An alarming New York Post article has stirred up a hornet’s nest by suggesting that Hulu will be slowly moving towards a business model that requires authentication. In other words, users who want to watch certain content – or perhaps any content – will have to prove they’re already a cable subscriber.

This move is not unprecedented. A limited version of it is already in place for FOX content on Hulu, Comcast is working on its own streaming service for cable subscribers and HBO GO has used this model from day one. I think it’s something that we may be forced to put up with – and here’s why.

The Thrashing Giants

Geeks love to act a bit smug about how they’re changing media through piracy, digital distribution and “voting with my wallet.” Pricking giant corporations is fun, but eventually they begin to thrash around - and sometimes, they hit something.

Both broadcasting networks and service providers are raising a huge fuss. Unlike the RIAA in the early 2000s, which seemed to be bewildered and confused by the rise of digital music, today’s networks and service providers are very aware that their business model could be rendered obsolete if people were allowed to have inexpensive, easy access to a wide variety of content.

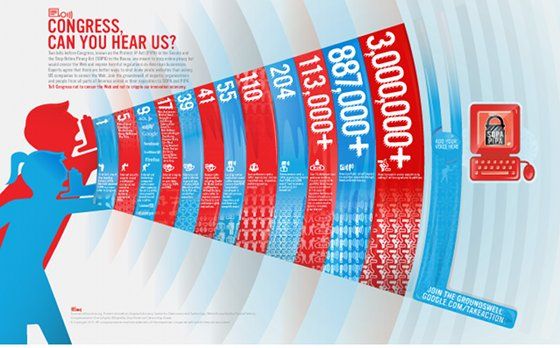

And they’re striking back on a variety of levels. Yes, nerd rage managed to stop SOPA, but a new, similar bill is likely to be purposed in the future. Meanwhile, little has been done to stop other moves that are bad for consumers. The merger of Comcast and NBCUniversal was approved without much opposition and all major networks are increasingly hesitant to make content available for streaming. Which brings us to the next point.

Digital Video Is Not Digital Music

A major advantage the digital revolution had against the music industry was the low cost of producing music. Pop stars are million-dollar projects, but a talented person with a guitar and a studio carved in the back of a warehouse can also create someone people will listen to and make money from it. Also, a band can always make money by touring, which has become the main revenue stream for most of today’s artists.

Video is different. The vast majority of content – and certainly all highly profitable content - is produced and owned by very large organizations such as NBCUniversal, CBS and Time Warner. Though they employ talented artists and actors, it’s nearly impossible for the talent to leave and form their own successful enterprise. Creating an original show or movie with the polish demanded by most viewers is an expensive endeavor. A budget of a few million to make (and promote) a motion picture is considered hopelessly small. Only documentaries can consistently turn a profit on that kind of cash.

Even if some talented people do make a great film on their own, they have to distribute it, which means – that’s right! – negotiating with major networks. Going straight to the web is conceivable, but it means spending an outrageous amount of time chasing the hope of profits that a major blockbuster film or popular TV show will exceed within an hour of its release.

Striking a deal with Netflix is now a possibility, as shown by the re-incarnation of Arrested Development and the introduction of other original content. But Netflix has its own financial troubles, most of which are caused by the fact that a few companies hold rights to all the content most people want. Netflix can’t put anything on the service unless the networks that own content play ball – and the cost to gain access to such content is constantly rising.

Forget user anger about pricing. The real threat to Netflix is the possibility that all major networks will simply wave goodbye, leaving the service with no headline content and no profit to pay people producing original content to be sold to Netflix.

They Want The Tubes, Too

The .MP3 was key to digital music. Music files burned of CDs were huge (relative to the storage capacities of the day) which made them hard to share. It was only the introduction of the .MP3 that made digital music something people could put on thumb drives or share online, even when connected via a measly 56 Kbps modem or a 1.5 Mbps DSL network.

Online video has yet to receive its MP3. Video files are massive. Downloading a high-resolution video is a day-long process for most people in rural areas of developed companies and almost everyone in the developing world. Even a standard-definition movie can take several hours.

This means that viewing large quantities of video, legally or illegally, is something only people with a lot of bandwidth can enjoy. And who owns that bandwidth? Often, it’s companies with a vested interest in protecting content. Comcast, which is infamous for its multiple attempts to cap bandwidth or restrict the bandwidth and also owns a majority stake in NBCUniversal, is the only viable choice for large portions of the United States.

Even companies that do not own a content-producing network have reason to protect the value of video because they receive revenue from it. Nearly all major Internet service providers also run a cable subscription service. Why allow customers to obtain video online when you can restrict or cap bandwidth and force them to pay a cable subscription fee? Consumer protection enforced by national governments is the only barrier to this reality, and all the major service providers are lobbying hard to erode it.

It’s A Grim Future

Let’s face it – the digital revolution of video is coming up short of the one that changed the music industry. Major networks are seeing fewer viewers of some major shows, but the people who were watching the shows on major networks are not always turning to online alternatives. Instead they’re often running to niche channels (which are usually owned by the same networks) or digital content (which is once again owned by the same networks or provided via contracts with the same).

The networks producing content, in collusion with service providers, could simply squeeze online alternatives out of existence. The slow progress of bandwidth caps, the takedown of file sharing networks (like The Pirate Bay, which is now legally banned in the United Kingdom) and the profit squeeze placed on alternatives like Netflix makes it seem unlikely that video will one day become as affordable as music.

Even if we somehow dodge current service providers, our increasingly wireless world throws us into the maw of mobile carriers, which have already set a precedent of low bandwidth caps, selective access to content and high service charges.

What could change this course? A reduction in copyright duration, an outright ban of all bandwidth restrictions and the funding of publicly supported high-bandwidth networks by nations the globe over would be a good start. We also need either a smaller high-quality video format or a massive increase in bandwidth. Seems like a tall order – but I can dream, right?

Image Credit: Guillaume Paumier, Rose Fire Rising