"How many people here know what the resolution is on the new Macbook Pro?"

Clay Johnson asked that question earlier this year while speaking to a class in Washington, DC. Eighty percent of the class knew the answer (it's 2880×1800).

Johnson asked another question. "What is the child poverty rate here in DC?"

Not one student knew the answer (29.1 percent).

"What's more relevant if you have $2000 to spend?" he asks me. "Your laptop works fine. I don't want to lay a guilt trip on you, but somebody should know, out of a class of fifty people – one person should know that the child poverty rate is 29 percent."

I'm talking with Johnson over Skype; he's in DC, I'm in Boulder, Colorado. I have to admit: I don't know the child poverty rate in Boulder (17.5 percent).

The point, Johnson explains, is knowing the poverty rate in your city can help you be a better citizen and possibly help you build a better community. Knowing the resolution of a just-released laptop cannot.

But the average person is more likely to read about the new MacBook's resolution than the poverty rate where they live.

"Is it that newsworthy that a laptop was released?" he asks me. "Because that's apparently that's what's newsworthy today".

‘Going Straight To Dessert, Every Time’

Johnson is the author of The Information Diet, a book with a unique core metaphor: heavily processed information, like heavily processed food, isn't healthy but for some reason we can't get enough of it.

Email. Social networks. Blogs. Online video. People today consume more information than ever before, and typically only consume the things they really, really like. Johnson compares this to a bad diet.

"If you only ate what you want then we'd probably put the dessert section at the top of the menu, rather than at the bottom," he says. "I think the same thing is happening with journalism: we're going straight to dessert every time."

Technology journalism today is written by people who don't understand technology, and it basically amounts to advertisements for Apple, Google, Amazon or Microsoft.

Tech-savvy people are no exception.

"Technologists aren't picking up a newspaper: they're going to Hacker News or Reddit or Tech Meme and reading stuff that really doesn't matter to them," he says. "Technology journalism today is written by people who don't understand technology, and it basically amounts to advertisements for Apple, Google, Amazon or Microsoft."

As a technology journalist I can't help but reflect on that. I linked to a MacBook Pro article above, but could hardly find a MakeUseOf article about child poverty.

72 Trillion Dollars

They need to create cheap, popular information.

Later I bring up a particular incident: various websites reporting the RIAA demanded $73 trillion dollars from Limewire.

"Isn't that more money than exists on earth?" he laughs.

"Yeah," I say, "But news organizations reported it as fact. Why do you think that is?"

"It probably got people to click," Johnson says. "That's how our media has defined itself now. Our food companies industrialized and created incentives, so there is now a responsibility to create cheap, popular calories. Now we've industrialized media, and they need to create cheap, popular information."

Fact checking isn't cheap, and statistics aren't popular. So we get stories about celebrities, sideboob and new laptops. We only eat dessert.

Social networking isn’t helping: people tend to share dessert with their friends online more than vegetables.

Don't Mindlessly Consume: Schedule

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNFNOSzik14

It's not just journalism Johnson's concerned with, though: it's the amount of time we spend consuming irrelevant information overall.

"Time is our only non-renewable resource," he tells me. "You can always get more money, you can always get more food...but you can never get back lost time."

Email and social networking can be valuable; constantly checking for updates instead of accomplishing things isn’t. That’s time we can get back if we're conscious about it, says Johnson.

"Make it work around your lifestyle rather than getting lost in it all day," he says. "I think it's just a vital part of a healthy lifestyle to say 'I'm going to schedule what time I'm going to spend on email, schedule what time I'm going to spend on Twitter, schedule what time I'm going to spend on Facebook or Google Plus.'"

Sound impossible? Information doesn't need to be overwhelming, he explains: it becomes overwhelming because we constantly pay attention to it.

I check email from 8 to 9 and 2 to 3. That's when I do my email. And guess what? My email gets done.

"This idea that we're getting deluged is in part because we get addicted to waiting for email, get addicted to seeing what's happening on social networks," he tells me. "I check email from 8 to 9 and 2 to 3. That's when I do my email. And guess what? My email gets done. Since I started the information diet there's never been more than 50 messages in my inbox."

Johnson regularly appears in the media, runs a fairly popular blog and gives regular talks across the USA – you probably don't get more email than him.

And if you're afraid you'll miss something if you don't constantly check your email and social networks, Johnson disagrees.

"You are not going to sit on your deathbed and be like 'Man, if only I was notified of that Living Social coupon in 2012, and got that laser hair removal: then I could have lived a happy and fulfilled life.'" he says. "That's just not going to happen."

A Surprisingly Apt Metaphor

There's one core idea in Johnson's book: we should think about information the way we think about food.

"How did you come up with this metaphor?" I ask.

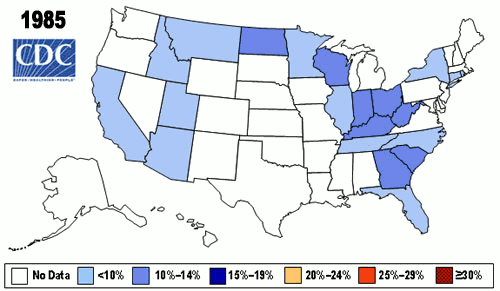

"The first thing that sparked my attention was a document from the CDC," he responds. "It shows obesity over time, state by state."

