Considering where our data is going to leak from is a difficult task. We take the necessary precautions across our devices, installing antivirus software, running malware scans, and hopefully double- and triple-checking emails for anything suspicious. These are only a few of the potential attack vectors awaiting us.

Security researchers have revealed that aside from our "regular" devices, one of the newest forms of technology could be providing attackers with an unexpected but easily-accessible angle to steal our personal data. Fitness trackers have recently come under the security spotlight after a technical report highlighted a series of serious security flaws in their designs, theoretically allowing potential attackers to intercept your personal data.

Fatal Fitness Flaws

Fitness trackers have seen an unprecedented rise in popularity throughout the last few years. The 4th quarter of 2015 alone saw a massive 197% rise in year-on-year sales, from 7.1 million to 21 million units. Market analysts Parks Associates estimate the global fitness tracker market will continue to grow, rising from $2 billion in 2014 to $5.4 billion in 2019. These are significant gains, indicating the number of users potentially exposing themselves to this previously-unknown attack vector.

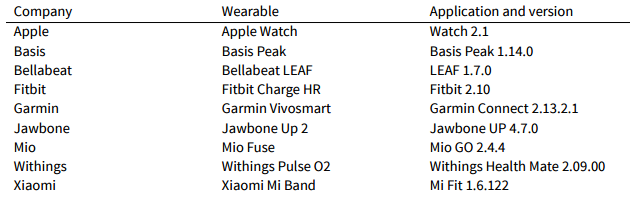

Canadian not-for-profit research organization Open Effect, and interdisciplinary research laboratory Citizen Lab, examined eight of the most popular fitness wearables currently available: the Apple Watch, the Basis Peak, the Fitbit Charge HR, the Garmin Vivosmart, the Jawbone UP 2, the Mio Fuse, the Withings Pulse O2, and the Xiaomi Mi Band.

The combined research report sought to discover the steps the technology companies are taking to protect and maintain your data security. While we know and understand fitness trackers will collect heartbeats, footsteps, calories, and sleep data, the researchers explored just what happens to that data when it is in the hands of the device developers.

What data is sent to a remote server? How do the technology companies secure the data? Who is it shared with? How do the companies actually make use of the information?

Key findings included:

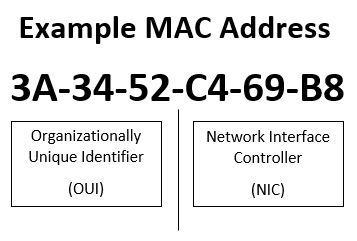

- Seven out of eight fitness tracking devices emit persistent unique identifiers (Bluetooth Media Access Control address) that can expose their wearers to long-term tracking of their location when the device is not paired, and connected to, a mobile device.

- Jawbone and Withings applications can be exploited to create fake fitness band records. Such fake records call into question the reliability of that fitness tracker data use in court cases and insurance programs.

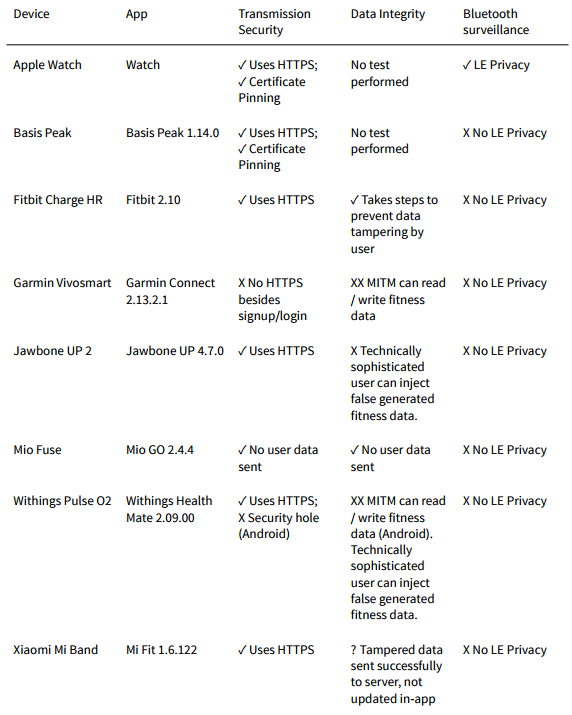

- The Garmin Connect applications (iPhone and Android) and Withings Health Mate (Android) application have security vulnerabilities that enable an unauthorized third-party to read, write, and delete user data.

- Garmin Connect does not employ basic data transmission security practices for its iOS or Android applications and consequently exposes fitness information to surveillance or tampering.

