Unlike Microsoft Windows and Apple macOS, Linux isn’t merely an operating system that can power your computer. Linux is also an approach to developing software: out in the open and freely available to all. But considering how much time and effort goes into developing Linux, a question has come up time and again for various organizations. How do we pay for all of this?

This question then gets asked of you. Should you pay for Linux, and what ways would you be willing to consider?

How Linux Is Currently Paid For

There technically isn’t a single operating system known as Linux. Linux is a kernel, the part of your system that enables your computer hardware to communicate with what you see on screen.

There is an entire ecosystem of free and open-source software that gets bundled together to create a functional desktop operating system. When someone, or an organization, bundles this software together and makes it available to others, the end result is known as a Linux distribution, or “distro” for short.

When most of us install Linux, we don’t pay anyone anything. We go to a Linux distro’s website, download the image file, burn it to a USB stick, and use that to replace or supplement the operating system that came preinstalled on our computer.

It’s difficult to charge people outright for a Linux distro or open-source software in general. Since anyone is able to view, edit, and redistribute the code, that means everyone has the freedom to make a free (as in cost) alternative to the software that you’re trying to sell.

But there is still a ton of money floating around the Linux ecosystem. Here are some of the more common models some projects use to make money:

- Donations and sponsorship: Most free software projects accept donations. Quite a few mature projects exist predominantly from this form of funding. Some examples include the Linux kernel itself plus major desktop environments such as GNOME and KDE.

- Support contracts: The most proven method for a company developing exclusively free and open-source software is to charge for support contracts. This means anyone is free to install the OS, but if they need any form of help or customization, this comes at a cost. This approach is generally aimed at enterprise customers such as businesses, governments, and schools. Primarily through support contracts, Red Hat was able to become the largest open source company and the first to reach over a billion dollars in annual revenue, before becoming an IBM subsidiary.

- Pay-what-you-want: This is an approach that gained prominence with the Humble Indie Bundle, which both attracted large sums of money for developers and had the side effect of bringing various games to Linux. The elementary project has adopted this model for both elementary OS and the apps in AppCenter. While app developers aren’t exactly swimming in cash, the elementary OS team has made enough money, alongside donations, to support a full-time employee or two.

- Charging for non-Linux versions: This is a more recent method that has risen with the rise of app stores. Software available for free on Linux sometimes appears in commercial app stores with a price tag, such as paid versions of the digital painting program Krita in the Windows Store, Steam, and Epic Store.

- Hardware vendors: Some companies sell computers that come with Linux preinstalled and use part of the profits to develop their own distributions and other Linux developers. Examples include System76, Pop!_OS, and Purism with PureOS.

Many projects use a combination of these different funding options. But for most home Linux users installing Linux on their own machine, unless they opt to make a donation, there isn’t any money changing hands.

Can You Pay Directly for a Copy of Linux?

Sure, there are people that are willing to sell you a copy of a Linux distro. You can find install disks on eBay, for example. Often this is just someone unaffiliated with a project burning the installation image on a disk for you, then charging you compensation for the disk and their time.

If you find the process of creating your own installation media intimidating, this is an alternative way of getting Linux on your system. Though there is always some degree of risk and trust involved when getting software from a third party.

With the rise of cloud computing, there is also the option to pay for a virtual copy of Linux that you run remotely on someone else’s machine. These are known as virtual cloud desktops, but this is essentially paying for an installation of Linux, just not on your own hardware.

