Rarely will three letters invite as much opinion in the gaming community as DLC. Downloadable Content (DLC) is, in theory, meant to expand the confines of an existing game. That's more quests, characters, maps, items, and so on, directly from the developer to your game. In an already largely digitized gaming market, what can be better than buying a game and playing it through only to find out there's more game to play?

At least, that's the theory. The practice of DLC, however, is complex. Whether you love them or hate them, the games you play regularly -- even within the indie gaming market -- probably posses some type of micro-transactions or paid DLC addition. Surprisingly, that's true for both free-to-play games as well as $60, AAA franchise releases. This is something of a surprise, since free-to-play games often rely on in-game transactions and currency in order to pay development costs.

More than a sometimes nuisance, sometimes success however, DLC has become a part of gaming culture. That is to say, the practice of charging for downloadable content -- which at one point was a highly contested action -- is commonplace. Where this practice came from, how it manifests itself within the gaming community, and where it may lead are the questions this article will address. Read on!

The Early Years

There is no direct paternal line to the creation of modern DLC. That's because video games have always occupied a strange space between art and science, wherein there is no one definite way to make and update a game. So we'll start with a simple definition of what downloadable content actually is, and trace the practice backward. DLC is an official download -- released by the proprietary developer studio -- which provides additional content to a base game under the same title.

Modern DLC is often provided through a drip-drip fashion. Instead of remaking the game, or re-hauling large portions of the play area as with game expansions, DLC will provide users with different character or map installments intermittently. One of the first notable DLC features came through the real-time strategy (RTS) game Total Annihilation, created by Cavedog Entertainment, which would release new units every month on personal computers back in 1997.

Some of the most notable early expansion packs -- which you can consider large-scale DLC overhauls -- include Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, released around 1996, and the expansion Warcraft II: Beyond the Dark Portal released shortly thereafter. These early expansions typically continued the previous version's plot while providing users with new units, characters, or items much in the same way they do today. Blizzard went to continue this practice multiple times with their Warcraft, World of Warcraft, and Diablo franchises. Many games followed examples like Blizzard's thereafter.

Casual Gaming, the Quiet Giant

The precursors for modern console and desktop gaming DLC are, oddly enough, not the expansion packs of yesteryear. They're mobile and browser gaming -- often considered casual gaming. While most gamers don't consider mobile or browser gaming genuine aspects of the core community, there's no doubt that the practices of the mobile and browser gaming market have entered the folds.

How? Casual games often don't provide much in terms of writing, graphics, and overall productions. That's why many casual games around 2009-2010 relied on constant updates and attention-drawing game design in order to become popular.

Remember FarmVille? While you may not have played it, there's no doubt you received a notification about it at some point in time. In 2009 and 2010, FarmVille dominated the social media gaming scene. So much so, in fact, that it won the Game Developers Choice award for Best New Social/Online game. Not only that, the landmark moment that was FarmVille sparked a serious question within gaming media: why is it so outstandingly popular? If it seems like I'm over-inflating its popularity, consider the game's peak user base in early 2010:

"Twenty-six million people play FarmVille every day. More people play FarmVille than World of Warcraft, and FarmVille users outnumber those who own a Nintendo Wii."

Several theories concerning its popularity sprang up in order to understand this new phenomenon. All of these theories, whether they be psychological or financial, reflect modern gaming development. Consider Business Insider's 2010 analysis on FarmVille's popularity:

"FarmVille allows users to spend their in-game profits on decorations, animals, buildings, and even bigger plots of land. So users are rewarded for their work. Of course, people can sidestep the harvesting process entirely by spending real money to purchase in-game items. This is the major source of revenue for Zynga, the company that produces FarmVille.

Zynga is currently on pace to make over three hundred million dollars in revenue this year, largely off of in-game micro-transactions. Clearly, even people who play FarmVille want to avoid playing FarmVille. If people don’t play FarmVille because of the play itself, perhaps they play because of the rewards . . . . Zynga is constantly adding new items and giveaways to Farmville, often at the suggestion of their users. Hardly a week goes by that a new color of cat isn’t available for purchase. What fun."

Money-Grabbers

FarmVille was not a fun game by its very mechanics. It wasn't nearly as polished as console games. None of that mattered. FarmVille advertised constantly, within the growing social platform that birthed it. Facebook even reported that, at the height of FarmVille's popularity, the game accounted for a staggering 12% of its total revenue in 2011. It provided regular updates, required constant participation, and grew through a constant social insistence. Mental Floss speculated on why the game was so popular:

"The game was simultaneously boring and addictive. 'Gameplay' consisted of laborious, mechanical management tasks, and demanded that the player constantly return to the game at specific times to harvest crops in order to get virtual currency, so you could… plant more crops and set your clock again.

