks, but that's not going to indicate that an attack is forthcoming. The content of a message is still hidden.

And finally, let's talk about Edward Snowden. Brennan, Woolsley, and many others are saying that Snowden's revelations directly or indirectly led to this attack. Glenn Greenwald, as usual, puts it better than anyone else could:

"One key premise here seems to be that prior to the Snowden reporting, The Terrorists helpfully and stupidly used telephones and unencrypted emails to plot, so Western governments were able to track their plotting and disrupt at least large-scale attacks. That would come as a massive surprise to the victims of the attacks of 2002 in Bali, 2004 in Madrid, 2005 in London, 2008 in Mumbai, and April 2013 at the Boston Marathon. How did the multiple perpetrators of those well-coordinated attacks — all of which were carried out prior to Snowden’s June 2013 revelations — hide their communications from detection?

"This is a glaring case where propagandists can’t keep their stories straight. The implicit premise of this accusation is that The Terrorists didn’t know to avoid telephones or how to use effective encryption until Snowden came along and told them. Yet we’ve been warned for years and years before Snowden that The Terrorists are so diabolical and sophisticated that they engage in all sorts of complex techniques to evade electronic surveillance."

There are a lot of ways that terrorists can communicate that wouldn't set off the government's metadata alarms. Disposable cell phones, communication through gaming forums (a medium that has reportedly been used in the past), USB sticks, and a variety of other methods that don't require regular, patterned cellular communication are out there. And at least three of the Paris attackers lived in the Molenbeek neighborhood, and a number of them frequented a bar there; there's no reason they couldn't have just communicated in person. These methods and others like the have been used for decades, not just since 2013.

Did Edward Snowden's revelations cause the Paris attacks? No. Did they make the attack more likely to succeed? No. Did they alert terrorists to the fact that they were being monitored? No. Don't fall for any of this nonsense.

So What Should We Do?

Of course, we're faced with a very serious issue here. How do we prevent another attack like the one we saw in Paris? I'm confident that increased mass surveillance isn't the way to go. Increased scrutiny and continued monitoring of people with ties to terrorist organizations seems like a good start. And the discontinuance of the NSA's metadata program would probably help, too, by concentrating the data that our analysts need to go through.

But beyond that, it's anyone's guess. De-radicalization efforts, increased border scrutiny, refugee screening, and dozens of other strategies have been suggested, and each has its merits. You'll likely cast your vote on which of these you think is the best idea during the next major election in your country, and I hope this article has been helpful in showing you that many issues are being conflated and used to push intelligence-gathering agendas, even where they wouldn't be useful. Please continue thinking critically.

This is a serious issue with grave consequences, and I sincerely hope that we find a good strategy for dealing with it. Until then, though, it's all up in the air.

What do you think about politicians' reinvigorated calls for surveillance and the restriction of encryption? Do you think these strategies would help in the fight against ISIS and other terror organizations? Where do you draw the line between personal privacy and national security? Share your (civil, conversational) thoughts below!

Image credits: The New York Times, scyther5 via Shutterstock.com.