The power of botnets is increasing. A sufficiently organized and globalized botnet will take down portions of the internet, not just single sites, such is the power they wield. Despite their huge power, the largest DDoS attack didn't use a traditional botnet structure.

Let's look at how a botnet's power expands and how the next enormous DDoS you hear about will be the bigger than the last.

How Do Botnets Grow?

The SearchSecurity botnet definition states that "a botnet is a collection of internet-connected devices, which may include PCs, servers, mobile devices and internet of things devices that are infected and controlled by a common type of malware. Users are often unaware of a botnet infecting their system."

Botnets are different from other malware types in that it is a collection of coordinated infected machines. Botnets use malware to extend the network to other systems, predominantly using spam emails with an infected attachment. They also have a few primary functions, such as sending spam, data harvesting, click fraud, and DDoS attacks.

The Rapidly Expanding Attack Power of Botnets

Until recently, botnets had a few common structures familiar to security researchers. But in late 2016, things changed. A series of enormous DDoS attacks made researchers sit up and take note.

- September 2016. The newly discovered Mirai botnet attacks security journalist Brian Krebs' website with 620Gbps, massively disrupting his website but ultimately failing due to Akamai DDoS protection.

- September 2016. The Mirai botnet attacks French web host OVH, strengthening to around 1Tbps.

- October 2016. An enormous attack took down most internet services on the U.S. Eastern seaboard. The attack was aimed at DNS provider, Dyn, with the company's services receiving an estimated 1.2Tbps in traffic, temporarily shutting down websites including Airbnb, Amazon, Fox News, GitHub, Netflix, PayPal, Twitter, Visa, and Xbox Live.

- November 2016. Mirai strikes ISPs and mobile service providers in Liberia, bringing down most communication channels throughout the country.

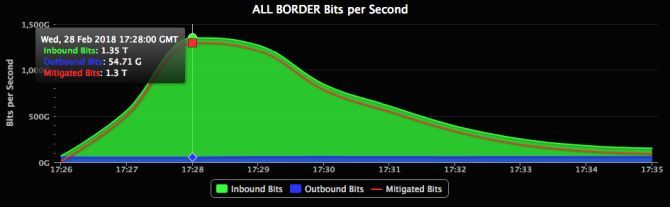

- March 2018. GitHub is hit with the largest recorded DDoS, registering some 1.35Tbps in sustained traffic.

- March 2018. Network security company Arbor Networks claims its ATLAS global traffic and DDoS monitoring system registers 1.7Tbps.

These attacks escalate in power over time. But prior to this, the largest ever DDoS was the 500Gbps attack on pro-democracy sites during the Hong Kong Occupy Central protests.

Part of the reason for this continual rise in power is an altogether different DDoS technique that doesn't require hundreds of thousands of malware-infected devices.

Memcached DDoS

The new DDoS technique exploits the memcached service. Of those six attacks, the GitHub and ATLAS attacks use memcached to amplify network traffic to new heights. What is memcached, though?

Well, memcached is a legitimate service running on many Linux systems. It caches data and eases the strain on data storage, like disks and databases, reducing the number of times a data source must be read. It is typically found in server environments, rather than your Linux desktop. Furthermore, systems running memcached shouldn't have a direct internet connection (you'll see why).

Memcached communicates using the User Data Protocol (UDP), allowing communication without authentication. In turn, this means basically anyone that can access an internet connected machine using the memcached service can communicate directly with it, as well as request data from it (that's why it shouldn't connect to the internet!).

The unfortunate downside to this functionality is that an attacker can spoof the internet address of a machine making a request. So, the attacker spoofs the address of the site or service to DDoS and sends a request to as many memcached servers as possible. The memcached servers combined response becomes the DDoS and overwhelms the site.

This unintended functionality is bad enough on its own. But memcached has another unique "ability." Memcached can massively amplify a small amount of network traffic into something stupendously large. Certain commands to the UDP protocol result in responses much larger than the original request.

The resulting amplification is known as the Bandwidth Amplification Factor, with attack amplification ranges between 10,000 to 52,000 times the original request. (Akami believe memcached attacks can "have an amplification factor over 500,000!)

What's the Difference?

You see, then, that the major difference between a regular botnet DDoS, and a memcached DDoS, lies in their infrastructure. Memcached DDoS attacks don't need an enormous network of compromised systems, relying instead on insecure Linux systems.

High-Value Targets

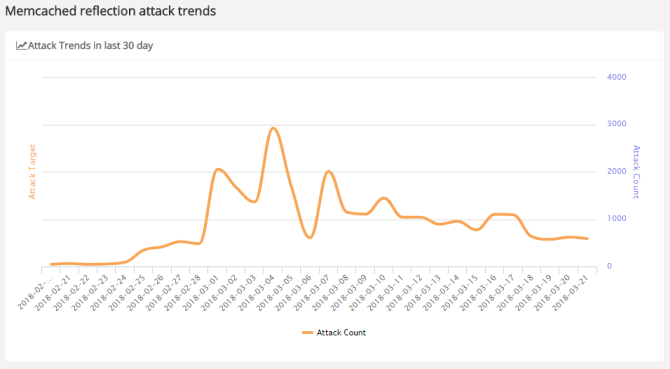

Now that the potential of extremely powerful memcached DDoS attacks is in the wild, expect to see more attacks of this nature. But the memcached attacks that have taken place already---not on the same scale as the GitHub attack---have thrown up something different to the norm.

Security firm Cybereason closely tracks the evolution of memcached attacks. During their analysis, they spotted the memcached attack in use as a ransom delivery tool. Attackers embed a tiny ransom note requesting payment in Monero (a cryptocurrency), then place that file onto a memcached server. When the DDoS starts, the attacker requests the ransom note file, causing the target to receive the note over and over again.

Staying Safe?

Actually, there is nothing you can do to stop a memcached attack. In fact, you won't know about it until it finishes. Or, at least until your favorite services and websites are unavailable. That is unless you have access to a Linux system or database running memcached. Then you should really go and check your network security.

For regular users, the focus really remains on regular botnets spread via malware. That means

- Update your system and keep it that way

- Update your antivirus

- Consider an antimalware tool such as Malwarebytes Premium (the premium version offers real-time protection)

- Enable the spam-filter in your email client; turn it up to catch the vast majority of spam

- Don't click on anything you're unsure about; this goes double for unsolicited emails with unknown links

Staying safe isn't a chore---it just requires a little vigilance.

Image Credit: BeeBright/Depositphotos