It's an amazing system: these game designers have devised a way to addict the player, then monetize that addiction by encouraging the player to bring in friends and (hopefully) pay real money to get ahead."

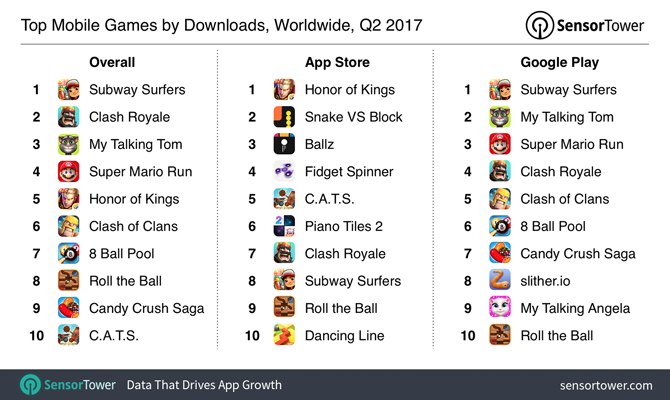

To a certain extent, calling a game casual is like calling a small house cozy. Casual games, which largely dominate both mobile and social media platforms, often tie in as much addictive game design as possible, requiring even more consistency than a regular console game. What's worse, the current top mobile game rankings all follow the path FarmVille laid out back in 2010 to some capacity.

When gamers complain about DLC, they aren't so much admonishing the concept. They are annoyed by the cash grab -- the obvious plot to squeeze money from a game. Do these techniques, first laid out with casual games, ooze their way into the large-scale development market?

Quick tidbit: overall, Candy Crush Saga is the 9th top mobile game. ThinkGaming ranked Candy Crush Saga the top grossing game available. The development company behind Candy Crush Saga, King Digital Entertainment, was bought by Activision Blizzard in 2016. This is to say: there may be less of a distinction between casual gaming and competitive gaming or console releases than most gamers realize.

The Circle of Profit

The advent of paid DLC isn't new. It's also surprisingly choice-based: if you don't want a DLC, you often don't have to buy it. Pay to play -- the strategy wherein developers will grant players tremendous power in exchange for monetized items -- is largely frowned upon, no matter the release. The issue, however, isn't solely DLC. There is a definite circle of profit that exists in gaming culture which, in its individual elements, seem to benefit the user. As a whole, however, it's difficult to avoid the obvious financial thrust behind them.

The circle goes: pre-order, release, in-game currency, micro-transactions, paid DLC, and season pass. While the quality of this content often depends on the developer, most games nevertheless occupy a few slots in the rotation and at times one is indistinguishable from another.

Subscription-Based Gaming

Not all games run through the complete motion of the profit circle. Nevertheless, most take part in at least a few. More than possibly overcharging consumers for frivolous content, these advents have created uncharted waters in the form of widespread subscription-based gaming.

Previously a practice used in MMORPGs like World of Warcraft and Eve Online, it seems few modern AAA titles are standalone. This isn't a surprise, as blockbuster franchise releases inevitably have a profit motive in min. But it's interesting to note that any given popular game has a secondary, paid counterpart in the form of paid DLC, micro-transactions, in-game currency, and so on.

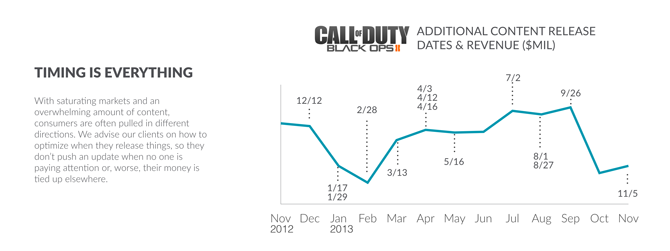

Have you bought a weapon skin lately? How about a loot crate? If not, you've probably at least seen an offer for something along these lines. It seems few games from notable developers don't continually offer new content, making the purchase of games seem like a down payment for the developers' future creativity. More than small purchases, however, DLC drive competition within the gaming market. The more often developers release DLC, the more often potential customers will learn about the content.

The ABDs of Game Development

If there's one rule to DLC, it's this: always be DLC'ing. The gaming market is over-saturated. Release upon release -- tied with a consumer's limited time, money, and attention span -- can make a game released a month ago seem like old news fast. How does a developer compete with a constantly shifting gaming world? Add more game to your game!

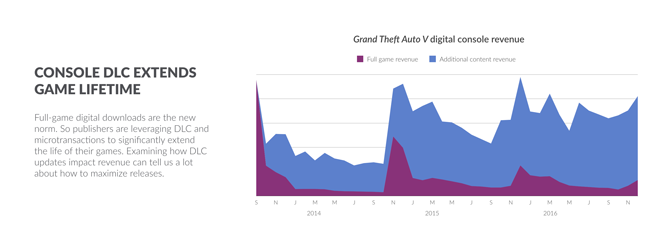

No, seriously. Consider the following statistical data showing the growth in sales of Grand Theft Auto V, in tandem with major DLC releases and micro-transactions.

