As Twitter struggles to address a rampant abuse problem on the social media network, it has brought another well-argued issue back to the surface. Should publications be allowed to embed your public tweets without permission, especially when those tweets might open you up to aggressive trolls? As social media continues to be a source of growth and frustration for the field of journalism, this is just one more question to add to the list of concerns over the spaces where social media and journalism intersect.

I recently came across a series of tweets, which for reasons that will quickly become apparent, I won't be sharing here. It was a tweet directed at Mic for publishing a story about Twitter users reacting to a racist headline in a post on Facebook about a Chinese Olympic swimmer. Still with me?

The "Twitter reacts" genre of articles, for better or worse, have become a staple of many online publications, as the social network has become a great way to gauge a portion of the public's reaction to any given event.

In this case, however, one person, upon seeing his tweets used in this manner, was not happy. He criticized the magazine for embedding one of his tweets in which he condemned the original racist headline, and argued that Mic should not be able to share the tweet without asking permission or without paying him. He added that the use of the tweets exposed him and other people of color to abuse from people who might not have seen his thoughts otherwise. He called on the magazine to delete his tweet, along with those of two other people used in the article. If the magazine wanted to write about the story, they should reach out to people on Twitter and ask them if they're interested in writing about the racist headline.

While the magazine did not respond on Twitter, it appears to have complied and removed the tweets. Beyond a brief note at the bottom of the piece that reads, "This story has been updated," there is no indication on the Mic website of what transpired.

So should online magazines and website be allowed to publish a tweet in an article without permission?

It's Already Public

In a black and white world devoid of nuance, the answer is, unequivocally, yes. Unless you have a protected account on Twitter, any assumption that you should be afforded some sort of privacy is illogical.

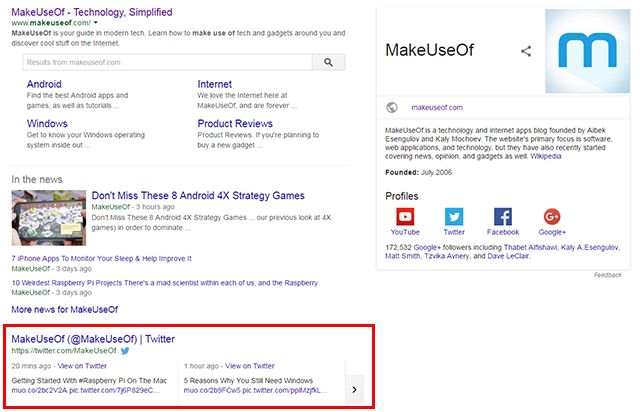

Even if you try to fly under the radar by not using hashtags, that just doesn't matter anymore. Your tweets will still show up in Twitter's search results, and beyond. Tweets can also show up in Google search results, as can your Twitter profile, the latter even if you have switched from a public to a protected account.

The Twitter user in question had under 100 followers at the time, and so his argument that a popular online magazine using his tweets could bring some unwanted attention is understandable. Except that, just as that one intrepid journalist was able to find his tweet, so would others. Had that journalist chosen to retweet him to her hundreds of followers, it would have had the same effect. If one of her followers, and their thousands of followers had retweeted it…you get the point.

Twitter, by its very nature, is a public platform. It's malleable enough that people use it for varied reasons. Some don't tweet at all, using it only to consume information. But once you put a tweet out there, whether you have 5 or 500 or 5,000 followers, it's in the public eye.

It's much like the argument used by people in public who bristle at having their photo taken by a stranger without permission. While laws can vary from country to country, in the United States, you can take a photo of a person in public without their consent, within reason. Photojojo sums it up perfectly:

People can be photographed if they are in public (without their consent) unless they have secluded themselves and can expect a reasonable degree of privacy. Kids swimming in a fountain? Okay. Somebody entering their PIN at the ATM? Not okay.

Tweeting in public is much the same. Expecting a reasonable degree of privacy on Twitter equals using a protected account where your tweets can only be seen by people you have approved to follow you.

Twitter's Own Stance

Twitter has pretty strict guidelines on how you can use content generated on the site. An attempt by one site to archive deleted tweets originally posted by public personalities such as politicians and celebrities was shortlived.

In July 2016, Post Ghost received an email from Twitter informing them that their use of the Twitter API was in violation of their Developer Agreement. According to that agreement, third parties cannot display tweets that have been deleted by users. Twitter similarly shut down Politiwhoops and its sister sites in 2015 for the same reason.

On the other hand, Twitter very much allows the embedding of tweets on third-party sites, providing the code that enables that feature, and services like Storify are built on the very concept of curating content from social networks.

