The future of your browsing habits could change.

Ad-blocking is controversial: there are no two ways about it. Readers hate ads, publishers need to make money. That's just how it is. But until recently, it's been a relatively one-sided battle in which readers had all the tools they needed for ad-blocking, and publishers just had to ask to be whitelisted. But things are changing.

Companies are starting to fight back against ad-blocking, and it could affect your browsing experience, whether you use an ad blocker or not.

Here are four interesting ways in which publishers are looking to get proactive about recouping ad revenue.

Legal Challenges

In some countries, taking legal action has been a preferred method for publishers. Eyeo, the developers of Adblock Plus (ABP) is in their cross-hairs. In the past couple years, Eyeo has won some legal cases in Germany, and we've heard rumblings of potential suits in both France and the United States. But, with the repeated victories in Germany, companies are reconsidering their tactics.

Most suits seem to stand on the idea that ad-blocking is an anticompetitive practice. Governments want to stifle this before it becomes a Frankenstein. Monopoly reduces competition in the marketplace and it can have disastrous economic results. Price fixing, exclusive dealing, territory division, and certain types of digital rights management are all examples of anti-competitive practices.

A spokesperson for ProSieben, a German publisher that lost against Eyeo, even went so far as to say that its loss in court was an attack on freedom of the press. Copyright laws have also been discussed, as some publishers claim that ad-blockers alter their pages without their consent (though this claim seems unlikely to hold much water, as publishers often don't know which ads are being served by third-party networks on their own pages).

It's a safe bet that legal challenges to ad-blocking will continue, and that they'll be mired in appeals courts for years to come. Maybe, until a judge sides with the publishers, at which time ad-blocking companies will start their own appeals process, which will end . . . probably sometime around never.

Watching these legal processes unfold in different countries will also be interesting, as the Internet is a strong globalizing force, and any legal action taken against ad-block developers or users will be quite difficult to enforce.

