Modern computing revolutionized access to information for the visually impaired. If you're suffering from complete blindness or low vision, there are plenty of tools to help you access both PCs and mobile devices.

1. Social Media Photo Annotations

Facebook and Twitter both have products to help visually impaired users access photos on their social networks.

With Twitter's mobile apps, when uploading pictures with your tweet, you can enable a feature called Accessible Images and add a description (up to 420 characters) to the image. Unfortunately, it's only available on the Android and iOS apps at the moment.

It uses the existing alt text standard, which is a built-in attribute of the img HTML tag. Alt text is available when reading your feed with a screen reader or braille display.

[EMBED_VIMEO]https://player.vimeo.com/video/161532965[/EMBED_VIMEO]

Facebook also has an accessibility initiative that uses the alt text attribute, but photos are automatically captioned for you. This is done via a learning neural network that can recognize objects and backgrounds in photos, which is similar to the system that YouTube uses to recognize videos.

At the moment, Facebook's system can detect and describe about 100 concepts that cover things commonly found in photographs. In the case of a photo with trees, it can give the description of outdoor, cloud, foliage, land, and tree. For a photo of pizza on a plate, it would say pizza and food.

There's also a specific process to describing the elements. Photos are described with people first, then objects, then the setting. The minimum accuracy for concepts is 80 percent, but Facebook claims for some concepts it's closer to 99 percent.

It is currently available for English speaking users in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. As it's used more, the AI should learn new concepts and be able to caption even more photos. The AI actually recognizes many more objects already, but it has been limited to those it can predict with more than 80 percent accuracy.

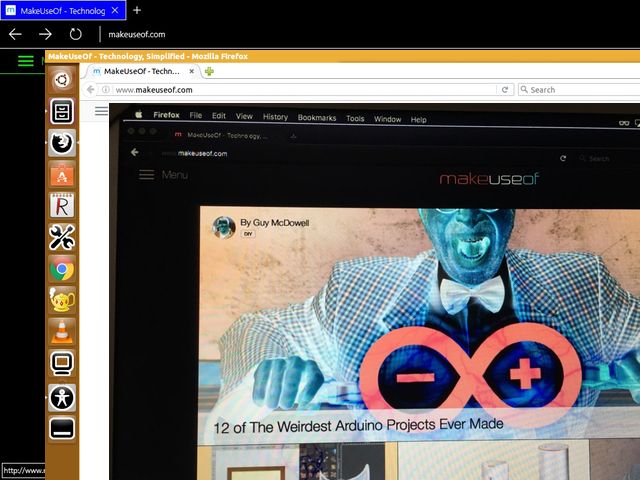

2. Screen Reader Software

Screen readers date back to the command-line era of computers, and while the technology is more complex now, the concept is the same: the software reads on-screen elements and translates them to voice so visually impaired users can interact with them.

These apps work by creating a model of what's being displayed on screen and interpreting them as text. More modern implementations use built-in APIs offered by operating systems. On mobile, screen readers have tight system integrations -- especially iOS where accessibility is a tentpole feature of the operating system.

These APIs allow for developers to add content descriptions to interface elements. For example, the Save As menu might have an attribute that lets the screen reader detect and read it out: "Menu, Save As". Each interface element's read-out would be defined by the app's developer.

Microsoft has Narrator on Windows, and while it does work, it's basic. Windows recommends that users install something more advanced for full-time use, such as the commercial alternative JAWS. However, with a bit of research, you can find free options such as NVAccess.

Apple has a more aggressive approach to accessibility across their platforms. VoiceOver is built into OS X and iOS, and features a library of multi-touch gestures for enhanced navigation. It uses the Alex voice on OS X and the default Siri voice on iOS to read elements.

There several options for Linux, but Ocra is one of the better ones (and it's developed by the GNOME Project). The project is actively looking for help to make Linux more accessible. Firefox and Chrome both have screen reader plugins to help navigate the web, too.

3. Braille Displays

Refreshable Braille displays can act as both a display and input device for visually impaired users. There is a row of "letters" that run across the bottom. The characters are a series of pins that pop up to create the braille letters. This is used in conjunction with a screen reader.