"I started looking at that and I started thinking about the polarization of politics," he says. "I fantasized about what this obesity map would look like as an electoral map. That's when I started noodling around with the idea."

It's impossible to discuss Johnson's ideas without wading into politics in general and healthcare in the USA specifically, but the overall themes apply everywhere.

"My mom got cancer, and our health insurance went up by a factor of ten," he tells me. "My dad had to go work for the state of Georgia in order to keep her insured. My dad was 70 at the time, and had retired. We didn't have a sports car or a house that was too big. We were a middle class family."

Johnson didn't understand what anyone was supposed to do under those circumstances.

Getting Into Politics

"It drove me into politics," he said. "I got into healthcare, trying to solve that problem, so I went to work for Howard Dean in 2004. I thought if I helped elect a president that would solve it."

Dean, you'll recall, lost the primary to John Kerry, who lost the general election to incumbent George W. Bush.

Johnson continues: "Then I thought it wasn't just a president I needed to elect: it was a whole bunch of Democrats. So I started this company called Blue State Digital, and it turns out we did help elect a bunch of Democrats, including eventually a President."

But it still wasn't enough, according to Johnson. Healthcare remained broken – apparently electing Democrats wasn't the solution.

Transparency Isn't The Solution Either

"So then I thought the problem was maybe the lobbyists," he says. "So I went to work with the Sunlight Foundation and tried to solve things that way. I thought if we put a bunch of data out there people would make a rational decision, see what's going on with their health insurance and demand change."

It’s a common idea among technology enthusiasts: giving people access to raw information will keep them informed. Johnson believed it until a single sign changed his mind.

"Keep your government hands off my Medicare" it said. The problem, of course, being that Medicare itself is a government program.

I realized we have a community of people that are highly informed but not well informed

"That hit home for me," says Johnson. "I realized we have a community of people that are highly informed but not well informed. I'm not defining people as being well informed for agreeing with me – I don't think that that's the case. I think it's more about knowing the fundamental structures of how things work and, obviously, knowing that Medicare is a government-run program is a requirement for engaging in the health care debate in this country."

It changed the way Johnson thought about information.

"I felt like this transparency thing, while important, wasn't enough," he says. "You have to convince people to look for this stuff and seek it out, because it's not being given to them by the mainstream media or by any media."

Confirming Our Own Worldviews

There's a difference between what it is that you want and what it is that you need.

It’s frustrating for technologists to admit, but the Internet isn't solving the problem. Johnson explains most people are usually reading things they already agree with.

"When you read an article online you scroll down to the bottom and you see a thing that says 'other articles like this one'", Johnson says. "So you get stuck in a place where you're just always reading more and more of the stuff that you want to hear."

Alternative media doesn't necessarily help.

"If people seek out alternative media they're generally seeking out alternative media that agrees with them," he says. "If you play that out a little bit we end up with this real big problem, which is America existing in two different realities reading from two different news sources: a red one and a blue one.

"Our ability to deliberate and synthesize the best of ideas goes away."

It's a political problem, sure, but it goes beyond that.

"You see this with Apple fans, and Google fans," says Johnson. "The Apple pundits out there seem to use the same sort of weird tactics that the political people here in Washington DC do. It's very strange."

The cause, as always, is clicks. People click what they want.

Johnson continues: "There's a difference between what it is that you want and what it is that you need."

SOPA: Long-term Internet Activism

Nobody is going to put The Internet at the top of their voting issues.

Johnson sees his early political work with the Dean campaign as a consequence of consuming bad information.

"We became delusional on the Dean campaign because we kept saying 'we're gonna win,' and 'we're the best,'" he recalls. "And it turns out we weren't the best, at least in the voter's eyes."

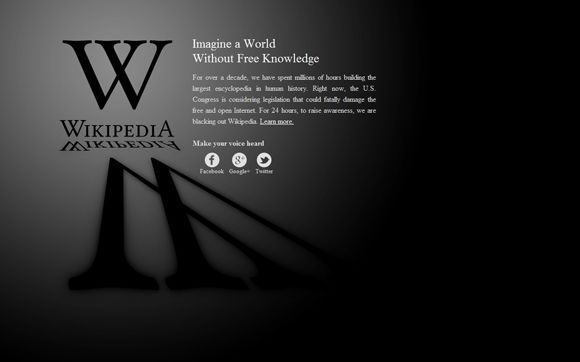

The anti-SOPA protests earlier this year in the USA put off Internet-regulating legislation by causing phones on Capitol Hill to ring off the hook, but that won't work forever according to Johnson. Blackouts on sites like Reddit and Wikipedia won’t work forever without persuasive information.

"Eventually Congress is going to say 'we're not going to listen to The Internet anymore'", he says. "And they're going to get re-elected anyway, because nobody is going to put The Internet at the top of their voting issues. People care about healthcare, or war, or guns. No one is going to make compromise on any of those things for intellectual property on the Internet legislation.