The Rise of Paywalls

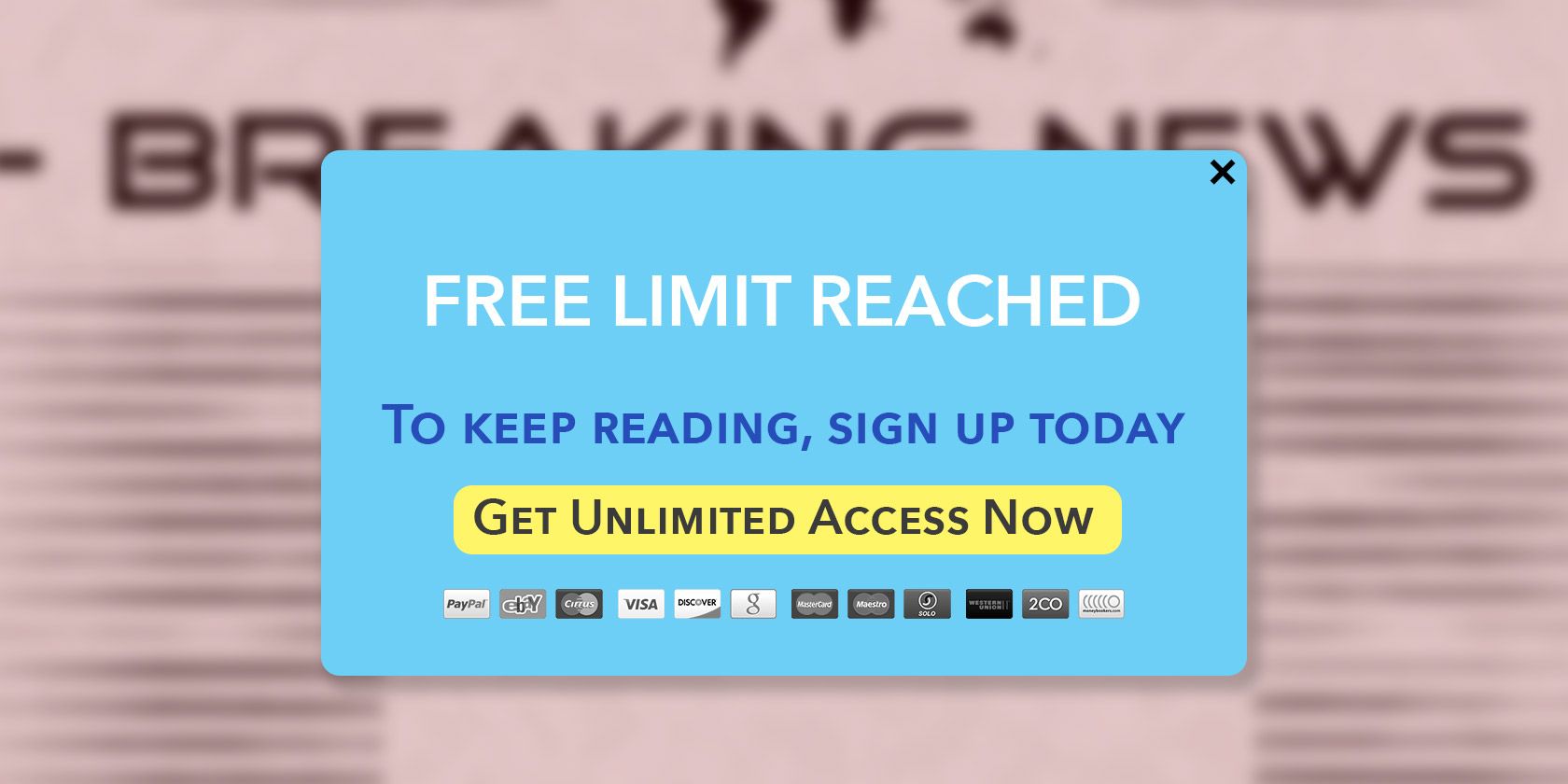

The most tragic consequence of the proliferation of ad-blocking is the rise in use of paywalls that deny readers access to high-quality content. Of course, paywalls have been used by the websites of traditional media outlets for years in an effort to stop giving away their articles for free, but ad-blocking seems to have accelerated the discussion of additional paywalls, if not its adoption.

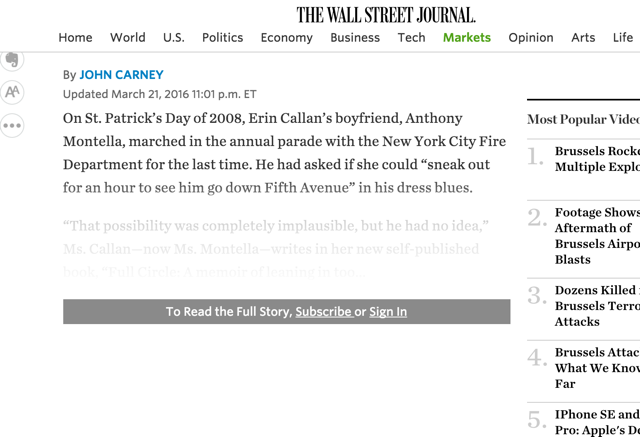

The number of sites that have paywalls is difficult or impossible to measure, but if you spend a lot of time online, you've probably noticed an increase over the past few years. Big names like the New York Times, the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal, the New Yorker, and the Harvard Business Review are some of the biggest names to have experimented with paywalls.

Whether paywalls are effective in making money for newspaper sites is up for debate, with some people saying that they actually cause an increase in revenue, while others saying they just drive away potential readers. It's easy to see why a publisher might be interested in this method when faced with the prospect of losing ad revenue, but whether it works is another story.

While content blocking (see next section) is likely to increase rapidly, the future of paywalls seems indeterminate at this point. Some sites have seen success with them, and will likely continue to use them. Others, have had less success and probably won't (especially as users get better at sneaking by paywalls). We'll just have to see what happens.