Braille readers are the only way that users that are deafblind can interact with a computer.

Readers vary from 40 to 80 characters. The American Foundation for The Blind advises that 40-character displays should be sufficient for most users, but they also say that if you're doing programming or customer service, you may want one of the larger displays.

Many braille displays have a built-in Perkins keyboard, which is a keyboard dedicated to typing braille. It has six keys for input, each corresponds to one of the six dots in braille characters. There are also some that have a QWERTY keyboard with some additional keys dedicated to navigation.

This interface allows for some braille screen readers to act as standalone note-takers. In these cases, the braille interface can be used to navigate the saved text. It should be noted that braille readers are expensive, usually over $2000.

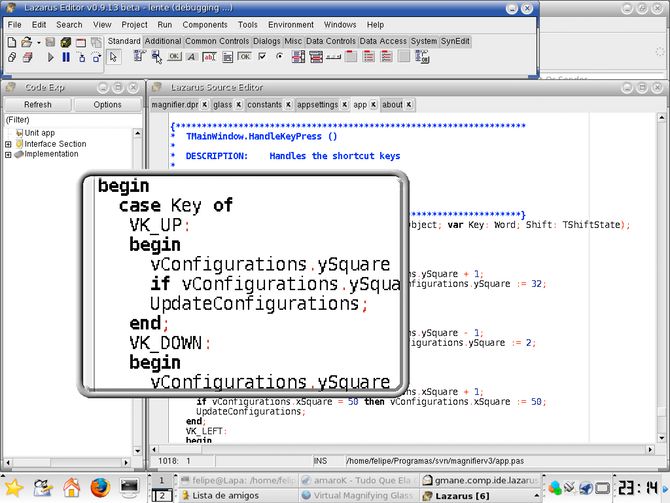

4. Screen Magnifier Software

Screen magnifiers help people who have low vision and need to strain their eyes to read small text. These programs zoom in on an area of a screen in detail, enlarging both text and images. The zoom depends on your configuration.

In some cases the entire screen zooms in to the focus point, moving some of the detail off screen. The system UI is still set to its native resolution and the elements are drawn at normal size. This makes screen magnification different from setting a monitor to a lower resolution, or even setting the system font to a larger size.

Many screen readers have a secondary mode that places a window on the screen that acts as a magnifier. It can either float around the screen enlarging as it goes, or can be pinned in one spot on the screen and follow the mouse.

There are additional options that help non-blind users with visual impairments. Inverted colors puts white text on a black background, resembling a photo negative for more complex color. Colorblind users can enable grayscale for easier distinction between color values.

Screen magnifiers are built into all major operating systems. These have basic settings that allow you to use any of the above configurations. However, there are still some other commercial and open source options you can explore.

5. Vinux for Linux Users

Vinux [Broken URL Removed] is a Linux distro that combines these technologies for an easy-to-set-up accessible computer. Released by the UK Vision Strategy, the distro is an Ubuntu variant.

What Vinux provides is a pre-configured accessible environment. This makes it much easier to set up and configure a new PC for a visually impaired user than existing Linux distros.

One of the more unique features is a call for help built into the Linux command line. As long as you have network access, you can always ask for assistance from the Vinux team. It uses their IRC channel and email to send the request, so you can get assistance with your system.

The screen reader and other accessibility features are built into most distros. What sets Vinux apart is that they are enabled by default during the install. With a default accessible installer, it's an out of the box solution for visually impaired users.

Accessibility: Complex But Necessary

The technology of accessibility for visually impaired users is a complex ecosystem. What's refreshing about the last few years is seeing how many of these technologies are built right into operating systems now.

Braille displays are still really expensive. However, the rest of these technologies can be used on vanilla hardware. It doesn't require any extra money to make a smartphone or modern laptop accessible to the visually impaired. Third-party screen readers and magnifiers can add features, but are no longer necessary for basic use.

Have you ever used accessible technology? If you have, what do you think still needs to be improved?

Image Credits: Sekelsenmat via Wikimedia, edwardolive via Shutterstock, bikeriderlondon via Shutterstock