Most consider DLC as minor updates meant to enhance the overall quality of the game. What DLC actually does, however, often falls short of providing users with new and exciting content. Instead, they appear as calculated bargaining chips in order to extend a title's financial lifetime. Developers therein use DLC not as in-game polish, but rather as market leverage.

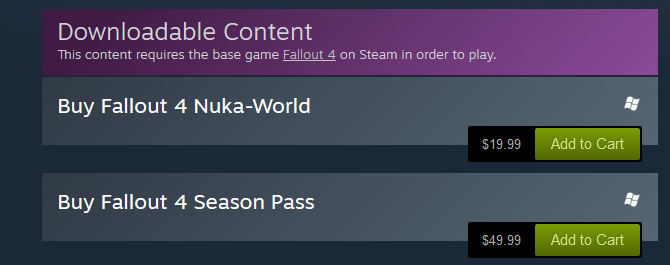

Time and time again, we see the trend of calculated DLC releases enlivening games whose five minutes of fame are all but over. Keep in mind: not all DLC suffers from this same usury. But when they do not work, they often have the potential to end game development with a final, financial squeeze. The following comes from Rolling Stone's review describing the problems with Fallout 4 and its final DLC, Nuka-World, released in 2016.

"It's SimCity syndrome: when your sandbox creation is in its final form, all you want to do is save the game and pick a disaster to befall it from the menu. Where New Vegas had an actual ending followed by an epilogue, Fallout 4 doesn't even treat you to a slideshow . . . . There is no end to Fallout 4 beyond the tipping point of terminal boredom.

Enter Nuka World. All these things you've wrought, you can destroy . . . . Becoming the Overboss of Nuka World is a final push against the waning attention span of a player who has spent too much time with Fallout 4, too much time with crafting and customization . . . . If Fallout 4 had done a better job of world-building, I think it would've been harder to lay it all to ruin.

I felt nothing but relief at the arrival of what amounts to an endgame for Fallout 4. I'd helped everyone there was to help. All that's left is to gun them all down and uninstall the game."

The similarities between this and FarmVille seem obvious. There's a habit within the game development community that attempts to expand, as much as possible, the lifetime of a game. Consider two landmark moments in gaming history: The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim and Grand Theft Auto V.

Skyrim was released in 2011. Dawnguard, Hearthfire, and Dragonborn -- DLC releases for Skyrim -- were released in 2012 and 2013. Skyrim Special Edition was released in October 2016. Likewise, Grand Theft Auto V was released on PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in 2013, PlayStation 4 and Xbox One in 2014, and Windows in 2015. That's three different platforms in two years, across multiple updated game versions, and just this month an update introduced a new game mode.

Despite being released four years ago, it's still one of the most-played games on the market.

Spin Alley

Once a DLC is released, it doesn't just lie in wait. Just as the gaming community has changed, so has gaming journalism. What was once a cluster of game reviews, guides, and descriptions has turned into a 24/7 spin cycle akin only to the political sphere.

Whole businesses base their livelihoods off gaming news, and the new advent of DLCs -- while considered by some gaming columnists as cash grabs and fixes to incomplete games -- not only offers constant new developments but constant game coverage and opinion pieces as well.

Since DLC is released in a drip-drip fashion, except for when they're genuine expansions, this means sites can cover games online for years after they're released. That also means incomplete games or games in their Early Access stages can receive even more media coverage -- meaning more advertisement and revenue opportunities -- than complete game releases. Keep in mind: while media coverage is not wholly incidental, not every patch update or DLC release is meant to feed the media spin cycle. Nevertheless, they do.

Given the modern gaming environment, developers have the genuine opportunity to create a better overall game through DLC. They should jump on every opportunity they can to create an amazing product. Incidentally or purposely, however, extra downloadable content has become a major journalistic endeavor to cover.

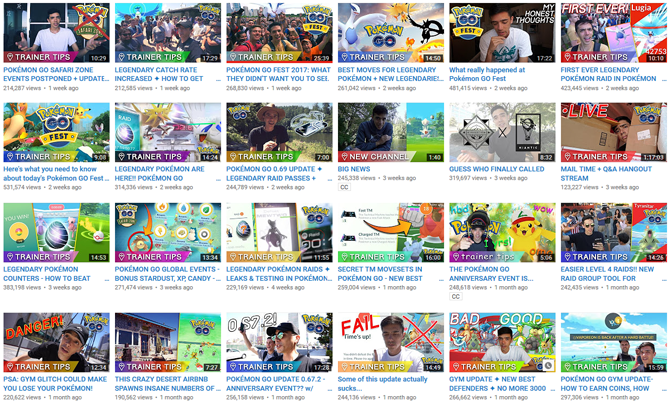

Take the YouTube channel Trainer Tips for example. Not a big fan of Pokémon Go myself (sorry), I was interested in the developing coverage around the game's recent live event. What I got from Trainer Tips is that, and a lot more.

