Random Access Memory, more frequently known as RAM, is a common component that every PC needs. Users building a new computer always need to buy it, and those with older hardware often seek to upgrade it as an easy way to improve performance. RAM can also be found in a variety of products like smartphones, tablets, video cards and more, though in those cases, it is usually soldered to a mainboard and can't be replaced.

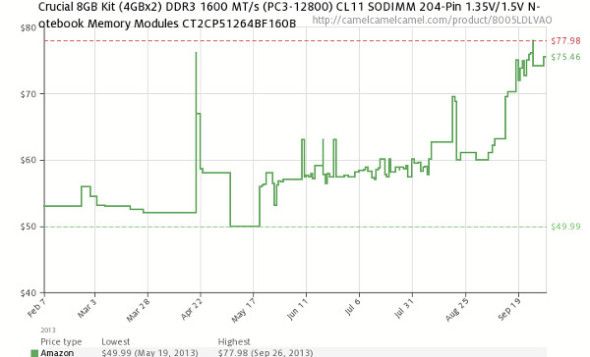

The sheer amount of this technology in the market would lead most people to assume it is a cheap product with relatively stable prices. That's how mass-produced commodities usually work, after all; no one worries about the price of bubble gum going up next year. Yet consumer RAM prices have, since the beginning of this year, nearly doubled. But why?

RAM Is Expensive To Make

http://youtu.be/3s7KG6QwUeQ

RAM, like most things, is made in a factory, but not just any factory will do. Extremely complex equipment is required to fabricate the chips and, because impurities in or on the silicon can cause defects, the environment must be extremely clean. There's also the matter of programming the machines, a task which in itself require significant engineering expertise.

And there's more to it than just the RAM itself. The memory must be attached to either a PCB (printed circuit board) stick or the mainboard of the product it will ship in. That PCB must also be produced in a clean environment by an extremely precise machine that again takes training to properly operate, as just one improper solder could result in thousands of defect chips. And finally, once assembled, the finished product must be tested for quality and then placed into the finished product.

What you have, then, is a recipe for extremely high start-up costs. The production equipment runs anywhere from several hundred thousand to several million per machine, and a factory may include tens or hundreds of them. These then must be placed in a secure, clean environment, which means only the best industrial real estate will do. And finally, a team of engineers must be hired to oversee production, and their valuable knowledge doesn't come cheap.

If you've ever wondered why many of the world's hardware design companies (such as AMD, ARM and NVIDIA) don't produce their own chips, well, this is why. The extreme cost of starting production means there's no such thing as an indie RAM production shop, and unlike other industries, the operating production line may only last three to five years. A change in standard or a new production technology often forces manufacturers to re-tool their equipment or buy entirely new machines.

Disaster Happens

The market for mechanical hard drives saw prices turn upwards last year following severe flooding in Thailand that impacted many factories involved with production. Prices didn't start to recover substantially until this summer and, for some products, are still higher than they were before the floods hit.

This event underlined a weakness in the consumer electronics industry; many products come from only a few providers in a limited geographic area. All of this connects back to the high start-up and operating costs I already mentioned. Because the business can be tough, and it relies on skilled engineers, most manufacturers operate in just a few areas that provide an educated workforce and favorable economics. That means Thailand, Taiwan and China. Any disruption, even if it impacts just a single company or factory, can cause prices to spike.

Such an event recently hit the RAM market when a factory owned by SK Hynix caught on fire, which caused the average price of a DDR3 chip to rise over 40% in just two weeks. The company doesn't generally make end-user products, but rather sells chips to others, so this did not result in an immediate 40% increase in the price of computer memory. But it certainly didn't help the market which, as mentioned, has seen prices double over the last year.

Demand And Supply Is Complex

The high cost of producing hardware does not just cause prices to rise when disaster strikes. Spikes can also occur because of the introduction of new technology or increased demand. Normally, such a rise would cause other companies to enter the market in search of a profit, but the high cost of producing RAM creates a barrier to entry few want to leap.

History provides some great examples, and perhaps the best was the transition from DDR2 to DDR3. Since DDR2 was older and inferior, common sense would say that its price would go down as DDR3 was introduced. Instead, the opposite occurred because switching production from DDR2 to DDR3 meant there were fewer DDR2 chips on the market. Prices surged and remain elevated to this day.

We're likely to see, and may in fact already be seeing, a similar trend with DDR3. The next standard, predictably called DDR4, will start to see adoption next year. That will cause production to shift towards the new standard, leaving fewer machines to make DDR3.

Increased demand from other markets is a factor, too, and not just smartphones and tablets are responsible. There's also been a steady rise in the need for RAM in server hardware, a phenomena most likely caused by cloud computing. All that hardware purchased by Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and others has memory in it, and manufacturers are shifting their attention away from consumers and towards this more profitable opportunity.

Conclusion

One trend defines the market for RAM, and that's the immense capital required to make it at all. There's no doubt that memory would be much less expensive if someone could set up a production shop down the street for a few million bucks, but that's not how the market works. Despite its proliferation, memory remains a very complex product that requires specific skills and machines to produce.

So long as that's true (and it will likely remain true for decades) the price of RAM will remain subject to significant changes that at times may occur within the space of just a few weeks. The best consumers can do is watch prices and buy when the market is at a low.

Image Credit: Tracy Olson/Flickr