"So you need to find out how to distil this stuff from popular movements into dispassionate and calculating action."

It's hard work, but it’s necessary.

Consequences to Consumption

Clicks are votes. If you're checking out the side boob section of the Huffington Post there's going to be more sideboob stories.

"I feel like the Huffington Post, Drudge Report and The Daily Caller are sites that are catering towards the base of society," Johnson tells me. It's easy, after hearing that, to simply blame the sites for putting up simplified content, but that's not entirely fair: the sites deliver content they think will be popular.

"Our media consumption choices have consequences," says Johnson. "Clicks are votes. If you're checking out the side boob section of the Huffington Post there's going to be more sideboob stories."

Reading garbage content doesn't just affect you: it affects everyone else who looks at a particular site.

"Your friends don't know [what you're reading], but somebody does. The editors are saying 'oh, this 30 year old white male likes Kardashians, we should give them more Kardashians and less investigative reporting.'"

The result: every time you ignore an investigative piece to read some celebrity gossip, or ignore a policy article to read instead about the political horse race, you're telling websites what sells. It's a potentially never-ending cycle, one at least one news organization has formalized.

"AOL put it out in writing in The AOL way, which was leaked," Johnson tells me. "An average piece of AOL content has to cost on average $80, and they need to get 50% gross margin on that.

"There's no way to do that other than to sensationalize the headline and do very little original research."

On Advertising

"Is part of the problem people aren't willing to pay for quality content?" I ask.

"We do pay for content," he quickly responds. "I think we just have to wake up and understand that we're paying for it. Advertising is not a cost free payment mechanism – it's just an opaque one. When a pizza company advertises and talks you out of cooking dinner tonight and ordering pizza instead, you've effectively paid for your content. You got a television show for $20 and it came with a free pizza."

I ask if the information would be better were we willing to pay for it up front.

"You see that now," he responds. "A lot of the best content sources are reader supported or viewer supported. NPR, which does a fantastic job at reporting, is almost entirely listener supported." HBO and iTunes are other good examples, he says.

Avoiding ads can help you cut back on information overload but it can also save you money.

"I encourage a lot of people who are on information diets to sit down and do the math. Say [a cable subscription] is $100 a month, which is $1200 a year, would you spend less than $1200 a year in the iTunes store?

"Then you just have to figure out whether it's that important for you to watch those shows as soon as they come out or whether you can wait a season."

Tweaks You Can Make

There is never anything you're going to miss out on on Facebook. It's just never going to happen.

Johnson thinks people should schedule their media consumption instead of mindlessly consuming throughout the day. MakeUseOf being a technology site, I asked Johnson what tweaks people can make to their technology to avoid bad information habits.

Enemy number one, he told me, were notifications.

"Eliminate anything that's push or notifications," he said. "I think notifications are evil."

Why single out notifications? Because they pull our attention from what we're trying to do and pull us instead into our email and social networks – discouraging us from interacting with them only during scheduled times.

"There is never anything you're going to miss out on on Facebook," he says. "It's just never going to happen. Nothing requires your immediate attention on Facebook."

The advice continued.

"Stop using your iPhone as an alarm clock," he said. "When you do that, you've awakened and you now have your iPhone in your hand...what are you going to do? You're going to check your email after you've turned off your alarm, and that stuff can wait."

In his book Johnson suggests instead doing something productive first thing in the morning.

Oh, and while you're at it, turn off notifications on your phone.

"If you have push email on there activated, turn it off," he says. "Turn off notifications for every single app that you've got. There is never, ever, a reason you need to know now."

Johnson also recommends finding a tool to track what you're doing with your time on the computer; he provides a list of resources at resources.informationdiet.com, including these programs:

- RescueTime keeps track of what you’re doing on the computer, helping keep you responsible by showing you accurately how much time you’re wasting instead of working.

- AwayFind lets you know when people you find important email you. The idea is you’ll spend less time looking at your inbox, but be aware: this could be distracting if not used properly.

- Sanebox only shows you important emails, helping you ignore the fluff until you have time.

Johnson’s site also includes links to places you can turn off email notifications for all of your social networks.

The site makes it clear that installing tools isn’t enough: “Just like cleaning the junk-food out of your kitchen won’t make you lose weight if you simply choose to eat out all the time, an information diet is less about installing tools and more about making conscious decisions about the information you consume.”

More information

Sticking to an information diet, ultimately, is about discipline. I ask what people can do to find the stength to follow-through.

"You can read my book," he responds, laughing, before pointing out there is a lot of helpful literature out there: Howard Rheingold's NetSmart and David Weinberger's Too Big to Know, for example.

"What gets me excited about all this stuff is it's really clear, now, that there's consensus that there is some kind of problem," he says. "We're getting to a point where we're waking up to knowing that there's a problem. That's exciting to me."

Will we, as a society, act on that knowledge? It’s up to us.

Image Credits:

Cake picture by Helen Bird via Shutterstock http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=24512938

Photo of Clay Johnson by Joi Ito