Hundreds of thousands of views, based largely around updates. Mobile app updates -- a sort of micro-DLC -- aren't solely opportunities to add content. They're also major marketing tools, allowing attention blips in the community radar.

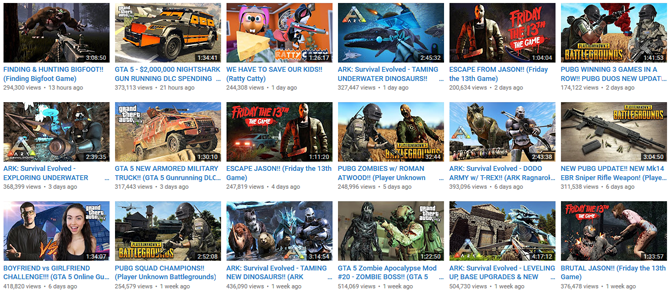

This obviously isn't exclusive for mobile apps like Pokémon Go. Popular games like PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds and ARK: Survival Evolved -- both in Early Access stages of development -- have made constant development a genuinely effective marketing tool, as is illustrated by the YouTube channel Typical Gamer. In a sense, most games played today are also in a constant state of development by necessity.

No matter the intent of the developer, releasing DLC often becomes a chance to invite consumers into the folds. Considering we've entered a new age in gaming -- the age of widespread game digitization -- wherein consumers are also reviewers, advertisers, streamers, personalities, and more, it's hard to ignore the real-world implications of DLC. Yes, they're a method by which developers can grant users more content. Overall, however, the relationship is symbiotic if not bordering on usury in some instances.

The Good, the Bad, and the Greedy

I don't want to portray all DLC as bad. There's some DLC which has contributed greatly to the overall enjoyment of games. I found out about The Witcher series through through one of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt expansions, enjoyed the two-part aspect and additional content of Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes and The Phantom Pain, and consider Goat Simulator: Waste of Space a brilliant piece of satirical work on behalf of Coffee Stain Studios.

Having spent years as a part of the gaming community, however, I know when a trend is being abused. DLC isn't a money squeeze, just as micro-transactions are anything but micro.

We're talking millions of dollars in revenue over relatively short periods of time. That's a money flood. And the practice of paid DLC -- which find their inception in casual and mobile gaming -- have all but solidified their place within gaming culture.

The Repercussions of Constant Content

There are two cardinal sins, in my opinion, which DLC is directly responsible for: they allow developers to release unfinished games, and capitalize on the user's want to play a game in its entirety. These two aspects work in tandem. Sure, I could have a great time in Fallout 4 without the Nuka-World DLC. On the other hand, do developers really suspect users will be content with an incomplete game?

Yes, paid DLC will allow users to access new content -- the product of a developer's continued hard work. Yet what, if anything, stops a developer from monetizing cutting room floor material and, when poorly received, defending themselves with an appeal to the free market -- i.e. "You didn't have to buy it!" What stops game developers from re-appropriating free, user-made mods as paid DLC instead of the stigmatized paid mods they actually are?

Another reason video game players become frustrated with DLC as a whole is because of its different variants. DLC very well may introduce micro-transactions to otherwise transaction-less games. Why buy a DLC when you can buy several with a season pass, which grants you all DLC released in an extended period of time at a steal of a price? Keep in mind, these are updates the player knows little about beforehand and may not even want. That's all without mentioning the obvious social implications of multiplayer DLC releases.

These are the repercussions of providing constant content to users. They will then crave the content, and there's only so much borrowing a game development studio can commit -- in terms of game modes, mechanics, development, and content -- before bordering on the farcical.

DLC, My Enemy

In the end, a few games will rise above the ranks and provide users with what they want: complete, challenging games one can enjoy over and over. Given that most blockbuster releases are franchise-based, however, developers have little else to prove. If it's not a new skin, it's a few more in-game credits to bypass the actual playing of a game.

Has the integration of DLC led to fantastic in-game advancements? Of course. Should we ignore the grand effect they've had on the gaming market because of that fact? Of course not.

As for myself, I'm more familiar with DLC than I am with recent, original game releases. Perhaps I'm only a casual gamer. Perhaps that was the point. In any case, whether you hate DLC or not, it works (at least, financially).

What do you think of DLC? Do you love it, or do you loathe it? Have you purchased micro-transactions or season passes recently? Let us know in the comments below!

Image Credit: fotokitas/Depositphotos