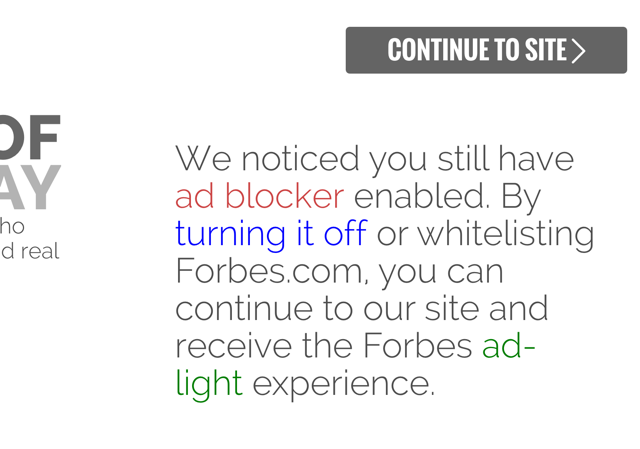

Enforce with Content Blocking

The newest and arguably most irritating way for publishers to make money on their sites is content blocking, or an "ad-block wall": not allowing users to see any portion of the website while they have an ad blocker enabled. Instead, you'll see a pop-over or a screen telling you that you won't be able to see anything on the page without whitelisting the site or turning your ad-blocker off. This is becoming a popular strategy.

GQ and Forbes are currently using this tactic, and other sites have trialed it. WIRED is planning on instituting an ad-block wall soon. Interestingly, Forbes offers you a trade: turn off your ad-blocker and you'll get the "ad-light" experience, which they call "less intrusive." What they don't tell you right up front is that the ad-light version of the sites only lasts for 30 days, after which you presumably get the full-force ads or need to pay up.

This type of action is getting more popular, and that trend seems set to continue. At least some publishers are reporting success with this method. According to Fortune,

Matthias Dopfner, CEO of German media giant Axel Springer[,] told the Financial Times that after implementing a similar block at its newspaper Bild, more than two-thirds of users chose to turn off their ad-blocking software. That meant 3 million more visits that could be monetized through advertising, he said.

That's a lot of money, and Bild's success is likely to galvanize other publishers into at least trying to deny ad-blocking users access to their site. Though it remains to be seen if other sites can leverage this technique to the same degree of success.

Business Insider reported that many sites haven't seen good results or have technical difficulties that make the ad-blocks walls easy to get around, making the overall effectiveness of this method questionable. As companies continue to innovate in this area, the situation will change, but exactly how is anyone's guess.

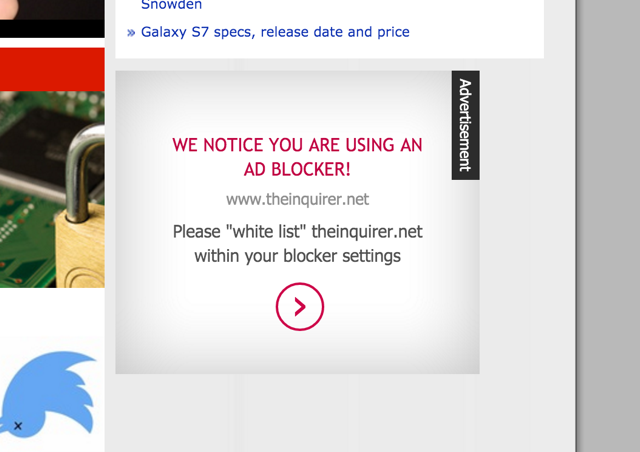

The Polite Plea

You've almost certainly seen this strategy used, and recently; websites recognize that you're using an ad-blocker, but instead of denying you access, they simply replace ads with a (usually) polite request that you consider donating to the site to keep it running.

I wasn't able to find any statistics on whether this tactic works, but I have to imagine that it's not effective. A publisher's decision to run with this tactic instead of an entire ad-block wall is easy to understand, but if it continues to be ineffective, it's likely that we'll see more sites switching to more aggressive measures to monetize their page views.

How Does It Matter to You

With continuing litigation and the proliferation of aggressive anti-ad-block measures like paywalls and content blocking, the future of your browsing experience is in the balance of the ad-block debate, whether you're blocking ads or not. And no matter how you feel about it, it is a debate. There are strong arguments on both sides, and a lot of negotiating power in the hands of proponents of both views.

It's impossible to predict what the next salvo fired by either side will be, but I'm confident in saying that it could directly affect how we spend time on the Internet and what we're able to see for free. This is true whether you use ad-blockers or not.

What do you think about the measures that publishers are taking to reduce or drop ad-blocking on their sites? Do you donate to sites that ask politely? Or do you just block all ads everywhere? What happens when you hit an ad-block wall? Share your thoughts and experiences below!