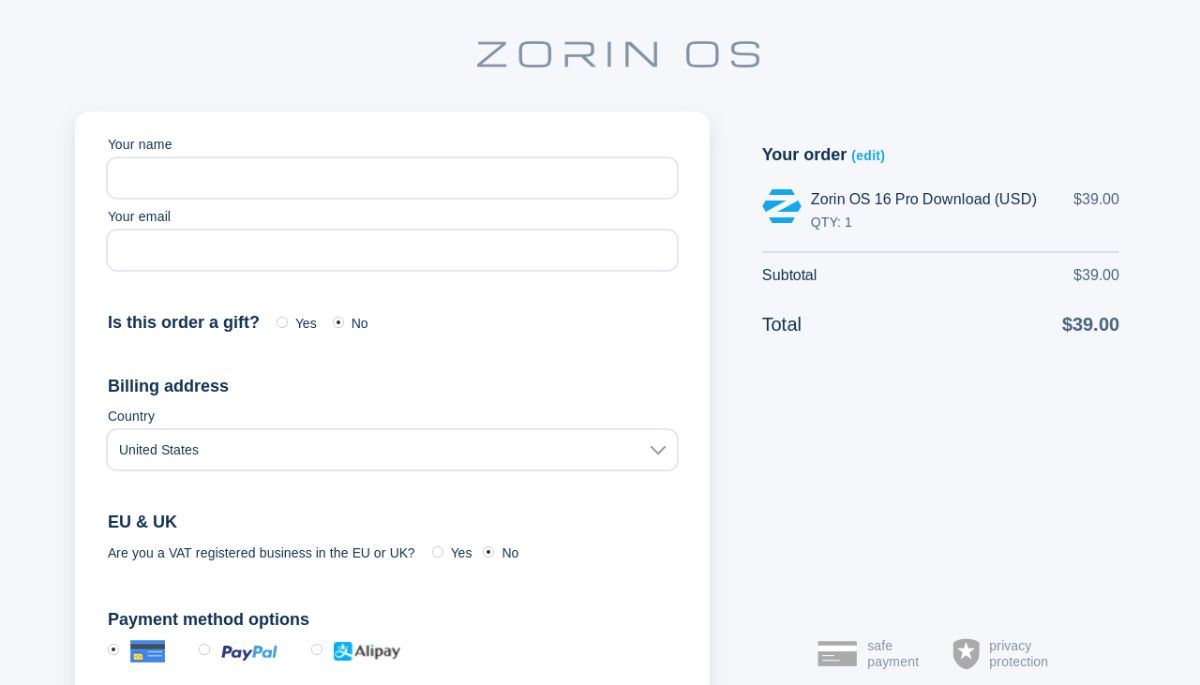

There are some Linux distros that have directly offered paid versions, such as Zorin OS. In such cases, you may get a few additional software features pre-installed (that free users can opt to install manually if they wish) or additional support.

You can also buy versions of Linux to run on Windows Subsystem for Linux, such as Fedora Remix for WSL.

The most straightforward option is perhaps the same as most people purchase copies of Windows and macOS, which is to buy a computer that comes with Linux preinstalled.

What About Linux Software?

While the overwhelming majority of programs available for Linux are free and open-source, there is a growing amount of proprietary software coming to the platform. You can find such software on Steam, Humble Bundle, and the Epic Games Store. Most of these are games. You can also purchase some programs directly from developers’ websites.

And, again, there’s also elementary’s pay-what-you-want app store, AppCenter.

Should You Pay for Linux?

The answer isn’t as straightforward as it seems. Yes, in the way most of our societies are currently structured, people need to bring in a wage or some other form of income in order to make ends meet.

People may want to contribute more to Linux but financial constraints pressure them to work for a company that will pay them to develop proprietary code instead. Creating a culture where people pay for software invites more companies to pay developers to create apps and games for Linux.

On the other hand, so much of what has made the Linux ecosystem what it is has been the way software is developed and shared freely. The expectation of payment can erode away at the idea that all of this code equally belongs to everyone.

And it could bring more proprietary software to the OS, creating an environment where most users may have a free operating system but the majority of the apps they install are as closed and privacy-invading as those found on Apple’s, Google’s, and Microsoft’s platforms.

How Much Should You Pay for Linux?

How you feel about this question may also reflect how content you are with the way things are. Do you already predominantly use free and open-source software, most of which is made exclusively for Linux? Are you left wishing you could switch to Linux, but there’s one paid proprietary app that you depend on that’s unavailable?

Do the values behind free software appeal to you, or do you simply choose Linux because you believe it offers the best experience and you want to have all the same apps you would have on other platforms? How you answer these questions may shape how, and how much, you’re willing to pay.