Persistent Unique Identifiers

Wearable technology emits a persistent Bluetooth signal. Whether smartwatch or fitness tracker, this signal is used to consistently communicate with your smartphone. Their communication with the external device is maintained using a MAC (Media Access Control) Address, uniquely identifying the fitness tracker.

In the context of fitness trackers, personal data security maintenance demands these addresses be randomized to ensure the user cannot be tracker and identified by the MAC Address. Bluetooth beacons, used with increasing frequency in shopping malls to create targeted mobile advertising, can track and profile those devices using a single MAC Address (they can also be built by anyone with a suitable, compact computer). Indeed, of the devices tested only the Apple Watch randomized its MAC Address "at an approximately 10 minute interval" to protect its user's identity.

With the persistent MAC Address logged, the user's location could feasibly be tracked from beacon to beacon. If a shopping centre decides to collect user location information throughout their shopping visit, the data could be sold to a marketing agency, or other data broker, without first notifying the user. If a single data broker can purchase multiple profiles, information can be collated to build sophisticated targeted advertising profiles, activated each time the user (and their unique device identifier) enters the building.

The Apps Are Just As Bad

Each fitness tracker comes with its own monitoring app, capturing the plethora of fitness-related data and translating it into a nice visual depiction of the users actions. However, the apps themselves have been found to leak personal information, at multiple transmission locations.

For instance, one would expect any transmission of personal data to be encrypted using HTTPS at the very least; the Garmin Connect failed to do even that, leaving user data passively exposed to a potential eavesdropper.

Similarly, although the Bellabeat Leaf and Withings Health Mate communicate with remote servers using HTTPS, both companies sent plaintext emails to users to confirm their sign-up credentials, leaving users open to man-in-the-middle attacks. Any attacker with a working knowledge of the Bellabeat or Withings API could access a wide range of personal fitness information in minutes. This form of attack could also be used to push malicious or false data to the wearable or the user's phone, too.

Data Tampering

Three of the fitness tracker apps observed "were vulnerable to a motivated user creating false generated fitness data for their own account," tricking company servers into accepting fake data. Open Effect and Citizen Lab created several applications designed to trick the fitness tracker servers into accepting false information, with Bellabeat LEAF, Jawbone UP, and Withings Health Mate coming up short.

"We sent a request to Jawbone stating that our test user took ten billion steps in a single day"

Their application evenly distributed step timings into fixed intervals over a desired timeframe, creating an artificial distribution of steps. The researchers concluded a more sophisticated approach would "randomly allocate steps to establish a more realistic-looking distribution" to further escape detection.

Why Is This A Problem?

Fitness trackers can maintain a continual stream of personal data collection. Common data collection vectors include footsteps, heartbeat, sleep patterns, elevation, geolocations, quality of activities, and types of activities.

Some of the fitness trackers encourage their users to engage in additional fitness or social activities, such as specifying food for calorific counting and analysis, personal mood at specific times of the day (also in relation to activities and food consumption), to log their fitness goals and track progress over time, or to compete against other fitness enthusiasts in gamified social media-styled dashboard environments.

The issues raised by Open Effect and Citizen Lab illustrate the dangers in relying on fitness trackers to provide reliable personal data in a range of situations. Fitness tracker data has been used to secure insurance policies, or represent progress made with medical problems, yet we see the data could easily be falsified.

Furthermore, do these data issues make the very nature of these fitness tracker technology companies questionable? How do these poor attempts at data protection translate to their other products? The problem is not bound to fitness trackers alone, and more should be done by both citizens and regulators to ensure user data is protected at all times, lest we find entire industries undermined by their seeming lack of care and discretion with private data.

What Next?

The report findings are clear: increased security based upon the recommendations of Open Effect and Citizen Lab. Personal and private security is serious, and we should address issues as they arrive. But it isn't only enhanced security that is needed. Fitness tracker users need to understand where their data is sent to, where it is stored, and which other parties have access to it.

The onus is on the technology companies to communicate with their users the full depth of technical surveillance they have acquiesced too, whether they realize it or not, along with its potential risks.

Is it time to throw your fitness tracker away? Probably not, especially if you have an Apple Watch. Despite mixed reactions toward the findings of the technical report from the fitness tracker manufacturers, it is unlikely that these vulnerabilities will exist for long.

Or, we can at least hope they will not exist for long.

Are you worried about your fitness tracker? Have you lost data through wearable technology? What happened? Let us know below!