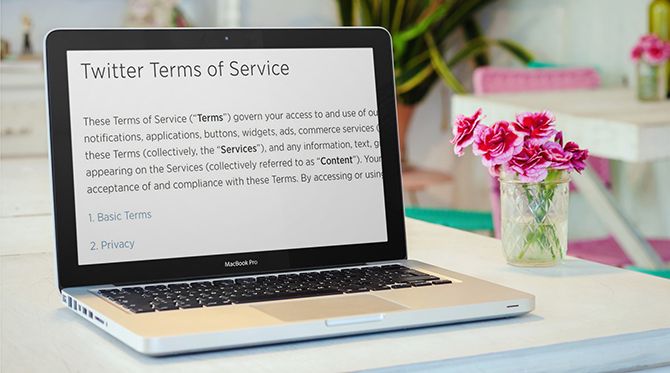

In fact, Twitter's Terms of Service that any Twitter user has agreed to by signing up for the service clearly states:

Most Content you submit, post, or display through the Twitter Services is public by default and will be able to be viewed by other users and through third party services and websites ... You should only provide Content that you are comfortable sharing with others under these Terms.

The caveat of "most content" rather than "all content" (as it used to read) is likely due to Twitter having to withhold tweets in certain geographic locations.

The TOS continues:

You retain your rights to any Content you submit, post or display on or through the Services. By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed).

Twitter goes one step further and puts that part of the TOS in layman's terms:

This license is you authorizing us to make your Tweets on the Twitter Services available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same.

The TOS keeps going on:

You agree that this license includes the right for Twitter to provide, promote, and improve the Services and to make Content submitted to or through the Services available to other companies, organizations or individuals who partner with Twitter for the syndication, broadcast, distribution or publication of such Content on other media and services, subject to our terms and conditions for such Content use.

Such additional uses by Twitter, or other companies, organizations or individuals who partner with Twitter, may be made with no compensation paid to you with respect to the Content that you submit, post, transmit or otherwise make available through the Services.

What this all boils down to is, legally, like it or not Twitter and any media outlet or website that chooses to embed your tweets has the right to do so, without first asking permission. And by agreeing to use the free service, you are agreeing to each word of its TOS.

Copyright Infringement

It's easy to look at Twitter's TOS, and the reality of a searchable web, and say, any expectation of privacy is unfounded. Even from a copyright perspective, the magazine was perfectly within its right. For example, in 2013, a jury awarded $1.2 million to a photographer after his photo, which he shared on Twitter, was published in print by AFP and Getty Images. Had the photos been embedded, on the other hand, they would have, legally speaking, been perfectly within their right, as is pointed out by BuzzFeed.

Don't believe BuzzFeed? The Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), a product of a leading authority on journalistic ethics, the Columbia Journalism School, agrees with BuzzFeed. In a CJR article on copyright issues in the age of the internet, the author comes to the conclusion that embedding content (from Twitter as a specific example) is acceptable because no copy of that content has been made. Taking a screenshot and posting it on your site, however, could be seen as a copyright violation.

Exceptions to the Rule

Some journalists do go the extra mile and reach out to Twitter users for permission. This very issue was a heated topic of discussion a few years ago when BuzzFeed published a piece embedding tweets by rape victims, in which they shared what they had been wearing when they were attacked. Their tweets were in response to a question by one Twitter user asking them to share this information. The Buzzfeed journalist proceeded to ask all who shared their personal stories if she could embed their tweets, and they agreed. (The identification of rape victims by the media without their permission is recognized as a red line.) She did not, however, ask permission from the woman who posed the question in the first place, and who in those embedded tweets, did not share personal details and did not identify herself as a victim. This story, which gained widespread coverage at the time, was complicated due to the nature of the topic, and the recognized code of ethics when reporting on rape survivors.

So should there be other exceptions? In the case of the tweet I saw, for example, the question of racism was broached. If embedding a tweet, and by extension, the identification of that person, opens them up to bigots or trolls, should journalists first ask permission? While Twitter's search function is far more reliable than it used to be, does that justify the risk of exposing an individual to hateful threats when these tweets are shared on websites that receive tens of thousands of hits a day?

This brings us to the real question at the heart of his tweets, which Twitter has yet to resolve -- how can they successfully combat abuse on the social network? A very public example of how Twitter tackled racist abuse was seen when comedian and actress Leslie Jones came under vicious and racist attack by a legion of trolls on Twitter, at the bidding of the conservative and controversial editor Milo Yiannopoulos. Twitter moved to permanently suspend Yiannopoulos.

In the case of risking racist vitriol when your opinion is seen by others, the expectation should not be that magazines and websites should not be allowed to embed your tweets. The expectation is that Twitter should be able to successfully combat the ability of trolls to attack Twitter users -- whether they have 100 followers as this man did, or the 550,000 followers Jones has.

By calling on the journalist not to embed the tweets, we are effectively putting an end to useful dialogue. Rather than ask journalists not to report on important issues, whether that's by going out and speaking to people, or by finding valid opinions that have been shared on Twitter, we should be asking Twitter to improve its ability to prevent abuse on its platform.

Do you think publications should have to ask before using tweets in their articles? Let us know in the comments.

Image Credits: PlaceIt, Enzonzo via Shutterstock.com